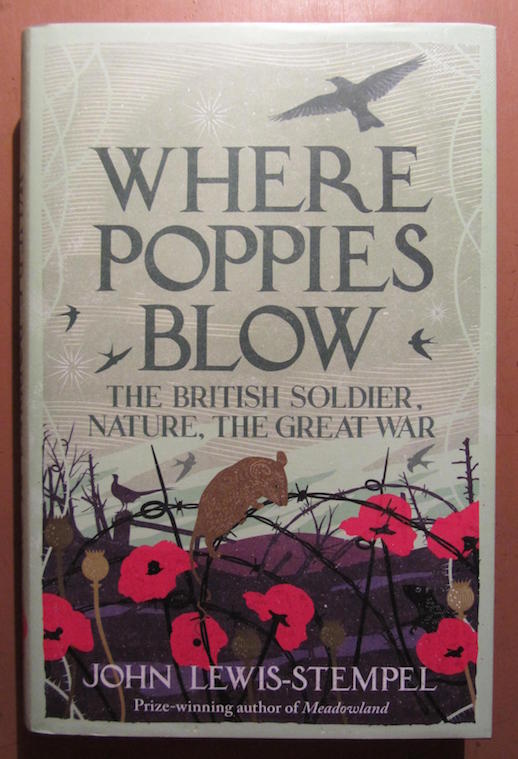

Where Poppies Blow: The British Soldier, Nature, The Great War by John Lewis-Stempel

(Orion, hardback, 400 pages. Out now.)

Review by John Andrews

“The magpies in Picardy

Are more than I can tell.

They flicker down the dusty roads

And cast a magic spell

On the men who march through Picardy,

Through Picardy to hell.”

‘Magpies in Picardy’

Lt. T.P. Cameron Wilson, Sherwood Foresters

*

Where Poppies Blow – The British Soldier, Nature, The Great War by John Lewis-Stempel marries all of the themes that have dominated his eleven books to date: soldiering, farming and more broadly, nature. The dust jacket, a jaunty clash of digitised eau de nils, purples and reds, would not look out of place on the ‘nature tables’ of high street book shops, an innocuous presence at first glance, but in the hand it is like a piece of unexploded ordnance freshly turned up by a farmer on the Somme; a deadly shell of a book packed with diary entries, lists, quotations, descriptions, addenda and statistics. Once read it is life altering, its pages shattering like pieces of shrapnel in the consciousness. Lewis-Stempel makes it clear – in 1914 men did not go to fight solely for King, they also went for country:

Whether from countryside or city, love of nature was the British condition, which manifested itself in everything from the national hobby of gardening to the folk-influenced music of classical composers such as George Butterworth and Ralph Vaughan Williams. The British led the world in the keeping of pets, animal welfare legislation and a regard for birds so marked by 1910 that Punch declared their feeding to be a national pastime, with the dockers and clerks of London included….. the people of Britain in 1914 were connected to nature wherever they dwelt. Nature was not ‘other’, separate, a thing apart.

And like nature and man in 1914, Where Poppies Blow is not a book apart. It is woven into Lewis-Stempel’s canon of work as much as it is woven into this. There is a passage in The Running Hare, his previous book, published last year to huge acclaim, that seems umbilically linked to the many that appear as soldiers’ testimonies in Where Poppies Blow. It describes a deadly collision of animal will and man-made machine:

It’s terrifying being on the balcony; it’s like being on the tiny bridge of a battleship as it pounds through waves. The balcony, with its two low, pathetic rails, is perched about the cutters, so one always feels as if one is falling on to them, particularly when the combine hits a ridge and pitches forward. The pandemonium noise, the perpetual whirlwind of straw fragments and earth. Above the cacophony, Olly shouts, ‘Do you want a go?’ I can’t really hear the words only follow the outline of his lips, now he has taken the Wild West handkerchief away from his mouth. He’s wearing the Second World War fighter-pilot goggles, found in a second-hand shop in Tenbury Wells. I slip into the seat; I’ve got sunglasses on as protection. Fighter-pilot goggles or Polaroids – such is ‘safety equipment’ in the 1970’s. I can barely hold the 575 on the line, but peer pressure is the devil’s whip, and I have to keep going to the end of the field at least. The field is long, longer than any prairie. My leg trembles with the pain of keeping the accelerator down. And why don’t animals move out of the way? A rabbit is flung up and back down into the blades, throwing a bouquet of scarlet against the artificial thundercloud. After one run down the Canadian vastness, Olly takes over again, so at least I am not driving when it happens. The terriers have come up with us, because there is nothing they like better than to chase the rats bolting out of the wheat. One grey rat decides to do a scurrying U-turn, back towards the blades. And Bella the tan-and-white terrier is right on its scaly tail. There’s a frantic shout, from me, from Olly, ‘Bella!’ But Bella never hears, not above that industrial din. Her head is cut off at the neck, and flies up towards us, her eyes wide in surprise. I remember being sick. I remember Olly banging on the rail in despair. Bella is my cousin Aly’s dog: someone will have to tell her when we return to the farm.

At first it is as if there is no narrative to follow in Where Poppies Blow, there is no map, there are no orders. But it is all the more poignant and apt for this, as this was the experience of so many men when they arrived at the Front. Words on the page explode in an endless percussion. How else does Lewis-Stempel even begin to encapsulate the life of those in ‘the Colony’, that swathe of land occupied by the Allies in the First War bordered by the 450 mile line? He handles it as he did his 575, slowly forcing his hand against the sheer weight of material that tells of an existence unimaginable had it not been described for us by those who were there: dark skies where masses of swallows feed on corpse flies, creeping dawns where skylarks usher in the daily shelling known as ‘The Daily Hate’ and empty dusks where nightingales usher it out, a world turned upside down, occupied by an army bred on folklore who saw the devil in the magpie and the friend in the horse. As you turn each page the book transmogrifies into a colony of its own description as its voices, all now belonging to those long dead, take you through a demi-zone summed up by one soldier as ‘Ratavia’ – a place where ‘Men die and rats increase’. An underground billet where all that greets a new arrival is a damp bed occupied by rats fighting over the severed hand of its former occupant, deep, deep in a burrow dug by soldiers, who, stripped to the waist, unknowingly create new words for the English language by candlelight: to ‘chat’ being a description of the neighbourly conversation that soldiers indulged in whilst carrying out the nightly duty of burning and singeing lice – or ‘chats’ as they were known – out of the seams of their clothes. Only 4.9% of the men in the British Army were louse free. Lice sent men mad and carried ‘Trench Mouth’ and ‘Trench Fever’. One of Trench Fever’s most famous victims was the 24 year old 2nd Lieutenant J.R.R. Tolkien, a signalling officer with the 11/ Lancashire Fusiliers, who was hospitalised on the 27th October 1916 at Le Touquet. There, his fever raged over the pages of the book he started to write as he recuperated, which would become Lord of the Rings: ‘They lie in all the pools, pale faces, deep deep under the dark water. I saw them: grim faces and evil and noble faces and sad. Many faces proud and fair and weeds in their silver hair’.

All the while you tell yourself that this world of pools and pale faces could only be a fiction, a place apart, left long behind. All its participants dead, yet the nations that fought the Great War still co-exist in a world uneasy and obsessed by borders. There is irony in that pesticides, one of the aspects of modern farming that Lewis-Stempel rages against in The Running Hare (‘Bayer has an arsenal of chemical weapons for weed-cleansing’), were developed by a pharmaceutical industry that grew out of the work carried out at the German Research Institute at Amani in Northern Tanganika. Amani Institute was founded after the Germans suffered high incidences of malaria in the First War – unable as they were to access quinine, the extract from the Cinchona Tree from which an anti-malarial drug was improvised, as the tree grew only in British occupied territory.

The British soldier grew wherever he went. Tubby Clayton’s ‘permanent garden’ at Poperinge was a popular retreat – ‘Come into the garden and forget the war’ read the sign – and over 750,000 acres were cultivated in Mesopotamia by soldiers and civilian helpers. A vegetable garden at Ruhleben P.O.W. Camp on the outskirts of Berlin was laid out using ‘poor quality pig manure, basic slag, 8 cwts. of bone meal and some potash’ early one spring, on a five acre site given to the men by the Germans. Into the soil the prisoners planted seeds obtained via letters to British Nurseries which arrived in Red Cross Parcels. ‘At peak production Ruhleben grew 33,000 lettuces and 18,000 bundles of radishes. By the end of the war the camp was more or less self-sufficient in fruit and vegetables and the diet inside the camp was superior to that outside it.’ Indeed outside Ruhleben ‘citizenry of Berlin were so ravenous that when a horse dropped dead in the streets crowds rushed to butcher it’.

The British soldier proved resourceful and resilient, but often it was animals that kept him going. Without horses the British would not have been able to fight, let alone win, the war:

In the mud, rain and terror of the trenches they supplied their human comrades with food, water and ammunition, even though they themselves were hungry and spent. Their numbers with the British Expeditionary Force in France alone rose to over 475,000 by the autumn of 1918.

Major General Jack Seely of the Canadian Cavalry Brigade said,

But one of the finest things about the English soldier of the front line was his invariable kindness and indeed his gentleness at all times to the horses. I hardly ever saw a man strike a horse in anger during all the four years of war, and again and again I have seen a man risk his life, and indeed, lose it, for the sake of his horse.

Horses were life. On occasion they also offered improbable escape, as Lieutenant Bernard Adams of 1/ Royal Welch Fusiliers wrote,

I rode, as I generally did, in a south-easterly direction, climbing at a walk one of the many roads that led out of Morlancourt towards the Bois des Tallies. When I reached the high ground I made Jim gallop along the grass-border right up to the edge of the woods. There is nothing like the exhilaration of flying along, you cannot imagine how, with the great brown animal lengthening out under you for all he is worth! I pulled him up and turned his head to the right, leaving the road and skirting the edge of the wood. At last I was alone.

Pigeons worked the skies – ‘of the 100,000 pigeons put into service by the British on the Western Front, 95% got through with their messages’. ‘Trench Pets’ were legion from a donkey called ‘Jimmy, the Sergeant’ who was born on the Somme in 1916 to ‘Squeak’ the goose who lived aboard HMS Centurion, from ‘Muriel’ the pig, mascot of the 1st Battalion Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers to ‘Poilu’ the lion, ‘pet of General Sir Tom Bridges and mascot of the 19th Division’. By far and away the majority were cats and dogs who included amongst their number ‘Prince’ who followed his master, Private James Brown of the 1/ North Staffordshires, all the way from their shared home in Hammersmith to the front at Armentieres without his master’s prior knowledge. Brown wrote to his wife, ‘I am sorry you have not found Prince and you are not likely to: He is over here with me. A man brought him to me from the front trenches. I could not believe my eyes till I got off my horse and he made a great fuss of me’. ‘Prince’ was made a coat of cut up discarded British Warms their previous owners no longer requiring them.

The deeper into the war that Stempel-Lewis takes you the more you harden to it. So much so that by the book’s conclusion, you once again start to believe in English pastoralism in a world where a universal Adelstrop is in view, a paradise beyond borders.

Capt. Philip Gosse R.A.M.C. managed a day’s fishing on the Somme, away from the cares of doctoring and sanitation: “I caught not a fish, but what did that matter? How better could a long summer’s day be spent than sitting alone among tall reeds, watching a red-tipped float even if it never bobbed? There were birds in the reed-beds; noisy; suspicious reed-warblers and chuckling sedge-warblers. Dab chicks dived close by, kingfishers hurried up and down the river on urgent business. One evidently thinking my rod a convenient resting place, perched on it for a while until unable to keep still any longer, I moved, and the gorgeous bird went off like a flash of blue. This was one of those rare days of ecstasy whose meaning remains but whose charm and mystery are difficult to convey to others.

Ultimately, the depth and power of Where Poppies Blow is impossible to convey. It eludes review, but it begs to be read, like all of Lewis-Stempel’s work, including his columns for Country Life, for which he won the Magazine Editor’s Columnist of the Year Award for 2016. The Observer said of him upon reviewing The Running Hare: ‘Lewis-Stempel’s eye for detail and the poetic imagery of sentences are reminiscent of the late, brilliant Roger Deakin’. Having read Where Poppies Blow you sense that much of Lewis-Stempel’s writing is also reminiscent of the hundreds of soldiers he mentions by name. Indeed were he writing in 1916 you sense that Lewis-Stempel would have been sending despatches to Country Life just as he is now, not from home but from hell.

*

MC John Andrews will oversee proceedings at our Horse Hospital event on Monday 27 February.