Hanna Tuulikki’s new installation at Edinburgh Printmakers is a life crisis ritual for a damaged planet, says Anna Fleming.

Behind the curtain, the dance.

Dum.

Dum.

Dum.

Open the curtain. Step into the darkness.

Dum-de-dum

du

Dum-de-dum

du

Inside black space, meet the Deer Dancer.

Hanna Tuulikki’s new instillation at Edinburgh Printmakers is a life crisis ritual for a damaged planet. Tuulikki, an artist, composer and performer, combines film, dance, vocal composition, costumes, props and visual score prints to create a bold and haunting artwork.

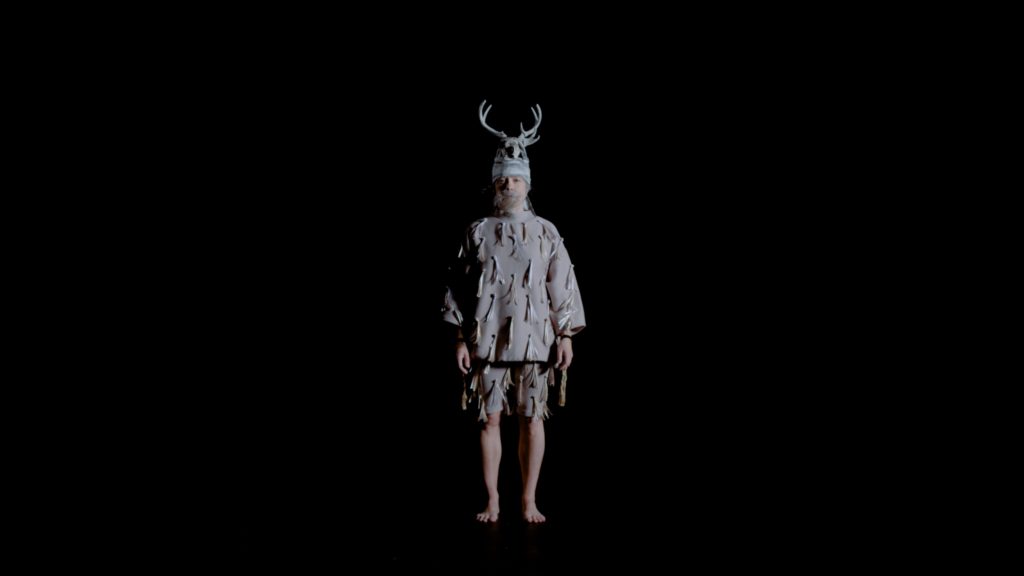

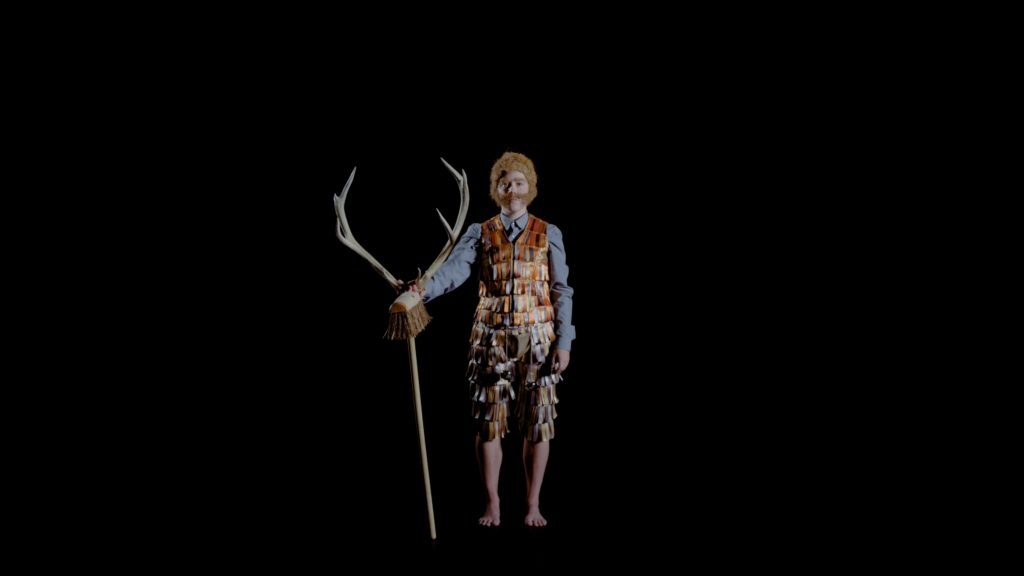

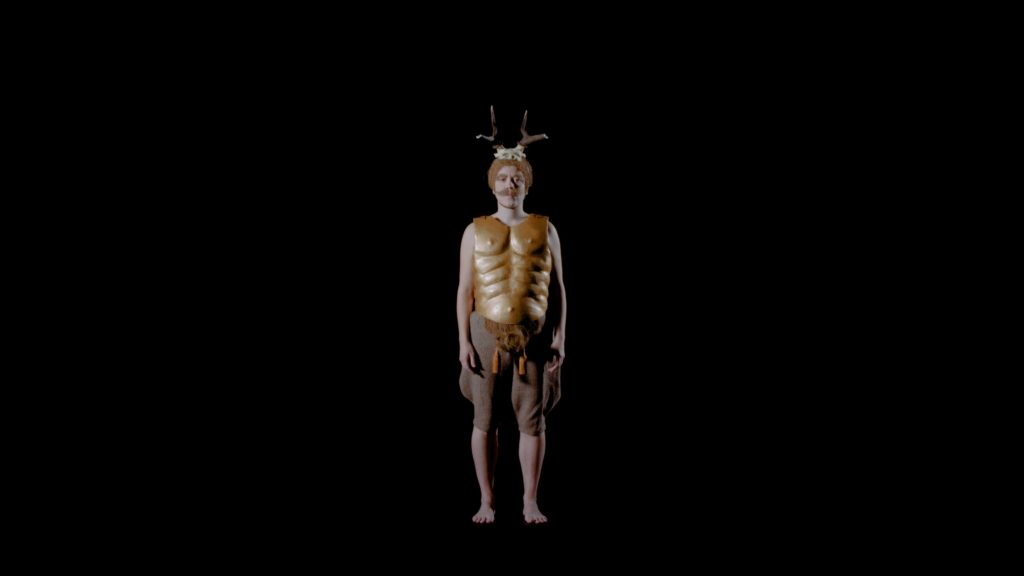

Five deer characters pace across black screens inside a dark curtained room. The stag-men face one another, dancing, gesturing, chasing, pausing. Like deer in the forest, they rapidly cut in and out of shot: now appearing; now vanishing. The Monarch, Warrior, Young Buck, Fool and Old Sage – each character is played by Tuulikki and each has his own distinctive costume, featuring sequins, cod-pieces, sporrans, deer-hide, antlers and crowns.

The stag-men hop and step, raising their arms and twisting their bodies in sequences based on three deer dances from around the world: Highland Fling of Scotland; Abbots Bromley Horn Dance from Staffordshire; Deer Dance of indigenous Yaqui from Sonora, Mexico. This pastiche of dances, coupled with the symbolic characters, elaborate costumes and gender swapping feels Shakespearian. My sympathies shift. The stag-men are strong and ridiculous; wise and timid; impressive and vulnerable. The performance edges the line between comedy and tragedy.

Deer, the work reminds us, have been important to humans across the planet. We have mimicked and mirrored deer in dance, song and story across time. Nineteen thousand years ago, humans drew reindeer with fantastic antlers on cave walls. Deer are an archetype. We portray the deer to chronicle our own histories; we embody the deer to negotiate relationships. Deer are nature and culture; past and present; human and animal.

Deer dance across space. They challenge boundaries. In Scotland, deer are a live issue at the heart of land reform debates. Who owns the land? How is it managed? What should it look like? Sporting estates profit from huge deer stocks, conserving a Victorian model of the romantic Highlands, a wilderness (or wild-deer-ness) where one can hunt the ultimate trophy: the Monarch of the Glen. Yet intensive grazing damages ecosystems. There are places with telling deer fences. On one side of the fence, nothing grows taller than your knee. On the other side, among the grass and flowers, juniper, birch, rowan, pine and willow spring up. These small trees add texture, variety and homes for different species.

But – like a wall – a fence is not always the answer. Fences can break; they restrict other wildlife. And deer move. Deer leap fences; they cross boundaries. Conflict simmers between neighbouring estates with different land management approaches. In our time of ecological crisis, we urgently need to restore damaged ecosystems. Monocultures breed mono-pests: ticks are flourishing; lymes disease is spreading.

A degraded ecosystem is more vulnerable to climate change.

How can different species co-exist?

In addressing this big environmental question, Deer Dancer widens the lens. Tuulikki suggests that the issue is not just about how we conceptualise and manage land; but also how we construct and perform gender. The work explores the limitations of heroic and hetero-normative masculinity through the five male characters. We see the Fool, struggling with his hobby-horse-deer. The hobby wants to drag him into fights; the Fool is terrified. The Sage is gentle, wise and energy giving; why doesn’t he step in and do something?

Deer Dancer challenges binary thinking. Instead of nature and culture; male and female; human and animal, the artwork suggests that perhaps it is time to soften these categories and allow for greater movement. Flux. Change.

One way into fluid thinking is through embodiment. Mimesis, or the process of becoming other, is at the heart of the piece. The dancer follows steps laid out by different cultures. The dancer paces old ways. She revives rituals that have been repeated, reworked and passed down from one dancer to the next. She inhabits different interpretations of the more-than-human. She wears multiple guises. The human is not fixed. Deer Dancer embodies many shifting imaginings of self and world.

The film plays on loop. The stag-men die and are reborn. Outside the dark screen space, the costumes hang empty, waiting, ready to be inhabited by the next dancer. This performance of crisis and renewal is at once timeless and urgent. The dance heralds a transition. The ritual will be repeated.

*

Deer Dancer is at Edinburgh Printmakers until 6 October 2019. More information here.