Animal Vegetable Mineral

Organising Nature: A Picture Album

(Wellcome Collection, hardback, 96 pages. Out 1 December – preorder a copy here)

Foreword by Tim Dee

Naming comes early on in human development, and came early in our species’ evolution. Language in young children commonly begins with a stab at a noun accompanied by a finger pointing at an object. Both my children said train before they said daddy.

Naming things has also long been part of the telling of our own story. In the Biblical account of creation, prior to the fall-out of the apple incident, the separation of humans from other animals needed to be asserted. The required fencing off was to be achieved by capturing all other life forms in names. Adam in the Garden, even before things went wrong with knowledge, was given an Eden project of his own: the job of naming all the animals, every beast of the field, every fowl of the air: ‘whatsoever Adam called every living creature, that was the name thereof’. ‘Naming the Animals’, a poem by the late Anthony Hecht, develops the story. Adam, new – understandably – to the game, is bewildered by his task. Shyly addressing a cow, he ventures to call it ‘Fred’.

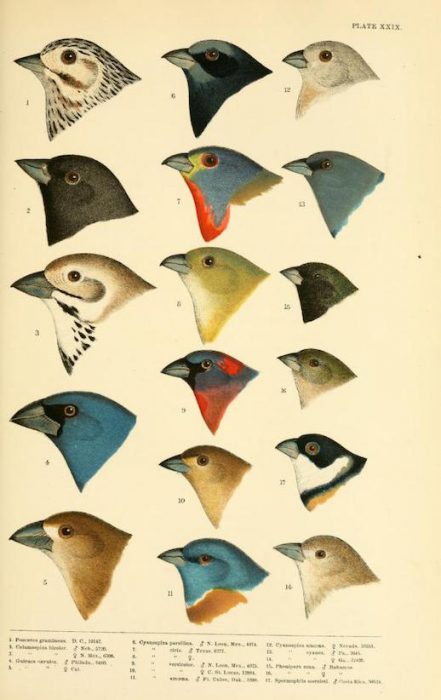

Fred the cow and Adam’s efforts underline the paradoxical effect of naming nature. Organising the world systematically with human-words, representations or man-made symbols brings wildlife closer to us. Whereas other forms of life simply exist and live, we notice what’s going on and do things to it. That might be one definition of Homo sapiens. Differentiating every hummingbird in North, Central and South America by a scientific and a common name raises each hectic blur of metallic colour into a humanly graspable existence: the birds exist and now we know them to exist. To know now that there are 340 species, where once there were thought to be just twenty, expands both biodiversity and our minds. But, in doing so, it also announces quite how diverse and profuse life is, whilst each bundle of feathers most likely cares nothing for our taxonomical attentions. Naming gives us some purchase, but it also teaches how nothing in nature is for sale, how nothing outside us – animal, vegetable or mineral – can be truly ours to have. Our nature writing is not nature’s writing. Every taxon has its own signature, and as we discover more and more, we are having to learn to read over and over again; our naming, therefore, can only be a way of putting things for us, a holding measure, the truth for now.

Go to your window in the morning, open the curtains and think how not one blackbird you might see knows that it is a blackbird; not one tree cares that it is an oak, an ash, or a lime. Not one; and yet the blackbird lives as a blackbird not as a blackcap; the ash is an ash and not an alder. We are right to tell the difference because the difference tells. And this truth is imaginatively stimulating as well as intellectually invigorating. How much better to know that instead of generic little brown jobs flying away from us there are rock pipits and water pipits and tree pipits and meadow pipits. How great a day it was when Gilbert White’s repeated walks around his parish at Selborne in Hampshire in the 1770s prompted him to realise that there wasn’t just one but three kinds of leaf-green warblers in the spring leaves. Three species, not one: chiffchaffs, willow warblers and wood warblers.

An amateur bird watcher did something similar just a couple of years ago in Gower in South Wales when, paying attention to their song, he found that he’d captured the first recorded incidence of an Iberian chiffchaff breeding in Britain. It’s a form that Gilbert White hadn’t even dreamt of, once thought to be a regional subspecies and now regarded as a full and separate species.

Careful looking lies behind this enlarging of life: the only way we know there is a rock and a water pipit is by human observers’ close attention to the reality of a bird. Our species has been doing this for a long time: one of the wonders of cave-paintings and rock-art is the specific accuracy of the depiction of animals. We might not know whether the giraffes or the bison or the wild horses are to represent a shopping list or a field note or a cloud of totemic animals for shamanic dreaming but we can immediately recognize precisely what creatures are depicted. They are named in ochre. Such diligent attention to the real and translations from it have remained a human trait ever since, throughout the history of both science and art. We might call this capture a species of love.

Not everyone would agree. Some think naming is a quasi-colonial action, a possessive anthropo-something grab after other life forms; some think that attempts to organise the order of life and to understand it to lose sight of its deeper truth and dilute its organic magic. The early 19th century poet John Clare was an extraordinary field naturalist. His poems and prose writings describe a remarkable sixty-five first bird records for his home county of Northamptonshire. Their names brightly mark all of his writing but he was hostile to the idea of scientific study: ‘I love,’ he wrote, ‘to see the nightingale in its hazel retreat and the cuckoo hiding in its solitude of oaken foliage and not to examine their carcasses in glass cases.’ Another poet, William Blake, was furious with Isaac Newton for, as he put it, unweaving the rainbow.

Let me try to persuade these doubting poets. In the last few years the DNA of the large gulls of the northern hemisphere has been scrutinised. What I grew up thinking were herring gulls and lesser black-backed gulls have been closely studied. These two species had populations all around the planet that more or less bled into one another in a continuous grey and white flight of feathers. Geographical races or subspecies were known, usually defined by having separate breeding colonies every thousand kilometres or so. But the herring gull was what I’d call any bird like it that I saw in the Mediterranean, the Black Sea, or off the west coast of Ireland, as well as on my local reservoir where I’d been birdwatching since I was a child. It was the same for the lesser black-backed gull. Then suddenly – for me at least – the two species became about ten. The herring gull survives but what were previously thought of as subspecies have been promoted to species. There are new birds to twitch: Caspian gulls and yellow-legged gulls moving north and west from their breeding grounds and American herring gulls and Azorean gulls displaced around the Atlantic. The birds themselves haven’t changed. They are as they were before the ornithological journals published papers splitting the species apart. My eyes are the same too – straining down lenses and watering in cold winds and frosty dusks. But what is now known has changed everything: the gull world has got larger, the wider world apparently therefore also. There seems to be more life on the planet. That must be a good thing.

Tim Dee on Caught by the River / on Twitter