An extract from Tom Bolton’s London’s Lost Rivers: A Walker’s Guide, Volume Two – our Book of the Month for January.

Chapter 3: Cock and Pye Ditch

Practicalities

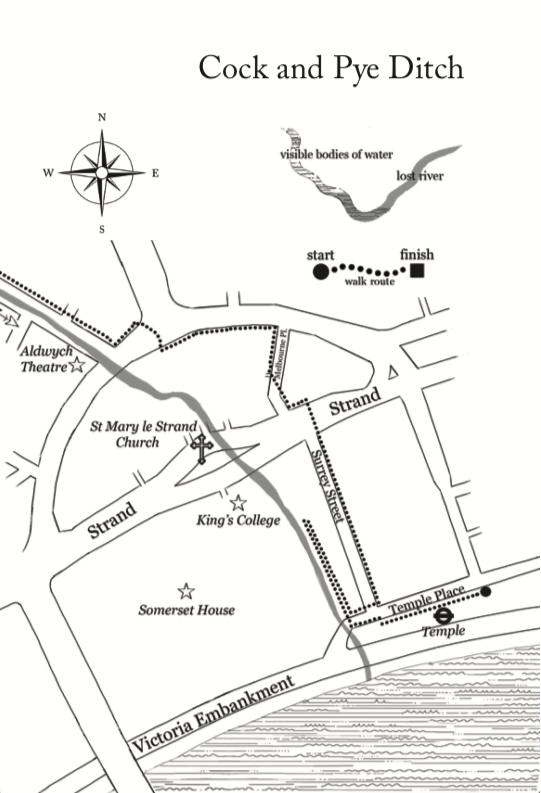

Distance – 1¾ miles

Start – Victoria Embankment Gardens, Temple Place

Getting there – Temple Station.

End – Cleopatra’s Needle, Victoria Embankment

Getting back – Embankment Station

Note – this walk should be completed between 7.30am and dusk (or 9pm, whichever is earlier) to allow access to Embankment Gardens, open between these hours every day of the year.

Introduction

The Cock and Pye Ditch, the Bloomsbury Ditch and their associated channels may or may not have, at one time, been rivers, but certainly carried water. They drained land that is now Covent Garden, carrying water to the Thames at Embankment and Temple. The ditches were the most prominent part of a system that kept roads relatively passable and drained the marshy land around the village of St. Giles, surrounded by fields on the road to Oxford, outside the City of London. With no known natural watercourses between the Fleet, to the east, and the Tyburn, to the west, Covent Garden and Soho are gaps in the London river map. It is, however, quite possible that the ditches rechannelled small streams that existed before the earliest maps. Today, the sewer system still sends water along the routes of the two ditches. This walking route follows the two linked ditches, tracking them from outfall to outfall and, unusually for a lost river walk, both starting and ending at the River Thames.

Until the 17th century, when it became absorbed into London and rapidly transmuted into a notorious slum, St. Giles-in-the-Fields was a small collection of houses in the grounds of a leper hospital, which had been founded in 1101 by Matilda, Henry I’s queen. The Cock and Pye Ditch encircled a marshy field called, appropriately, Marshland. Until its name changed to reflect the nearby pub, it was called the Marshland Ditch. The last open area to be developed in Covent Garden, Marshland was covered by Seven Dials and its radiating streets in the 1690s. The ditch made a full circuit around the entire field – a rectangular watercourse. The Pituance Croft Ditch, which drained a field outside the hospital gates, seems to have been next to the Marshland and may have been connected to the Cock and Pye Ditch. Several ponds are also said to have been scattered across St. Giles, and another field in the hospital grounds, Pool Close, sounds very much as though it contained one, and possibly contained the source of some of the water that fed the ditches.

Connections from the Cock and Pye Ditch to the Thames are harder to track. We know that the ditch connected into a channel that ran along St. Martin’s Lane in the direction of Whitehall. In the 1670s it was arched over to make St. Martin’s Lane more passable, and its water diverted east into the Bloomsbury Ditch. The Bloomsbury Ditch, also known as Bloomsbury Great Ditch or the Southampton Sewer, is part of a system of connected drains that separated the parishes of St. Giles and Bloomsbury, and continued to act as a boundary as the city developed. In the 19th century the entire route could still be traced as a parish boundary, from the Cock and Pye Ditch at Seven Dials to the Thames at Surrey Lane. Its name was originally, according to 19th century historian John Parton, Blemund’s Dyche after William Blemund, medieval owner of a large house in St. Giles. While these were the two main ditches that drained St Giles, the local network also included Spencer’s Ditch, which ran along the south side of Holborn, and another unnamed ditch that surrounded Lincoln’s Inn Fields.

Any walk along lost rivers in this part of town is also haunted by the mythical or semi-mythical watercourses of Soho. The two key players in these stories are the Cranbourn and the Dean, two rivers which may be explained by the Cock and Pye Ditch. The Cranbourn is said to flow under the London Hippodrome, on the corner of Charing Cross Road and Cranbourn Street. The latter, however, is named a title belonging to the local landowners, the Earls of Salisbury, not a river. Further north into Soho, authors Nicholas Barton and Stephen Myers report a watercourse that was visible through a grating in the basement of No.4 Meard Street when it was the Mandrake Club, a bohemian post-War Soho venue.

These supposed rivers are debated in the surprising context of a Lord Peter Wimsey mystery Thrones, Dominations, in which a taxi driver tells the detective “I don’t know as how the marsh under Seven Dials ever did drain into the Fleet“. Wimsey suggests the Cranbourne may have connected the two, but the sewerman doubts the existence of the Cranbourne and suggests that if the marsh drains into the Fleet it does so “down lots of little courses that have lost their names long ago along with their daylight.”[1] Illegal sewer diversions in the 17th century may have been responsible for redirecting water from St Giles into Soho. The Westminster Commissioners for Sewers concluded that Richard Frith – who built houses on Soho Fields in the 1670s and has left his name at Frith Street – had connected a sewer in Soho to the St. Giles and St. Martin’s parish sewer without permission. The latter was the Cock and Pye Ditch, and its flow may have been diverted under Soho, generating the illusion of a river to occasionally be glimpsed under its theatres and clubs.

This walk traces the probable course of the St. Martin’s parish sewer from the Thames as Embankment to the Cock and Pye Ditch, and then follows the latter into the Bloomsbury Ditch and back to the Thames, to reveal something of the deeply obscure watercourses of WC2.

[1] Sayers, Dorothy & Paton Walsh, Jill (1998) p.311

*

London’s Lost Rivers Vol. 2 is published by Strange Attractor Press, and is available here, priced £11.99.