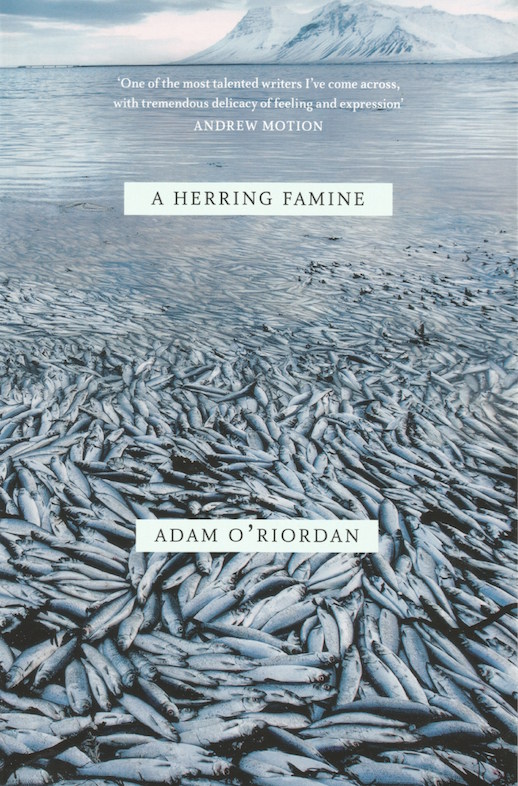

A Herring Famine by Adam O’Riordan

A Herring Famine by Adam O’Riordan

(Chatto & Windus, paperback, 80 pages. Out now and available here)

Review by Robert Selby

Many of the poems in Adam O’Riordan’s impressive debut collection, In the Flesh (2009), were inspired by, or focused upon, an image – a sepia photograph, a postcard’s beach scene, satellite imagery – and arguably its finest, Beach Huts, Milford, 1930, captured his forebears ‘mugging for the Box-Brownie’. Taking a photograph, the poem concluded, is like placing one’s hand on ‘a bible for an oath’ – an affirmation, to the future, that a certain episode from the past did indeed occur, despite all other evidence of it having been long lost.

A Herring Famine, O’Riordan’s new collection, is similarly replete with images or artifice: receiving photographs in the post from a friend (Snapshots); comparing suffragist Dorothea Beale’s Death Mask to her forbidding photograph; staring into the great face of the Romanesque fresco in Barcelona known as the Christ of Taüll; and, in Apples, searching art history for a forerunner to the vivid mental image of two boys lying dead ‘unmarked across a mass of perfect fruit’, which the poet experiences having seen a news report about their suffocation in a nitrogen-filled apple store. In the collection’s titular sequence, about his ancestors driven by barren seas to migrate from the Aberdeen fisheries to the factory floors of Manchester, O’Riordan wishes to ‘ask the pale faces / who stand arrayed // in this fading photograph’…

what it was to be so definitively delivered from a wild and known coast, to clean lines of the future

The “future” is the world’s first industrial estate, Trafford Park, and the accompanying electrified and plumbed-in Village – with its ‘churches, clinics, / clubhouse, washhouse’ – built for the workers’ welfare in that great late-Victorian/Edwardian philanthropic and municipal age. Did his uprooted forebears, O’Riordan asks, miss their former lives? Did they feel…

the skill slowly bleeding from their fingers, how to thread a net or weave a creel, gauge with wooden measures or scatter rough salt as other motions were learned, on the vastness of factory floors. If those instincts bred in them so long became suddenly redundant.

‘Redundant’ occupies a stanza of its own, neatly conveying redundancy’s loneliness as well as the guilt-tinged vacuum inhabited by those who follow, who – after the factory floors, in turn, lie fallow due to globalisation – possess and require no manual skills at all. We must dwell in the messily-entangled trivialities of modernity, in poetry – ‘the sort of thing,’ to quote Douglas Dunn, ‘a Jessie would do’ – and live hard labour, rustic romance or wartime heroism vicariously, through stories handed down. In At Sea, for instance, O’Riordan memorably relays the naval war of his paternal grandfather, who, acting captain, rammed a U-boat and watched his crew ‘fishing corpses of submariners, / interring their faces inside me.’

O’Riordan himself must make do with the less perilous dramas of romantic love; instead of altering the course of history, one must now be content to live ‘in the reflection of our falling / in the eyes of those we love’ (The Leap). The sequence Six Scenes from a Marriage is a confessional, intensely charged elegy to a marriage that did not last:

I want to write my way back into this love. To meet her newly resident in silence, in long hours of light, alone with the prayers and sandwich pastes of her aged aunt; to come to her softly as rain or wind moving through the barley.

A barley field and, later, a ‘moiling lead-lined sea’ are what one may expect as backdrops in a lament for lost love: in 2008 O’Riordan became the youngest Poet-in-Residence at the “Centre for British Romanticism”, the Wordsworth Trust. Yet the reader never loses their trust in the poet during such passages because they never read as received, mawkish or anachronistic – simply authentic. Insincerity is pleasingly, unfashionably absent throughout A Herring Famine.

In fact, the collection’s most noticeable nod to the mode goes off at half-cock: the current craze for omitting commas perceived as inessential for grammatical understanding, or all commas entirely, seems to have made O’Riordan somewhat neurotic about his, so that in some poems (The Evening Sea and The Drift for example) commas are omitted fitfully, to no strict rule, or deployed in the wrong place. O’Riordan’s poems are easefully feather-light enough that traditionally-placed commas would not inhibit their flight into our affections, where they remind us that a good poem – like a photograph – is what can salve when loss comes calling: ‘Who thought that it would come to this / that day to day, we could persist.’

*

A Herring Famine is available in the Caught by the River shop, priced £10.00