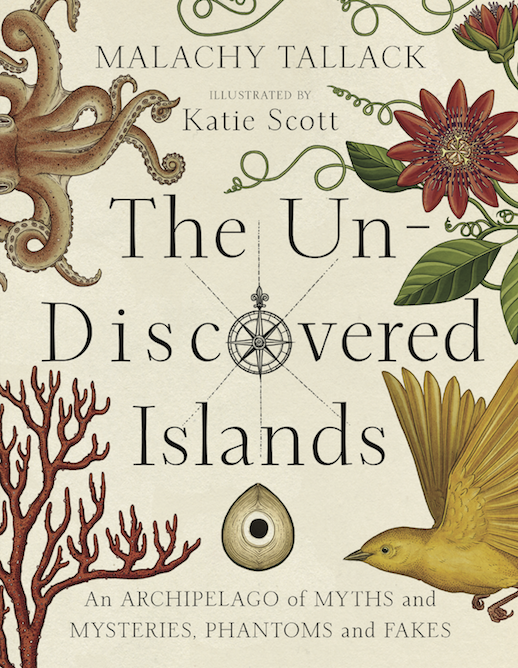

The Un-Discovered Islands by Malachy Tallack

(Birlinn, hardback, 152 pages. Out now.)

From ancient times right up to the present day, people have imagined islands. Some of these places only ever existed in myths, while others appeared on maps for hundreds of years before finally being erased. Some were strange and fabulous, while others were utterly believable. All of them reflect in some way the values of their age, and all of them have enriched the geography of the mind.

In The Un-Discovered Islands, Malachy Tallack tells the story of two dozen of these places, beginning with legendary lands, such as the Isles of the Blessed, and ending in the 21st century. The book is illustrated by Katie Scott.

Here, in the first of two extracts to be published on Caught by the River, Malachy introduces a mysterious island from the Middle East.

*

Hufaidh

At the confluence of two great rivers, the Tigris and Euphrates, there was once a wetland that covered thousands of square miles, the largest of its kind in all of Western Eurasia. This region – once part of Mesopotamia, now southern Iraq – was the birthplace of modern civilisation, and home to the Ma‘dān people, known as the Marsh Arabs. The Ma‘dān are descended from Babylonian, Sumerian and Bedouin cultures, and for five millennia their lifestyles barely changed. The way in which they lived was defined, always, by the place in which they lived.

That place was one of shallow lagoons, gangling bulrushes and low floodplains. It was a strange world, where buffalos waded among the reeds and pelicans flocked overhead; beneath the waves swam deadly serpents. Few outsiders ever knew this place, and until the mid-twentieth century it was a mysterious, half-mythical location. Gavin Maxwell travelled to the marshes in 1956, from where he brought back Mijbil, the otter that was be at the centre of his most famous book, Ring of Bright Water. That otter was of a sub-species previously unknown to science, and today it carries his name: Lutrogale perspicillata maxwelli.

Maxwell wrote of his time in the marshes in A Reed Shaken By the Wind, and in his first encounters with the place he seemed confused about how to respond. It was both repellent and beautiful to him, like nowhere he had ever seen before. ‘It was in some ways a terrible landscape’, he wrote, ‘utterly without human sympathy, more desolate and inimical than the sea itself’. And yet, two days later, that ‘terrible landscape’ had become:

‘a wonderland, and the colours had the brilliance and clarity of fine enamel. Here in the shelter of the lagoons the reeds, golden as farmyard straw in the sunshine, towered out of water that was beetle-wing blue in the lee of the islands or ruffled where the wind found passage between them to the full deep green of an uncut emerald.’

The people of this region lived with what their home provided. The water buffalo were not eaten, but their milk was drunk and their dung used as fuel and as cement. The Ma‘dān fished with spears, kept birds to eat, and in the saturated earth they cultivated rice. The reeds that grew there in abundance were tall and strong enough to be used for making boats and building houses. From inside, the great halls they constructed – mudhifs – looked like the hollowed interior of a whale. Tall, curved ribs of woven reeds supported a thick, thatched skin. Everything that was needed came from the water.

The Ma‘dān were Shia Muslims, and some were descendants of the prophet Mohammed himself. They believed in supernatural spirits, or jinn, that could take the form of snakes and other creatures. But they also retained elements of pre-Islamic beliefs, including the existence of a magical island somewhere out in the marshes. The explorer Wilfred Thesiger visited the Ma‘dān several times in the 1950s, living with them for many months at a time. On one of his stays, Thesiger was asked if he had ever heard of Hufaidh. He had, he said, but he wanted to know more. Waving to-wards the south-west horizon, his host told him: ‘“Hufaidh is an island somewhere over there. On it are palaces, and palm trees and gardens of pomegranates, and the buffaloes are bigger than ours. But no-one knows exactly where it is.”’

‘“Has no-one seen it?”’ Thesiger asked. ‘“They have, but anyone who sees Hufaidh is bewitched, and afterwards no-one can understand his words. By Abbas, I swear it is true. One of the Fartus saw it, years ago, when I was a child. He was looking for a buffalo and when he came back his speech was all muddled up, and we knew he had seen Hufaidh.”’

The Ma‘dān explained that anyone searching for the island would fail to find it. The jinns could make it disappear at will. But Hufaidh was real, they said. The sheiks knew of it, the government knew of it; there was no room for doubt. Like many such islands, Hufaidh existed in a region bridged between life and death. It was part paradise and part hell, both of this world and of another.

But Hufaidh is no longer of this world, for the marshes are a very different place today. The draining of the wetlands began around the time of Thesiger and Maxwell’s visits. Initially, it was on a small scale, to increase the availability of agricultural land. But as the decades passed, more irrigation channels diverted water away from the rivers, and the marshes began to shrink. It was not until the 1990s though that the damage was truly and deliberately done.

Saddam Hussein hated the Ma‘dān. As Shias, they were hostile to the Sunni authorities, and had sheltered dissidents and rebels. So when the first Gulf War ended, Saddam took terrible revenge. He diverted the flow of the Tigris and built a new canal to ensure the water would go elsewhere. The plan succeeded. Within two years, two thirds of the wetlands had dried up, and by the end of the decade ninety per cent of the marshland was gone. It was an act of devastating barbarism, a human and ecological tragedy.

Thousands of miles of southern Iraq, once home to fish, plants, birds and mammals, turned to desert. A unique ecosystem was lost. And the people who depended on that ecosystem – who were, in fact, part of it – were forced to flee. In the 1950s, there were half a million Ma‘dān in the region. Today, there are 20,000 in the whole country, and perhaps fewer than 2,000 living as they did for five millennia, in reed huts on the water.

After the second Gulf War, Saddam’s work was undone. The embankments were destroyed, and water was allowed to flow into the marshes once more. In the years since then they have grown, slowly, and they continue to grow. Some of the species that once inhabited the region have returned, though some are extinct and can never come back. The restoration of such a place is not a simple task, and some damage cannot be undone. The culture of the Ma‘dān may not be lost forever; those who remained may stay, and some who left may return. But Hufaidh – that island of palm trees and pomegranates – has gone. It has turned to sand, and scattered in the wind.

*

Find out more about the book at theundiscoveredislands.com.

Un-Discovered Islands: An evening with Malachy Tallack and Katie Scott takes place at Stanfords, 12-14 Long Acre, Covent Garden, London on Wednesay 19 October. More info/tickets here.