It’s time once again for the annual series of postings we like to call Shadows and Reflections, in which our contributors and friends look back on the past twelve months. From Paul Scraton:

What does it mean to become a new citizen of a country, different to the one where you were born and grew up? What does it mean to call two places ‘home’? And what does it mean when a friendly woman from the citizenship office hands you the piece of paper that confirms your split identity and welcomes you as a German with all the rights and responsibilities that it entails?

On a sunny autumn day I stood on Mathilde-Jacob-Platz in the Moabit district of Berlin, holding that piece of paper and with the friendly woman’s words echoing in my head. After eighteen years of living in Germany I hadn’t imagined that the process of applying for citizenship would change much. I didn’t think it would change how I thought and felt about this place where I spent most of my adult life. But as I walked home through those very familiar streets, I realised that it had.

About an hour before, early for my appointment, I looked up the name Mathilde Jacob on my phone, wanting to find out more about the person for whom the square was named. A small plaque on the wall of the council buildings outlined a brief biography, and the internet supplied the rest. Born in 1873, Mathilde Jacob was the daughter of a Jewish butcher and grew up in Moabit. In adulthood she became a stenographer and typist, founding her own small agency, and it was in this role she became a friend of Rosa Luxemburg, typing up many of her speeches and articles.

When Luxemburg was imprisoned during World War I, it was Jacob who visited her, navigating the bureaucratic requirements to bring small gifts to her friend while returning through the prison gates with smuggled writings ready to be typed up. She was at her side at the founding of the German Communist Party, and in 1919 it was Jacob who travelled out from the city to a military base to identify Luxemburg’s body, months after she had been brutally murdered and dumped in a Berlin canal.

After Luxemburg’s death, Jacob continued to type, write and fight for a socialist future in Germany and beyond, and was also tasked with managing Rosa Luxemburg’s literary afterlife, including smuggling letters and other writings to the United States after the Nazis came to power in 1933. Not much is known about Mathilde Jacob’s life under National Socialism, living off a small pension and forced, like all the Jews in the city, to wear the yellow star stitched into her clothing.

In June 1942 Mathilde Jacob received a letter. She was to be deported from the city, but before that happened she was required to fill out a declaration of all her assets. The eighteen pages of the document included furniture, clothes, cutlery – everything, indeed, that she owned – and with her signature at the bottom it was now the property of the German Reich. Later, after Mathilde Jacob had been taken from the city, her landlord would be able to access some of the proceeds from the sale of her former belongings to pay rent and repair costs due on the apartment.

She was taken first from her apartment on Altonaer Straße in Moabit to a Jewish old people’s home on Große Hamburger Straße in Mitte, now being used as a collection point and internment centre for Jews from across the city. On the 27 July 1942, at around two in the morning, Mathilde Jacob climbed into the back of a truck that took her through the nighttime streets to Anhalter Bahnhof. There, along with 99 others, she was taken from the city in special carriages coupled to the regular 6.04 train to Dresden. Her final destination was Theresienstadt, a fortress city turned into a concentration camp, where she died less than a year later in April 1943.

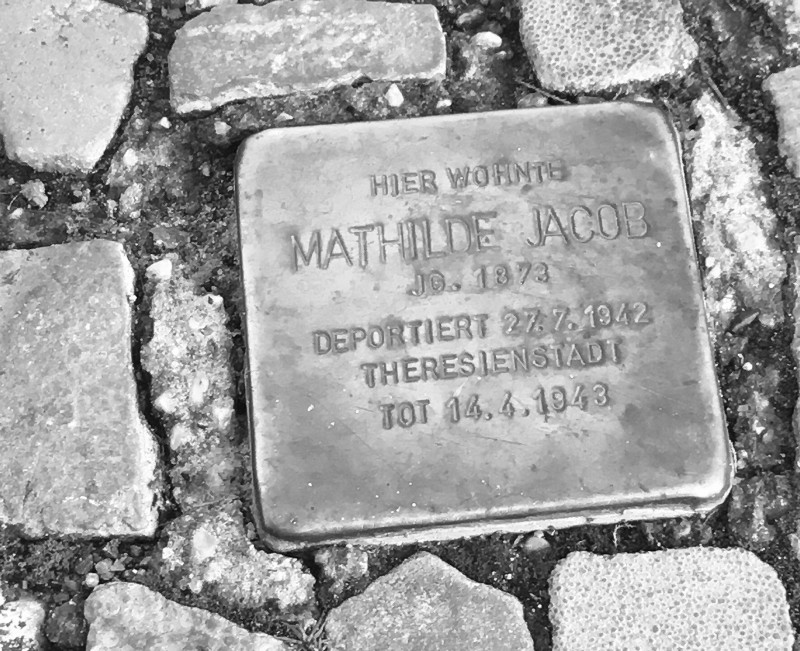

A few weeks after I received my citizenship on Mathilde-Jacob-Platz, I found the small brass cobblestone laid into the pavement where her apartment building once stood.

HERE LIVED

MATHILDE JACOB

BORN 1873

DEPORTED 27.7.1942

THERESIENSTADT

DIED 14.4.1943

I had decided to follow her final journey through Berlin, walking from Moabit to Große Hamburger Straße and on to Anhalter Bahnhof. I wanted to do it as a way of recognising her story and a way into telling it, of sharing the life of Mathilde Jacob in my own version of that little brass cobblestone in the pavement. And I wanted to do it because of the words of that friendly woman as she confirmed my new status, as I couldn’t help but feel that taking ownership of this history was part of the responsibility she was talking about.

Even as I stood there in the early morning sunshine, I asked myself the question: Could that be right? Do we have responsibility for the crimes of the past? For events that happened long before we were born? As I walked from Altonaer Straße, following the S-Bahn tracks and surrounded by a whole city neighbourhood that had emerged from the rubble of the war, I tried to imagine what Mathilde Jacob saw from the back of the truck in the middle of the night. Did she see the ruined outline of the Reichstag? The facade of the Deutsches Theater? The golden domes of the New Synagogue? It was impossible to know. Of course it was; imagination failing right at the moment when I needed it the most.

Still, we remember those things we were not around to experience. On Große Hamburger Straße, the old people’s home where Mathilde Jacob was interned would later be damaged by bombing raids and eventually cleared, to leave behind an empty space in front of Berlin’s oldest Jewish cemetery. Today there is a memorial there, a collection of figures who represent the 55,000 Jews from the city who perished in the Holocaust. I have passed the memorial many times. I have taken school and university groups there, as well as friends visiting the city. But Berlin is not a museum, and the streets around the memorial hold many personal memories too. The stories of Berlin and German history mingling with those of my own time in the city and those of my friends and my family. Nights in restaurants and bars. The hospital where my wife was born. Places of work and apartments of friends. Layers built upon layers.

The main overground part of the station no longer exists, and the Anhalter Bahnhof that is in operation today is an underground station, part of the S-Bahn suburban rail network. Heavily damaged during the war, the front facade stands as the only reminder of the place Mathilde Jacob would have entered on that July morning. I walked across the street and up the steps, passing through the main entrance to face not the tracks and platforms laid out beneath a vaulting roof but a football pitch and concert venue, occupying the space where the station once stood.

A small sign next to a patch of open land behind the station facade details some of the story. Altogether, 9,600 Jews were taken to Theresienstadt from Anhalter Bahnhof on a total of 116 “old people’s transports”. These convoys were made up of third-class carriages attached to the back of regular Prague and Dresden trains. They would have approached the platform like any other passenger, except for the guards and the yellow stars on their clothing. So not like any other passenger at all…

Beneath the old station building, on a subterranean concourse leading to the S-Bahn platforms, a series of photographs shows how the station would have looked when it was the last place in Berlin Mathilde Jacob would see. I thought again about the history of the city I have lived in for so long, and the idea of our responsibility to the stories of the past. The writer WG Sebald certainly did not believe in the idea of inherited guilt, but also said these words which continue to resonate long after he himself has gone: “I’ve always felt I had to know what happened in detail, and try to understand why it should have been so.”

A hundred years ago, Mathilde Jacob travelled out from Berlin to identify the body of her friend. Nearly eighty years ago, she was taken from her home city for good. To know what happened and why remains as important as it ever did.

*

Paul Scraton’s Berlin novel Built on Sand was published earlier this year by Influx Press.