Nick Small heads underground to explore Sheffield’s urban caves

Some 1500 feet up on the top of the beautifully bleak Wadsworth Moor, rising from the kind of tussock strewn boggy hell that has tested the endurance of many a hill walker, there’s a series of impressive round stone towers. Each is about 15 feet tall, with iron barred windows through which the distant sound of rushing water competes with the howling moorland winds.

According to CBTR’s very own Richard Carter, in his book On The Moor, these are ventilation shafts for a conduit way below the surface. It was constructed in the local gritstone by John Frederick Bateman, to carry water from Widdop reservoir (elevation 320m) to Halifax treatment works, ten miles away (250m) using gravity alone, along the way, crossing the stunning Crimsworth Dean (160m) via a stone aqueduct. With water finding its own level, it is in effect a giant syphon.

Some of our most impressive feats of civil engineering were constructed by the Victorians simply to move water, whether fresh or foul, from one place to another, usually beneath the feet of unwary surface dwellers. Bateman may have been a Halifax local, but he was instrumental in bringing fresh water to cities worldwide, from Newcastle, Belfast and Glasgow, to Buenos Aries, Naples and Istanbul. London has Bazalgette’s incredible cathedrals of crap, Manchester has another Bateman project, a subterranean aqueduct from Thirlmere in the Lake District and Sheffield has what has been christened by locals, the Megatron.

Few Sheffield natives are aware of the city’s extensive network of underground rivers and storm drains, but when some caving experts from Castleton Youth Hostel in the nearby Peak district got wind of it, they decided to explore. And they did what is de-rigeur in these times, they posted videos of their exploits on social media. When the city council got wind of their low jinx, instead of censuring them, they decided to make use of their skills.

Sheffield is well positioned to announce itself as a city for outdoors lovers, being just a stone’s throw from the climbing mecca of Stanage Edge and the Peak district’s many honeypots for walkers, water lovers and cavers. The Sheffield Adventure Film Festival is a celebration of this, and one of the festival’s hottest tickets this year was a series of urban caving expeditions, led by Castleton YHA’s expert potholing scamps. The end point of the tour was a temporary screen, set up on the banks of the river, in a Victorian arched tunnel below the city’s railway station, to show a short selection of adventure films. But actually, the journey to get there was what we’d all signed up for.

Meeting at Sheffield’s hub for creative industries, The Work Station, we got togged up in caving clobber: overalls wellies and hard hats with head-torches. We clambered into an adjacent culvert, the unpromising looking Porter Brook and made our way downstream through a series of increasingly cramped tunnels. At one point, this involved a lengthy crawl through a low arched conduit, which was uncomfortable whilst trying to hold onto a DSLR with a large and expensive lens, though not as tricky as the experience for the young lass in front of me, who was carrying a guitar on her back. There was always the added jeopardy of tipping into the brook, which was squeezed tightly into man made channels, deep enough to cause a significant and embarrassing soaking, if no real peril.

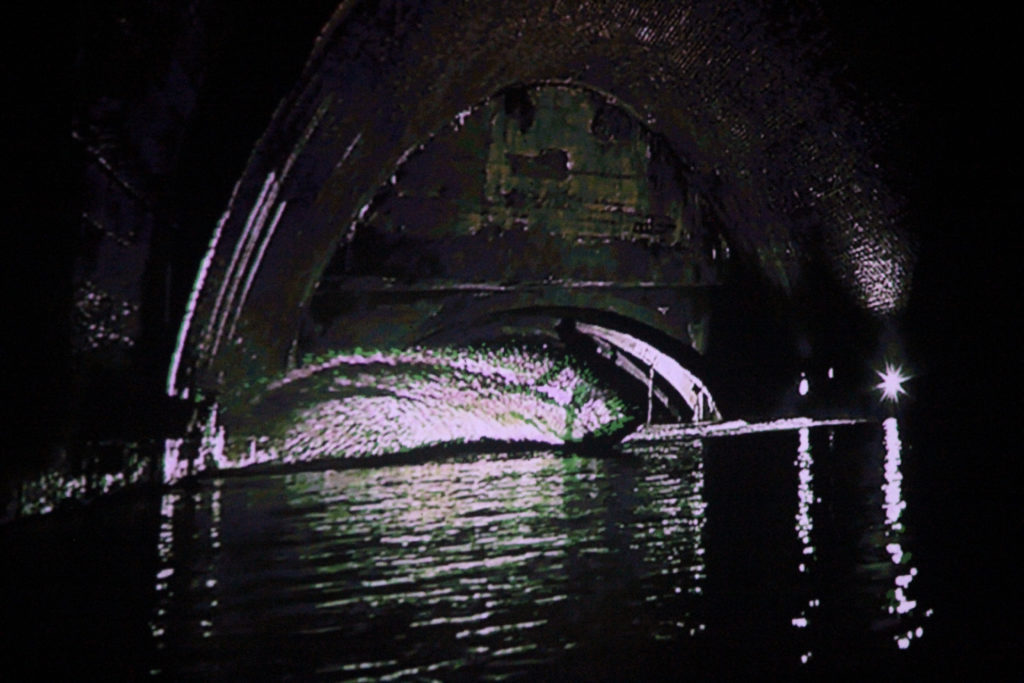

Eventually, a larger tunnel brought us to the River Sheaf (from which Sheffield gets its name). It occupies a twin arched waterway beneath the city’s main railway station. This is our introduction to what is known as The Megatron, although its main cavernous edifice was beyond the scope of our walk, and only seen in some spectacular film of underground wake boarding.

The river bed here is natural enough and more or less unchanged for hundreds of years. The tunnel was simply built of bricks and mortar around it, so that the railway station could be sited above. Evidence of this were the discarded and broken crucibles, simply dumped by 18th century metal workers on the river banks when cutlery making was still a cottage industry. This natural river bed is now a relatively safe sanctuary for the fish, fowl and other wildlife of the city, with bats roosting in the roof space and kingfishers enjoying easy pickings at Sheaf Square, where the river is open to the sky for around fifty metres.

Gathering around the screen, some 100 metres from this brief intrusion of daylight, we were treated to the songs of Esther Hyde, whose guitar managed to escape serious injury through the man made squeezes along the way. We watched films of people enjoying the great outdoors, but most of us were gazing around in wonder at the scale of the Victorians’ vision and engineering. You couldn’t help but wonder what we’d do now, if faced with the problem “how do we get a railway station and a river to share the same plot of land?” The solution would no doubt involve pre-formed concrete tube sections: effective at moving water from A to B, but not creating a space that would invite wildlife, or parties of curious urban cavers a century later.

Anyone intending to explore these urban caves for themselves should be aware that they can flood pretty rapidly, so for the unprepared and ill-informed (meteorologically speaking) they’re a potentially dangerous place to hang out.

With experienced guides, they’re places of wonder.