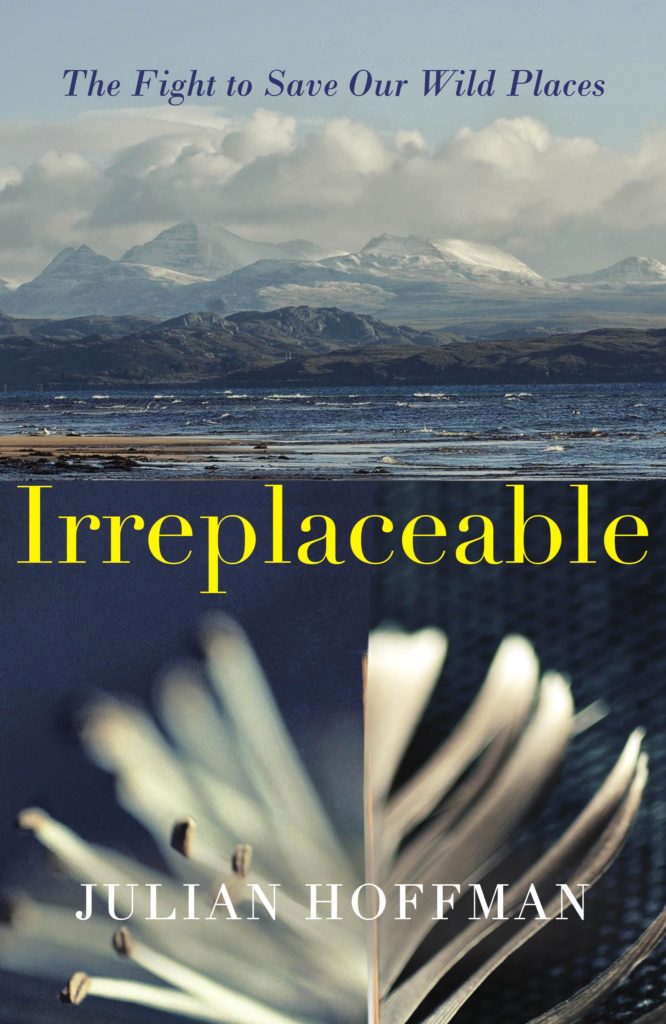

Julian Hoffman’s Irreplaceable: The Fight to Save Our Wild Places was recently published by Hamish Hamilton. Read an extract from the book’s introduction below.

A testament of minor voices can clear away any ignorance of a place, can inform us of its special qualities.

~ Barry Lopez, ‘The American Geographies’

Although the young man playing crazy golf wore shorts, the day was sharp and shivery on the pier. Glassy March light slid off the waves and broke into bright shards. Further out to sea, panels of dark grey rain had been hoisted against the horizon, blotting it from view. The arms of the Ferris wheel spun slowly on the promenade and the air plumed with the unmistakeable tang of the British seaside, a fusion of salt water, fish and chips, and candy floss. I walked Brighton’s Palace Pier with the late-winter crowds, day-trippers and city residents mingling together to ride the rollercoaster and dodgems, dropping coins into the slot machines in the giddily lit amusement arcade, or to walk the length of the pier and back and feel the crisp, bracing wind against skin. Food shacks did brisk business, steady queues forming at Doughlicious Doughnuts, Hot Dog Hut and Moo-Moos, whose staff coned a dazzling rainbow of scooped ice creams, still popular in the biting cold. Loudspeakers garlanded the entire length of the pier; a middle-aged couple, already hand-in-hand and laughing at some-thing one of them had just said, rocked back on their heels and tapped out a two-step when Van Morrison’s ‘Brown-eyed Girl’ rang out across the sea.

It was a few minutes to five when I chose a spot on the sunset side of the amusement arcade, staring across the water at the sad remains of the fire-destroyed West Pier and the skeletal crown of its sinking pavilion. A few other people had gathered alongside me, including a man setting up a camera and tripod. ‘Photography is just my hobby,’ he said, screwing in a long lens. ‘I’m a financial investigator by day.’ Another man wheeled his invalid father to the railings, the older man wrapped in a beige overcoat and brown woollen scarf, their wives jointly tucking a navy-blue blanket down the sides of the wheelchair. And then, at precisely 5.03 p.m., as hands were being rubbed together along the pier to kindle a little warmth, the performance commenced.

Eight starlings hustled overhead like a fan of thrown darts, roving the glimmering grey sea between piers. A minute later and another twelve had joined them, followed by countless small additions and accretions over the next quarter of an hour, so numerous that I could no longer keep track of their source. It was as if they were simply materializing from within the growing assembly in an endless process of self-replication, or being sieved unseen from the sea. As if in response to the swirling birds, several hundred of them now fusing into a mass of rippling black felt, dark clouds billowed westwards, pressing the last of the winter light into a thin shining seam between horizon and sky. And from that sliver of crushed sun, the rays flared outwards and over the sea, unwinding like a trawler’s net and raining light on the wheeling birds.

Murmuration is the word given to these grand assemblies of starlings, descended from the Latin murmur, meaning to surge, though a friend of mine offered a lexical variation. ‘It sounds like a compendium of murmur and admiration,’ he’d once written. Which seemed about right to me – and I suspect to the many others gathered that evening on the pier. Not merely the ones who’d arrived especially for this regular winter event, but for those unknowing visitors pulled in by the sheer unexpected magic of it all. For the murmuration was difficult to ignore: it trembled off the coast as if the dancing images of a cinema reel were being projected onto the air itself.

Over a thousand birds had now coalesced into a single aerial mass, each flickering and feinting of a life form mimicked by its neighbour, the process repeated over and over throughout the gathering. Whenever I tried to follow the trajectory of a single starling, to glimpse individuality amidst union, my eyes lost focus within seconds, tugged inside the dense, darkly incandescent pulse of the cauldron. Together they shape-shifted into mystifying forms as evening fell around us – the black coil of a sinuous snake at sea, a bowl set spinning through salt air, a wine glass brimming with the last of the drained light. No sooner had a shape been perceived than it had already morphed into something radically unrelated, as if a sequence of ethereal phantoms, fugitive and fantastic in their unfolding. The starlings spiralled, ribboned and wavered, a vast tremulous cloud of intelligence, each curvature and warp in the air a response to their dynamic but precise volatility. And few movements seemed beyond their reach. Often congregating in such bewildering numbers to better survive the incisive attack of a predator, starlings have perfected the artful synchronicity of grace under pressure. A battle shield of weaving wings against the piercing talons of a peregrine.

The murmuration had a profound effect along the length of the pier. Two girls abandoned the selfies they were taking in front of the games arcade, standing side by side instead and re-angling their phones so that the camera lens faced out to sea. A woman, middle-aged and wrapped warm in a burgundy scarf, simply said Wow in the midst of it all, entirely transported by the spectacle. And the man in the wheelchair smiled weakly as he stared at the display. At one point the flock fractured into two distinct entities, each scrolling to the edge of the sea-stage before turning, floating inwards out of a desire to re-form. When they met in the middle, jointly arching upwards like tree boughs shaken free of snow, each flock dissolved into the other. They passed through as if ghosts instead of matter, without hint of contact or collision, their passage as perfectly executed as choreographed dancers crisscrossing through one another’s lines. A group of couples in their late teens, done up for a Friday night at the pub once the pier closed, had got caught up in the sway of the starlings, excitedly flipping phones from their pockets, turning them sideways to film the unexpected dance in the air around them.

Starling murmurations are scientifically known as scale-free correlations, formations that most closely resemble criticality in their characteristics, this being the exact point at which systems stand on the brink of a radical transformation, such as water becoming ice or snow turning to avalanche. Each and every starling in the shifting body of birds is constantly moving in relation to its closest companions, regardless of the flock’s size. According to an Italian study, orientation and velocity are precisely calibrated to a starling’s seven nearest neighbours, so that the orchestral swing of a murmuration is governed by tiny deviations almost instantaneously transmitted by way of a ripple effect through the entire assembly. How starlings are capable of such synchronous correlations remains unknown, but there on the pier it was uncomplicated wonder that encompassed the experience, calling so many of us to the railings to dwell for a few minutes within its embrace, taking leave of other things in order to nourish the human need for mystery, beauty and wild creatures.

‘Mum, look at this side!’ cried a young boy, trampolining with joy on the wooden boards. ‘They’re over here as well!’ And so we all followed him to the other side, as though the pier were in fact a tilting ship in a storm, its passengers sliding back and forth across the deck with the swell. The starlings were incoming now, their sky-vessel moored for the night. The murmuration began to unravel and fray as evening gradually darkened, each buoyant weave falling towards the sea before being drawn down in long ribbons into the structure of the pier itself, as if sucked inside by a vacuum cleaner. Within seconds the dreamscape of birds had vanished from the air.

I began to walk back off the pier, fizzingly aware of the momentous, transforming effect the starlings had had on us all. From beneath my feet I could hear a chittering chorus, the ‘testament of minor voices’ released from their murmuration until tomorrow. Roosting on the iron struts of the pier, beneath the weight of slot machines, doughnut vendors and fairground rides closing up for the night, hundreds and hundreds of starlings were huddled together and separated from me by only the worn wooden planking, the magic of their kind so close and living alongside us. I knelt down and peered through the gaps between the boards. There I glimpsed a blurry rustling and skittering of bodies, as those small informing voices rose through the darkling air.

*

Irreplaceable is out now in hardback, priced £18.99. Read Paul Evans’ review of the book here.

Julian Hoffman and William Atkins will be discussing themes of wildness, connection and the ecologies and cultures of place at Burley Fisher Books this coming Tuesday, 9 July. More info here.