Luke Turner reviews Mark Jenkin’s acclaimed new feature film, centred around modern life in a Cornish fishing village.

Films about people who work the land (or sea) come with the expectation of broad horizons, lingering shots of sunsets, gulls soaring over plough or boat. Bait, Mark Jenkin’s acclaimed feature film about a Cornish fishing village, has the occasional glimpse of a distant headland, but mostly it looks inward and up close – a washing up bowl containing a few dead fish, a harbour wall, fag butt in a gutter, hand in pocket, the foam atop a pint. Shot in black and white, it is resolutely not what we expect from Cornwall on screen, far from the ludicrously over-tinted palette of Poldark, or the nature documentary meets tourist board propaganda encountered in the likes of Coast.

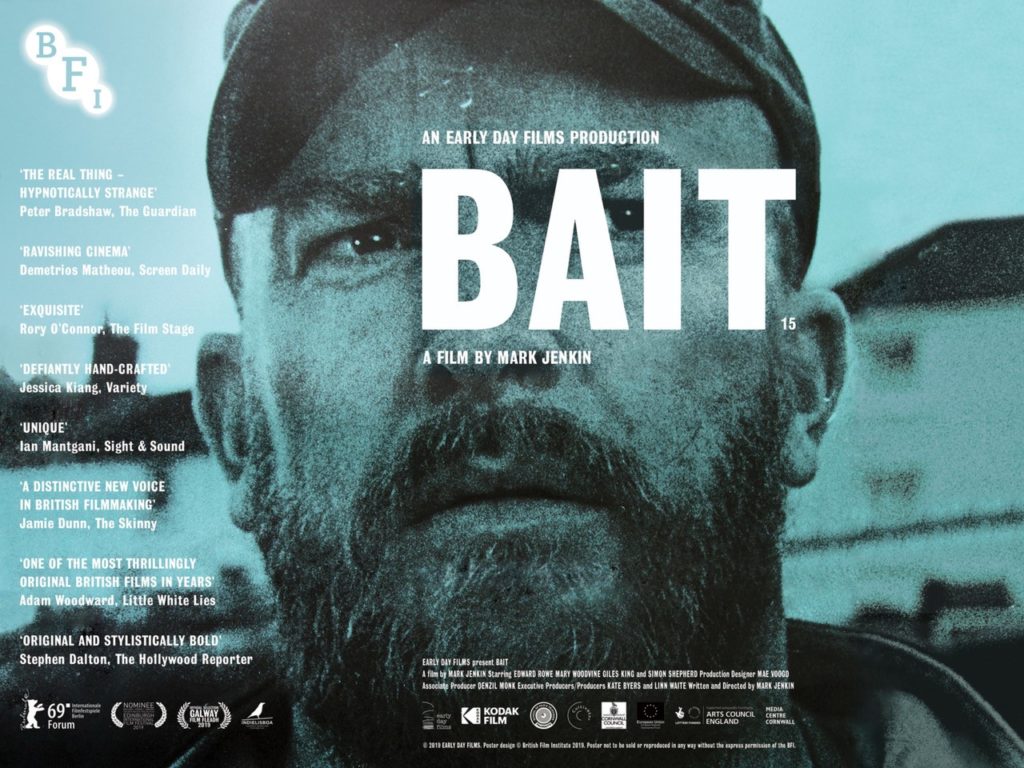

The release of Bait in 2019 is the end of a long process for Mark Jenkin, in whose imagination this film went through umpteen iterations until he shot it with a local, largely untried cast, using an ancient and temperamental 16mm Bolex camera and developing the film himself. Bait has been discussed as experimental cinema — which it is in the sense that you won’t have seen anything like it, but beware of letting the arcane equipment or film buff chat detract from a very powerful, and often darkly funny, human story.

Jenkin has spoken about the influence of Derek Jarman on his work, saying on a recent BBC Radio documentary that “one of the things I love about The Garden is Jarman’s love of the hand-made… it’s obviously lo-fi, so amateur I suppose but there’s something so human about it. It opened my eyes to how a film can be made.” That DIY spirit is strongly present throughout this remarkable film. The ‘psychedelic’ is generally thought of as being escapist, but in both Jarman’s hallucinatory dialogue with the Dungeness landscape and Jenkin’s dreamlike cut-up style, we see it becoming intensely political. Where The Garden commented on the rancid homophobia of Thatcher’s Britain, Bait articulates the tensions within a divided country where wealthy Londoners waft down to second homes in the second-poorest region of Northern Europe.

Fisherman Martin Ward (played by Edward Rowe, AKA the Kernow King) is caught between sea and land, the old world and the new. Disgusted that after the death of their father his brother Stephen is using the family boat to take stag dos on pissed-up fishing trips, Martin instead stretches nets on the beach for a meagre catch that he sells to a local pub. To him, that is more true to the family tradition than entertaining holidaymakers who’ve turned an industry into a curio. The plot, evolving over a week in late summer, explores the strained relationship between the Wards and a family of middle-class incomers who’ve bought the fishing family’s former house. They’ve filled the fridge with Prosceco and blueberries and covered the walls with fishing ephemera, a twee appropriation of the tools of his trade: “All bloody ropes and chains. Looks like a sex dungeon,” Martin Ward tells Stephen.

The tension is held in fast cuts and close-up between the faces of the protagonists, often taken from unexpected angles and suddenly shifting to cutaways. Similarly, the sound design is ominous and claustrophobic – the exaggerated thud as a box of fishing gear lands on a beach, the rattling of boat engines. Even the dialogue, dubbed in after the film was shot and during the editing process, adds to the sense of dislocation and unease. The use of film, with its flaws and imperfections (at one moment the screen fills with white fuzz – Jenkin had it hung up to develop on a spring day when the wind blew pollen into his studio) is no gimmick but gives Bait a timelessness, evoking a classic kitchen sink drama brought bang up to date.

Bait is a powerful, beautiful film about modern Britain that refuses to sentimentalise imperilled industries and the communities around them, for fisherman Martin’s intransigence is more frustrating than heroic. It understands that we all play roles defined by class and birth, all as caught as one another. I also sensed in the oppressive atmosphere that an intense dislike for outsiders can have more twisted overtones when directed at other groups who are not irritating members of the white upper middle class. Bait is provocative too. I went on holiday to Cornwall two weeks after watching it, and the lingering memory made me doubly conscious of my privilege and status as an outsider. But making the viewer or consumer feel uncomfortable in difficult times is one of the tasks of visionary art. That Mark Jenkin has made this bold and haunting film while pushing the boundaries of what can be done with a tiny budget and DIY attitude makes it a modern triumph.

*

Bait is released in cinemas UK-wide by the BFI.