Read an extract from Mick Houghton’s Fried & Justified: Hits, Myths, Break-Ups and Breakdowns in the Record Business 1978-98, newly published by Faber.

I began working with ‘the other’ Paul Smith in 1989; Paul had founded his Blast First label in order to release Sonic Youth records in the UK and Europe four years earlier. The group’s wider success in the future owed much to Paul’s drive and determination, and Sonic Youth definitely broke out internationally after having first made an impact in the UK through Blast First. Yet by the end the year, Sonic Youth and Blast First’s other key US groups – Dinosaur Jr and the Butthole Surfers – had all flown the coup.

So it was no wonder that come the 1990s Paul set about decelerating and diversifying Blast First. It became weirder and less brash guitar-dominated and more of an umbrella for a series of events and projects that cast Paul in a similar mold to Bill Drummond with a belief that anything is achievable. I tagged along for the ride from time to time.

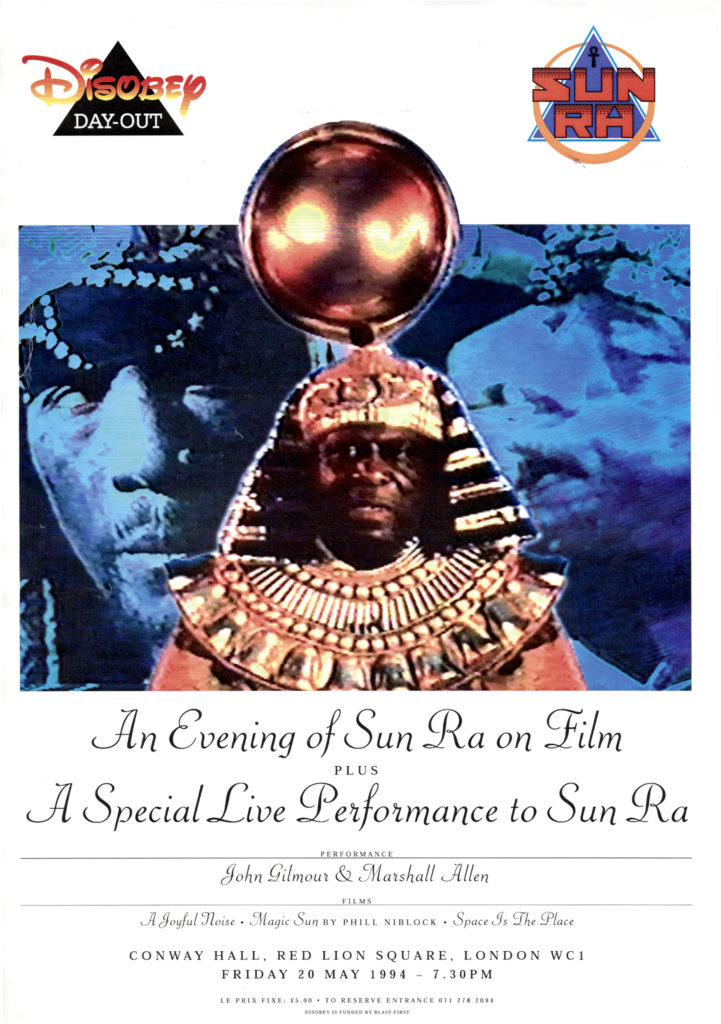

Paul brought Sun Ra’s Arkestra to the UK in 1990 for two magical visits and a few years later he started up a unique multimedia club night called Disobey, which ran for a year during 1994/5, usually operating in the cramped upstairs bar at the Garage in Islington. It was the antithesis of an ‘arts’ venue, where Disobey managed to overcome any elitism and pretentiousness with series of disparate events, presenting tenor sax extremist Charles Gayle, an unbearable barrage of noise by Caspar Brötzmann, readings by Iain Sinclair and Kathy Acker, Finnish techno duo Pan Sonic and a talk by Cynthia Plaster Caster. Paul also brought author and Merry Prankster Ken Kesey over to the UK for a Disobey Day Out at London’s Conway Hall.

In August 1998, he brought Kesey and his amiable psychedelic sidekick Ken Babbs back, this time selling out two nights at the Barbican, plus talks in Dublin and at the Edinburgh Festival. The dates heralded the launch of another ambitious Paul Smith undertaking, a spoken-word label called King Mob. At least seven years in the planning, King Mob’s manifesto was: ‘Music begone! All music is dead, reduced to nothing more than competing background noise. Only the human voice can save you.’ It was a far cry from the oleaginous Martin Jarvis reading the classics.

King Mob’s aim was to release cult fiction read by its authors, which took a leaf out of the Beatles’ book. Apple Records had brought Kesey to London in 1969 to oversee a project involving authors reading their own work on a series of albums that Paul McCartney christened Paperback Writings. Unlike Apple, King Mob did actually release a batch of titles, which comprised Kesey and Babbs’s notorious Acid Test recordings; urban portraits by Charles Bukowski, recorded in 1968; cult writer Stewart Home’s Pure Mania; Iain Sinclair’s London riverside fable Downriver – with sound interludes courtesy of Bruce Gilbert of Wire; Ken Campbell’s Wol Wantok, a crazy, instantly learnable new language; and a proto-rap oration by the Black Panthers’ Bobby Seale.

Kesey’s visit overshadowed rather than heralded the launch of King Mob. The advance press was mountainous, although I didn’t enjoy ferrying Kesey round to do interviews. In between them he was grumpy and unappreciative. He was a hard man to warm to, but he knew how to turn on the charm when the tapes were rolling.

He turned it on for the shows too. Clad in a Stars and Stripes waistcoat, and underneath a Stetson, Kesey was a compelling, mesmerising performer. He told entertaining and touching stories about meeting the Beatles, delivered an elegy for John Lennon and gave a lengthy account of three teenage dropouts who made a pilgrimage to his Oregon farm (where the Pranksters’ original magic bus was rusting away) during the week of Lennon’s death. He even carried off a twenty-minute hipster children’s tale about Tricker the squirrel, who gets one over on an angry bear called Big Double. ‘Are you still tripping?’ shouted somebody in the audience. ‘Are you kidding?’ came the reply, amid a torrent of laughter. One reviewer likened Kesey’s guru-like command of the crowd to Graham Chapman’s character in Life of Brian. Kesey wasn’t the Messiah, but nothing he spouted was going to shake the loyalty of those who flocked to see him.

The following year Kesey returned, this time travelling round in a newversion of the Magic Bus, with a motley crew of hippies of all ages occupying its seats. They went ‘In Search of Merlin’, performing at Cornwall’s open-air Minack Theatre on a drizzly 11 August to coincide with the solar eclipse. The bus then chugged its way to Brixton Academy. The ‘Where’s Merlin?’ pageant was the supposed highlight of a show that had sold less than a hundred and fifty advance tickets out of a four thousand capacity. The biggest cheer from an eventual five hundred onlookers came when the curtain opened to reveal the bus. Not the bus, of course, but a bus. For a while they were happy to suspend disbelief, but it was amateur hour, culminating in the laughable Arthurian pageant itself. It resembled a school Nativity play, but was nowhere near as professionally staged. Kesey, this time in a top hat, presided, but the charming man who had been so enthralling at the Barbican had become more Captain Mainwaring than Captain Trips.

Kesey was a tired-looking and often forlorn shadow of the man I’d met a year before, and once again the press build-up had been hefty. I was glad there were so few reports. I was convinced the reviews were spiked out of respect for his countercultural glory days. The tour had been overly ambitious, seriously flawed and anarchic for all the wrong reasons, but nobody wanted to dent Ken Kesey’s mythical status.

It proved to be his final UK trip. Kesey died of liver disease two years later, in November 2001.

*

Fried & Justified: Hits, Myths, Break-Ups and Breakdowns in the Record Business 1978-98 by Mick Houghton is out now, published by Faber.

Mick will be discussing the book with Teardrop Explodes member / Zoo Records founder David Balfe, and writer & critic Ben Thompson, at an event in Brighton on Monday 15 July. More info here.