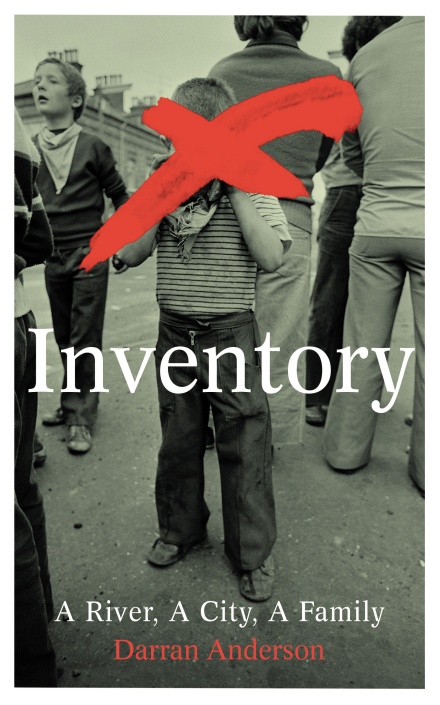

Kerri ní Dochartaigh reviews Darran Anderson’s astounding memoir Inventory – a tale of Derry, the Troubles, loss, grief and survival.

‘Memories of the outside world will never have the same tonality as those of home and, by recalling those memories… we are never… historians, but always near poets…an expression of a poetry that was lost.’ — Gaston Bachelard

*****

‘How might it be possible to reconstruct a lost person? To thread bone onto soul…a presence in the shape of an absence.’

I first came to him last June, on a lighthouse-bright, crow-craeeekkked St John’s Eve; ‘Bone night’.

I first came to him across the border, having followed the gently carved meanderings of the River Foyle, from my hometown, and his – past Culmore Point, then Quigley’s Point – to the body of water’s western banks at Moville; where the River Bredagh flows into the sea. ‘The most silent, innocuous stretches of land contain memories of what once happened there, and we are only sheltered from tragedy and brutality by the thin ice that we call time.’

I first came to Darran Anderson in the second ‘Winter Papers’ journal – the only reading material on my person for that solo trip – I was there to write. I opened the journal at a random page, as always, and I found him there. The first line I came to shocked me to my core, as I had the exact same line open on a word document of my own in front of me: ‘I grew up in a terraced house in Derry.’ When I first came to Darren Anderson it felt like meeting a reflection in a river.

The book that grew out of that exquisite, unsettling piece begins in the place where I was born (Derry), in 1983 (the year that I was born). Its author had been carried home by his teenage ma, from the same hospital, three years before; to the opposite side of that hungry, fated black river from the one my teenage ma carried me. Inventory maps the everyday – the events of lives lived on the edges – of place, society, family and self. It does not stick to a simple format or linear chronology; life does not work that way – that much we all know to be true, no matter where we were born, or into what tumultuous state.

‘The strange thing was that none of it seemed strange.’ Inventory explores Derry, the Troubles, loss, grief and survival through a collection of objects. It is a book about family, history, illness, death, life and all that is found in the cracks in-between. It is divided into parts, each as disturbing as the other; as full of truths that we all need to know. Content wise – we have trauma, loss and suffering. In other words, we have the telling of lives lived during the Troubles – in their run-up too, and now; in the aftermath. Bombs, terrorists, bloodshed, fear, the army, war, poverty, darkness, the RUC, drowning, suicide – alongside music, drugs, birds, the seasons, trees, the gorgeous sky; we are given truth – free from filter, shone under the light of the author’s own constant honesty. Anderson wears his darkness well – that shroud those of us who grew up at that hallowed, hollow hinterland may never quite shrug off.

Some parts were harder for me to read than others – his father’s pigeons, his mother’s childhood – the loss that seeped into all of their lives over and over; I wanted it all to stop for them, I wanted to give them peace. Anderson was born at a cusp moment, an almost stopping place during the violence our city was battered by, and the difficulty those of us born half way though the Troubles experience is portrayed with such skill. The idea of his hometown as a place still capable of change is one of the best lines of examination Inventory follows: ‘We lived merely in the most current incarnation of Derry. Who knows what versions are to follow?’

The poorer parts of the city did not see much ease at all when we were growing up. The weans we beat about with from other parts of town would have no idea of the bedlam that still ensued on our housing estates – the ones where the electricity meters rang in time with sirens; poverty bells. Trying to cope with feeling like an outsider – worse still, a liar even – is a thing hard to put into words but Anderson does, talking of yet another battering he got that he simply didn’t deserve: ‘They didn’t believe me. These things didn’t happen anymore.’

There is shame in this book, self hatred, worry and more. It shows men and women, old and young, here and gone: suffering, mostly in silence. It is so, so hard to read – not because it isn’t well written – quite the opposite, in fact. It is so well written it hurts to read this book. Its author is part of a generation that is almost undefinable, especially to ourselves: ‘I struggled with seeing myself, even in mirrors.’ There is an element to Inventory that is about learning to see oneself, to look, to accept; at long last.

The chapter ‘Belt’ made we weep so badly I struggled to breathe. I cried at much of this book, and laughed my belly sore at much of it too. The writing is intoxicating. The sheer fucking poetry of it all, the splendour and the decay, the beauty and the horror; the unearthly, moon-lit sorrow.

It is chilling to read such excellent writing about places, people and things you too know so intimately, and there are so many crossovers in our experiences that it leaves me shaken. I imagine the times and places where we may have encountered one another across the years; their span like that vast, concrete brutalist bridge we are both somewhat acquainted with. I see the traces of those points where we could have met. In the queue for black taxis after nights upstairs in the Gweedore pub with friends that were off their faces, and fuck all money in our back pockets, as the snow swirled around on the drunks we couldn’t get out of our minds – asleep outside – and then sometimes not asleep: sometimes gone, and never coming back. (The episode with Anderson’s alcoholic family member broke me into wee pieces.)

I watch us at the top hut at Fort Dunree – finding bones of lost things, watching lights that flickered and flared; remembering other lights, other fires, other signals that spoke – not of safety, but of its opposite. I watch us in the back laneway of various impoverished council estates – glass and bullets, warnings and boarded up houses –no safe place to be hollowed out anywhere at all, but when I see us: we have found the nooks. I see us, as years bleed into the dark hole of time – still there, in that oak-fringed city, with its bombs and soldiers, its walls and drinking, its class sense of humour/ dress sense/ taste in music/ etc – but there are ghosts (why so many fucking ghosts?) – clawing up from the insides of our guts. ‘If ghosts did exist they’d be everywhere.’

In the last image, we are gone – he just before me, me quick at his heels – down, down, down – up and over, away: gone. Away from Derry; away from its river. I watch us swallowed, I watch us sink, I watch the potential for drowning seep into the picture like a mauve-grey veil above the stone circle we used to know, once. The snow falls. The lilac becomes grey. There is silence, and the unearthly light – of places not quite real.

‘We took up residence as birds do in eaves or rats do in sewers.’ Talking of places, Anderson is off the scale good in how he paints them for us. The places we grew up in are, on one hand, abandoned and dirty – liminal and terrifying. On the other hand those places are almost too beautiful to find words for – bathed in colours that don’t exist in other places. We hold the rain and the winds back from ye who dwell to the right of us but there are other things we in this wee rock hold back too. Anderson paints these other things like a master.

‘Staring out at a city that lay like a sea of slate beneath a moon that knew all secrets…something changed then. I wasn’t quite sure what. Perhaps there was simply something miraculously precious about this miserable, beautiful life.’

In a piece this week in the TLS Anderson summarises: ‘Those who are confined dream themselves to the world outside through their writing. It is unlikely that the world dreams of them nearly enough.’ It is fiercely important for me to let Inventory’s author know the impact of his words on the world, speaking from my wee part of it; that same dark, cold corner he was born into too. This book is brave. This book is brilliant. This book will help so many to break silences they should never have been forced to keep, about things they should never have had to live through. At the penultimate chapter of this book, I lifted my phone and whatsapped the following set of messages:

ME – ‘Bluetits love the sunflower seeds. Was it IRA in your van daddy? Was it scary? Xxx’

DAD – ‘no loyalists paramilitaries.x’

ME – ‘Daddy I really wish you hadn’t had to go through that. Did they drive you through checkpoints? How long for? So horrific. I dream about it you know. X’

DAD – ‘yes. 30 mins. I have 2 SF feeders in the park. Chaffinches, blue/great tits &goldfinches love them. Love you.’

*****

‘This is how quickly the abnormal becomes normal’.

I have tried to ask these questions for decades, since the night my da’s video-van was high-jacked by armed terrorists, while he was out trying to bring in enough money to feed us; the day the whole world as I knew it changed. It always felt like too long had passed, like the ice that covered that time period was too thick, like it was his suffering, his ghosts, and that I had no right to unearth it all. But, as on both sides of Anderson’s family – trauma ricochets. We are passed it down through the bloodline – like the clothes of our cousins, the shape of a nose, the taste for a drink – or for the river: ‘These are the weights that children bear that are not theirs to carry.’

The events of the past mutate, they ripple – all the more grotesque for our inability to look – to really look, and to listen. These simple messages between my father and I, like this brutally raw memoir – speak of something that is so much thicker than blood. They speak of history, they speak of honesty, they speak of the North of Ireland; they speak of letting go. Good writing does that; it makes us braver than the sum of our parts. The view of the Troubles offered to us by Darran Anderson is such that we want to look things in the eye, as close as we can; we want to see the truth so we can learn, we can understand, we can heal.

This book has entered my dreams, my conversations, my Whatsapp folder, my lines of questioning, my bloodstream – and fuck am I grateful it was written. We need this book, and by ‘we’ I mean every single bleeding one of us.

‘In truth there are many ways to drown.’ …But in even more shocking truth there are many ways not to drown, despite the encroaching darkness all around; the fear that silvers our skin like sheening mackerel guts. Inside this harrowing, haunting book, Darran Anderson has hidden maps; concealed diagrams to guide us through, like the faded etchings in stone – on those ravaged, historical Derry Walls. In alongside the real geographies – so exquisitely rendered – there are sketches of other worlds, other places, other futures; a ghost-palimpsest. In between these printed lines you will find other objects – shadow-traces, to be held up to your own choice of light-source. I used a mirror and a crescent moon, and found image after image of invisible islands; measureless safe nooks. Hidden beneath this story’s surface, eel-like and luminous – I found boundless light-soaked coves. Places where the meandering flow of existence eases for a wee bit, where it shape-shifts – where it is no longer full of blood and hunger – where hope glistens out from a silted, sated, singing river.

*

Inventory is published by Chatto & Windus, and is available here in our shop, priced £16.99.