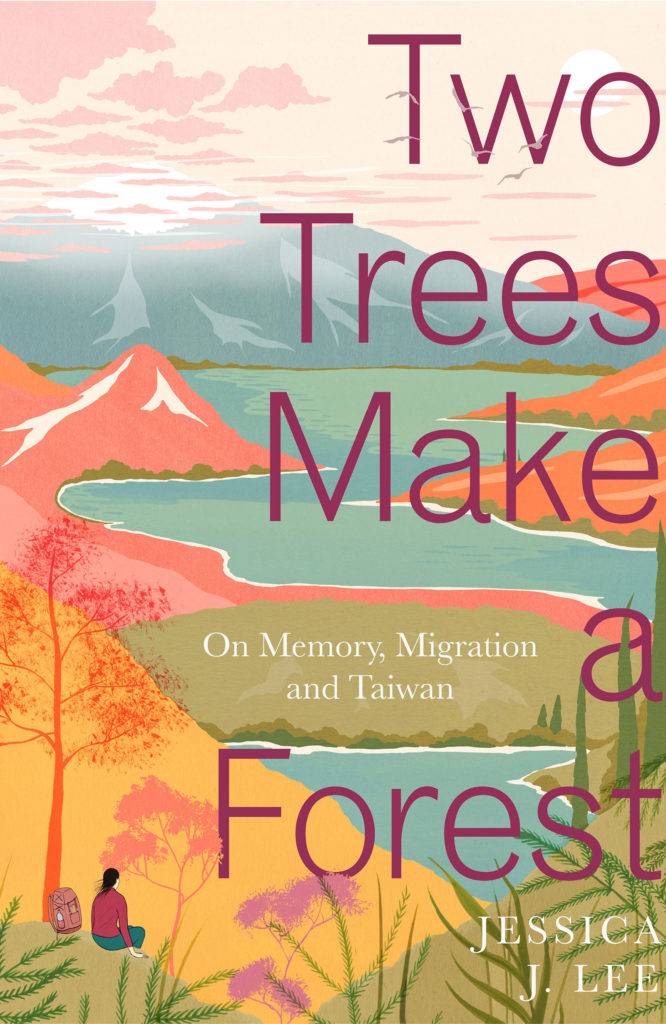

Jessica J. Lee’s second book, Two Trees Make a Forest: On Memory, Migration and Taiwan – part-nature writing and part-biography – is published by Virago, and is our Book of the Month for November. Jenny Landreth reviews.

Sometimes you can read two very different books one after the other and make unexpected connections between them. I read Ann Patchett’s The Dutch House before Jessica J. Lee’s Two Trees, and at first they make an odd pairing – but. There’s a current writing fashion where books constantly switch narrators and time, to give an illusion of pace. I find it annoying – it’s not that I need everything linear, I just like a narrative arc, not narrative Lego. Neither The Dutch House or Two Trees are fully linear, they hop about between different bits of the past and present. But they do it through skillfull weaving, instead of chunking it out in blocks. It requires that you trust the writer. The results are more absorbing, better reflecting, perhaps, the way we store and replay our own stories or memories. Writing with a gymnastically precise control, both books are an absolute lesson in what good and careful construction does to a reader’s engagement. Mine, at least.

With The Dutch House, I felt I was leaning forward from the back seat when Maeve and her brother sat in their car smoking. I was similarly engaged, curious, and moved with Two Trees, only with real people and, surprisingly to me, with one of the main ‘characters’ of the book, Taiwan, about which I came to this knowing next to nothing.

There is little Taiwanese nature writing, Lee tells us, that has made its way into English; obviously she’s started from the other direction, and nature is just one layer. The island’s history and geography are revealed factually and experientially, through visits to the island by Lee with her mother, and then alone. The most affecting strand is that of her maternal grandparents, Gong and Po. The two trees, I assumed, of the title. When a letter is discovered written by Gong, telling disjointed parts of the story of his life in China, Taiwan and Canada, it’s a chance for Lee, and us, to know the man. It is in Gong and Po that her writing most come alive. She brings the same precise attention to them and their material, domestic world as she does to the natural one. When she writes about departures – when Po last sees her mother, or when Gong takes his final trip from Canada to Taiwan, his mind fogged with Alzheimer’s – she creates a very tangible sense of sadness.

Writer Nell Frizzell captured Lee in a tweet, calling her a ‘seriously knowledgeable damp-hiking meganerd.’ There is lots of damp hiking, and some lovely moments of underplayed and surreptitious swimming. There are also clouds, myths, hauntings and ghosts, landscape and stone, birds and plants, alongside rich and tempting descriptions of food. Through the mist, Taiwan is revealed, and in other mists, things – trees, her grandfather – disappear. She is attentive and alert to nature, thoughtful and clever in how she describes the tittering of birds, or the ‘electricity of cicadas.’ Yes, that’s exactly it. That lightness of touch is sometimes leavened with words I didn’t know. Lithic. Gneiss. Orogeny. Bryophyte. But I trusted Lee, that she chose them because they were perfectly right, not for elevation or distance. She wears her intelligence kindly, and I was alert to it everywhere. When she wrote ‘I am witnessing the sublime’ I thought, ooh, I don’t know, is that layered? But maybe not. Maybe sometimes things are just as simple as they seem.

Lee knits all her strands together and tells us that she’s doing that. ‘I stitched the stories together in my mind’. ‘Layered stones’ she says, ‘tell the story of a mountain’. Gong and Po’s bungalow at Niagara Falls is also an island; Gong was a pilot, and Lee also circles to land. So the book becomes a dense, woven fabric. Occasionally, for example when she is crossing landslides on a trek, I lost my footing slightly. I couldn’t find where or when we were, I was sliding. And then she bought me back to Po and Gong, and I was sure-footed again.

Contemporary American fiction is often my first choice, so The Dutch House was an obvious pick for me. Why resist the one in the big spotlight? But I’m glad to get the chance to shine a small light on Two Trees. It gave me more, and it will be this book that I press on people. It’s a story of age, loss, lives and achievements that mean everything and ultimately nothing. It’s about belonging, and trying to; about the specific difficulty of articulating who you are, on this particular island. Maps create story, but so does nature. ‘It is in plants’, Lee writes, ‘that Taiwan’s recent history can readily be seen’. Alongside that, a story of migration, home and memory. So much, so deftly crafted. And shot through with colour: everywhere green; the orange of Po’s dress, the yellow of hot peppers.

This is a thoughtful, intelligent book written earnestly and finely. There’s not a scrap of whimsy, it is disarming and honest. Lee finds in Taiwanese nature writing ‘rather realist worlds…subtle but matter of fact, not elegiac, though so often they deal with loss’. It seems that with Two Trees she’s found her home there. To say it would make a fantastic film is not to undermine the book. I just want more of it. I want to see Gong in his plane, Po in their Canadian bungalow, the Oldsmobile. I want to see more of Taiwan. I want this to be just the start.

*

Two Trees Make a Forest is out now and available here, priced £16.99.

Jessica J. Lee reads at our events in Todmorden and Huddersfield next week, for which there are very limited remaining tickets. More information here.