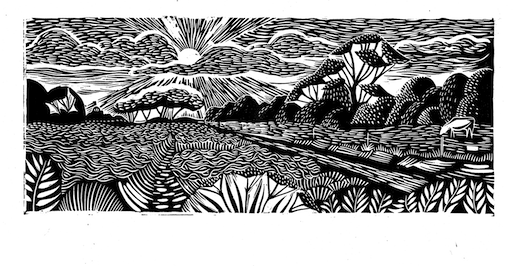

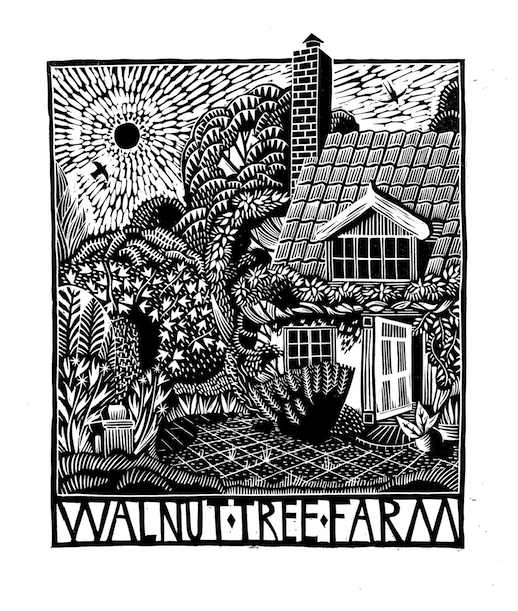

The front porch of Roger Deakin’s Walnut Tree Farm, in the blazing August sun.

The front porch of Roger Deakin’s Walnut Tree Farm, in the blazing August sun.

Words & illustrations by Nick Hayes

Part of our continuing tribute to Roger Deakin

I never knew Roger. Instead I came to the farm as many do, as a pilgrim. I’d read The Wild Places and followed the lineage, as a fledgling folkhead might trace Bob Dylan to Woody Guthrie, Robert Plant to Robert Johnston, from Macfarlane to Deakin; there’s no shortage of Robs in my starry sky. A mutual friend was the link between myself and the current owners, and I drove with him to the farm, to gorge my eyes on this new chapel of mine. The house appeared first as a white circle through the tunnel of trees, and bucking on the potholes, I felt that rare sensation that comes with penetrating a myth. Roger’s words had outlined the place, and now their subject, actualised, began to colour it in.

On my first visit I ploughed through the fields of the farm, with the goggle eyes of a spitfire spotter. Every pigeon that burst from the trees was first a peregrine, every crow an eagle, reality traipsed behind the rush. Roger’s words had prepared me for something magnificent, a Michael Mann film of the wild, the Daniel Day Lewis of paddocks. But the place was simply itself, beautiful, unadorned with adjectives, another patch of land in Suffolk. And it wasn’t disappointment I felt, but a sense of displacement, the uncanny space between the words and their object.

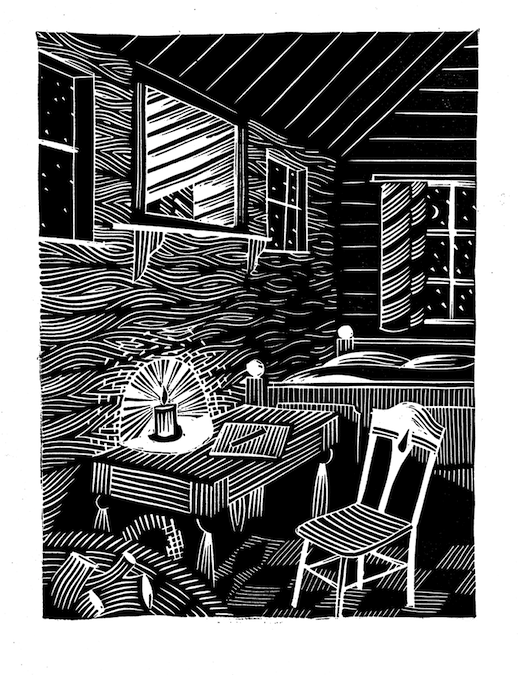

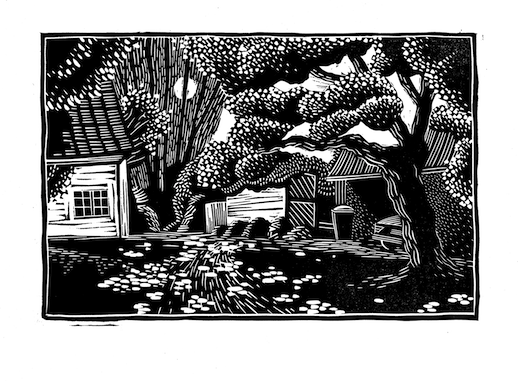

I ended up becoming friends with the family that lived there, and returned to their home often, sometimes to visit, and at longer stretches, to dogsit whilst they were away on holiday. In Autumn I would sit before the fireplace of the house, where Roger had camped in the early days before a roof, the 16th century construction that has become the hearth of a new wave of nature writing, the altar of a sect. I would pick my way through the bookshelves, a library that speaks of this new relationship in the house, Roger’s books and the family’s, alternating between poaching manuals and Geoff Dyer, Ronald Blithe and Marlon James, the silence of a late night in open country underscored by the whistling wind, the crackle of the fire and the dog lapping at his balls. In summer, I would sit outside at the caretakers table, a junkyard find of Roger’s, and draw the coppiced hazel in front of me, a spraying wooden geyser of poles and tennis ball leaves, or the bath, or the billowing jasmine that cushions the back wall.

From time to time, another pilgrim will appear, gingerly looking for the front door to knock. I will show her the moat and the ash dome, the shepherds hut and the apple trees, the icons of the books. More often than not, the moat will be smaller than she imagined; the dome more scraggly, the trees just trees. The passion conveyed through the words had magnified the reality, leaving a gap between the vision and the land. At school, you are taught to draw what you see, and not what you expect to see, which is hard enough. In time, this matures into drawing what you feel when you see it, putting both the sight and the reaction to it on paper. This becomes your fingerprint, your style, your youness. What you see, and how you see it, is what you are, peculiar to each person. And so it is, perhaps more subtly, with writing. So when I sit in the farm, and I reread waterlog, or wildwood, or the notes, my mind in the writing and my body surrounded by its subject, the gap between them is not an empty space, but something between a lens and a synapse. And that, to me, is Roger.

Nick Hayes on Caught by the River

Nick’s third graphic novel Cormorance is released by Penguin Random house in October. The prints featured can be purchased from his website shop.