It’s time once again for the annual series of postings we like to call Shadows and Reflections, in which our contributors and friends look back on the past twelve months. From Jelle Cauwenberghs:

A year ago I thought I would leave this island. A year has passed and I am still here.

Things were broken then, but they seem irreparable and jumbled now. The shipyards are empty and the trains are late. Water on the tracks, and the docks are dry.

In her essay ‘Kinds of Water’, Anne Carson writes, ‘The mechanisms that keep us from drowning are so fragile: and why us?’

It is the day after the general election and I am wondering why I am still here. Why me? Why us? – in a country that feels like a closing door, a rusty sluice that broke because the mechanisms were fragile.

I feel unsettled and furious. Some of the reason for my staying is my irrational love for my city; but most of the reason is fear – a similar lack of rationality. A vagueness I cannot place. It goes against my will. Is fear a failure of willpower? Can water be bad?

‘Kinds of water drown us. Kinds of water do not,’ Carson writes.

I am angry. I am tired. Ripples of hope reached me, then receded. It has been a long and draining year, not just politically, but also personally. I will not go into details but let us say I am grateful for good, free health care and the support and love of my partner. This year has tested my faith in writing but more importantly it has tested my faith in humanity. True, I have come close to being the first to close the door and to draw a line because I was drowning in work and debt and worry. I have scraped against the hollowness of words. I have bought furniture to make myself happy. A dear friend faces deportation and all I can do is make him coffee and tell him it will not always be like this.

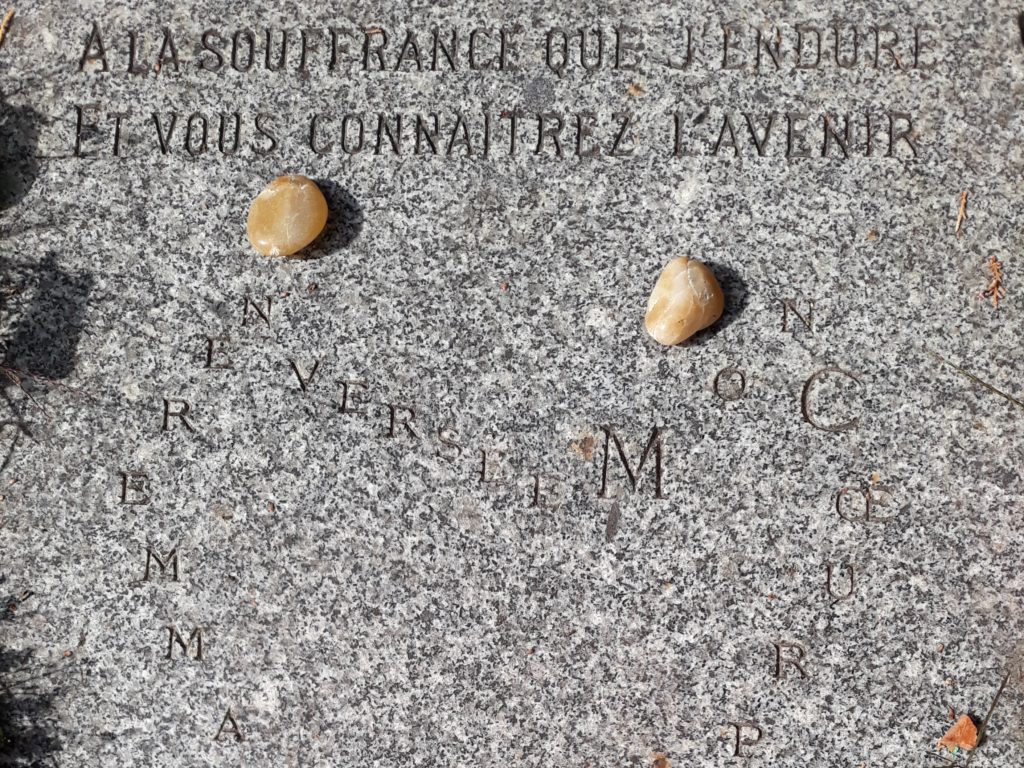

I am reading to restore my faith in language. I am studying again. Poetry, novels, essays. Reading feels like gasping for air. It also feels like piecing words together on a gravestone. Mon coeur pareil à une flamme renversée. I discovered Carolyn Forché’s anthology Against Forgetting: Twentieth Century Poetry of Witness (1993) which has seeded my life with poems that float like ash from a great, unextinguished fire. The world has never stopped burning.

What does it mean, to bear witness? Once or twice I went away to write in a small house in a field. I needed to hear the water under the house.

I have this notion that words are living matter, not dry wood we pile up in a barricade, though of course deadwood is home to living things that deserve to be named, like longhorn beetles and wood lice and oak splendour beetles. And perhaps they are the true nature of language; those invertebrates that find their future in decay.

But so does water.

One of the things I love most about poetry, and my practice of poetry, is the daily reminder that the ordinary is fluid and porous and impatient. Language is perhaps the best illustration of that state of unrest and our surrender to near-drowning.

Language is strange. The human mind is not inert and docile. It turns old men into foals and washing lines. It looks at crocodiles and talks about melons. The idea of order is disorder, the starched apron of the page covered in telltale stains. Through my days of low-paid labour I feel the movement of that bright current of poetry in my brain and I know I can keep that door open for the unexpected and I can survive this slow evisceration of my joy.

What else can I do? There are many of us who go back to poetry to find what it is we need to carry us through the days, to voice our grievances, and to take the power back; one ripcord syllable at a time, like Emily Dickinson – who believed so wholeheartedly in cordiality and correspondence with all living things.

I went to see the Sally Mann retrospective ‘A Thousand Crossings’ at Jeu de Paume in Paris, after I went to see the exhibtion ‘Préhistoire’ at Pompidou which paired modern art with images and objects which preceded them by tens of thousands of years – a short geological leap and clearly, the thesis of the exhibition was the insignificance of that leap when it comes to the questions that bind us and divide us and lead to so much wonder and destruction. The juxtaposition of prehistoric art and questions of damage and repair in historical landscapes was powerful and disturbing and uneasy.

I left the city feeling at once far from nature and incredibly close to its spectral, erotic qualities. Sally Mann had captured the starlight and the darkness of fields in which photography first documented the casualties of war and the rivers in which bodies were drowned – nature as indifference, as silent witness, as healer – perhaps, unanswerable, blindly oracular. The blue pigmentation of Yves Klein’s Anthropométrie ANT84 (1960) gave me a shock of recognition and oversaturation, but what I recognized and was struck by was simply the vitality of a body escaping my reading of it: the nautical body of a woman that seemed to return the gaze of a drowning person in a white abyss, the way the scarred tree in Sally Mann’s photo Deep South, Untitled (Scarred Tree) (1998) can be said to tell us everything and nothing about the hurt we have caused, to each other, to nature.

I read somewhere that we should not let politics stop us from seeing the fabric of life. That is true. But neither should we assume that bad politics do not impact the fabric of life. Some of us voted in favour of annihilation and misery. This is a time of decline and erosion. We are not sheltered in a great wood or a homestead in Amherst that can withstand this pressure from a distance. We stand on the slippery bank of a floodplain and the light is sharp and immediate.

Seeing is the beginning of action and pain, yes – acute pain. The personal is political. We are all witnesses. If we shrink away and stay silent, we diminish our circle of action. Poetry is all about the construction of that circle, a buoyant bower of branches – it is made of words, it is made of people and animals and minerals, it is made of living things that grow and feed beneath the surface, no matter how dead and hopeless that surface may seem; because sometimes the bower is buried like a small goddess and we wait for the rain to lead us back to the river.

Poetry is not about being seen or validated in your silence. It is born in introspection and linguistic speculation, but it can also die there like bone worked to dust. I am aware of the work silence can do. Silence can be a safe space in which there is time to think and time to slip away. Silence can be a cave. But silence must eventually lead us into the street; regardless of whether that street is a street of stone or a street of tall, wavy grass, a prairie with one bee, a wine-dark sea, or a street of broken glass and icy puddles in which trains disappear. It is always a street of shadows and reflections in which choices must be made as to the direction of the gaze, the company we keep, and the movement we produce – the decision to float, or to sink like a stone. The Belfast poet Ciaran Carson puts it beautifully in his poem ‘Let us Go Then’ from his collection On the Night Watch (2010),

Through the trip

wired minefield

hand in hand

eyes for nothing

but ourselves

alone

undaunted by

the trips & pits

of wasted land

until

you stoop

& pluck

a stem

of eyebright.

Transform the most deplorable reality with art. That is really all that we can do when we make art. Point out what is wrong and damaged – sure, but celebrate also what is good, and small, and bright – and expand it, make that your final destination. As Dorothy Molloy writes at the end of her poem ‘I wake up in quicksand’ in her collection Long-Distance Swimmer (2009) published posthumously,

Suddenly there is light and

oxygen, and the heart picks up its

heavy load and

walks.

We are the fragile mechanisms. We must keep walking, until we can go no further.

I will write until I can no longer see and say what I see – and there is so much to see and say.