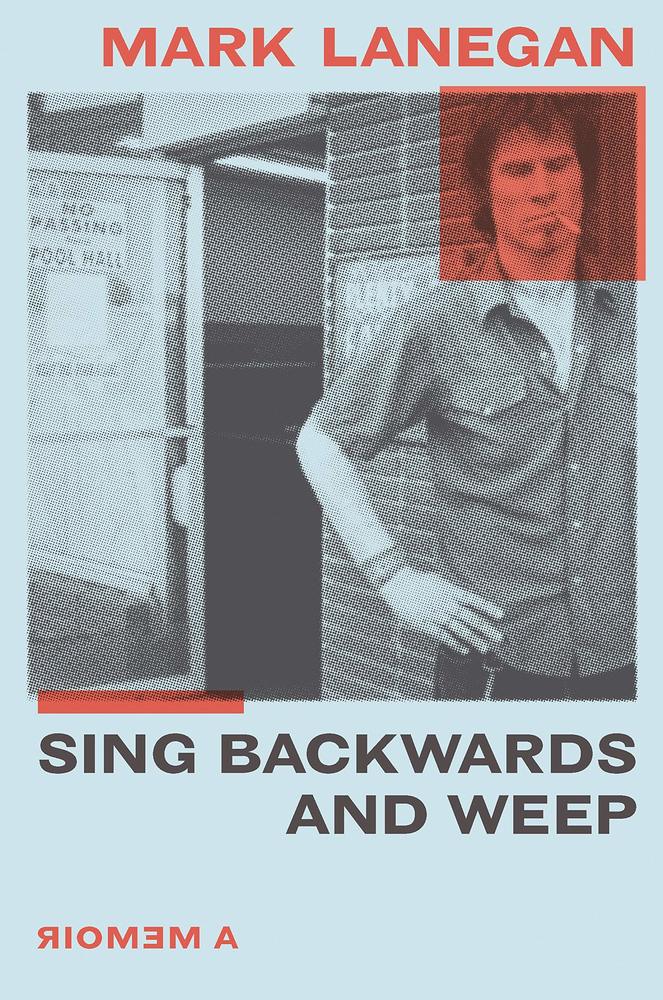

Will Burns reviews the visceral memoir of revered musician and songwriter Mark Lanegan, published today by White Rabbit Books.

In Civilization and its Discontents, Freud wrote ‘as long as things go well with a man, his conscience is lenient and lets the ego do all sorts of things; but when misfortune befalls him, he searches his soul, acknowledges his sinfulness, heightens the demands of his conscience, imposes abstinences on himself and punishes himself with penances.’ Freud is addressing something called ‘moral luck’, a phrase, indeed an idea, which might well have been coined with Mark Lanegan’s life in mind. The impact of (Freud again) ‘ill-luck – that is, external frustration’, and the extent to which luck is qualified by agency and its subsequent ethical dimension play out in a multitude of almost classically tragic ways in Lanegan’s relentless, astonishing memoir.

The book’s form is a kind of truncated ‘life’, beginning with an emotionally abusive, thoroughly unwholesome childhood that develops, through sporting and academic frustrations, into an adolescence and early-manhood so doused in alcohol that by the time Lanegan and his band Screaming Trees are beginning to tour and record, he has an almost complete drinking career behind him—addiction, rock-bottom, sobriety. His early years read like a kind of rock’n’roll John Fante novel, with Lanegan as a post-punk, North-western Bandini—cursed with bad luck, an uncanny ability to make more of his own, a debilitating lack of self-worth, and from the reader’s point of view, the same clear-eyed, almost manic straight-talking sensibility, allowing us insights as original as they are honest. Scenes such as Lanegan being disturbed masturbating in the bushes outside his recent ex-girlfriend’s place while watching her and her new partner having sex create a picture of debasement and damnation utterly removed from the usual rock-God glamour and bravado.

In some ways, the book is a kind of rock bio in reverse, or perhaps an anti-rock bio. The gaze is punk. Burn it all—no posture, no pomp. A rags-to-rags tale where instead of a troubled kid discovering art and with it, access to status, sex, money and fame in an inevitable upward trajectory, here Lanegan has some access to these things in a kind of low-key hey-day, but the trajectory is still always downward, Lanegan himself indeed intent on singing his story backwards, self-sabotaging even his moments of triumph. As the book progresses, and the various pressures of his workable yet artistically frustrating gig with Screaming Trees, his artistically fulfilling, yet apparently maddening solo career, and an ever-increasing drug dependency take their toll, Lanegan’s character evolves from the Bandini of youth into a kind of Chinaski-on-steroids. The rage intensifies, and grudges from the various strands of his life—by the middle of the book Lanegan is as much a local drug dealer as he is a rock singer—extract a painful debt, with the embers of his youthful humour, playfulness and hope slowly going out. It’s testament to Lanegan’s skill as an author that this never feels like a forced move, the process feeling as inevitable as it does dispiriting, and the honesty with which the fall is recalled generating a genuine emotional toll of its own. Here, early on, is Lanegan forging his friendships with Kurt Cobain, Dylan Carlson and Layne Staley, and articulating those friendships in unsentimental, moving prose. He is in awe of the talents of others (this remains a constant throughout), in thrall to those few friends close enough to understand him and who remain impartial to his many misdemeanours. But slowly, through the dark heart of the book, we are given the Lanegan who, in no small part due to the weight of heartbreak and pain endured from a lifetime of parental abuse, disaffection, and as an adult the death of friends and lovers, becomes a slave to his anger, his misanthropy, as well as his dependency.

The misanthropy is almost always shot-through with the realisation that Lanegan’s true enemy is himself, even as he rails against those around him, to a greater or lesser extent deserving—for every Liam Gallagher, here exposed as a loudmouth bully who bottles a showdown of his own making with Lanegan, there are the likes of an unfortunate merch man who fall foul of the inconsistencies of someone approaching their very lowest ebb. Like Bukowski’s excavations of the low life, or the unremitting violence in Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, Lanegan’s insistence on squaring up to his impulsiveness, his erratic decisions, his compulsions, the true nature of his desires and motivations and the pain they cause, with no regard for the false comfort of reputation or status, is visceral as well as profound. This is as hard-won a story as any and Lanegan’s genuinely literary construction is of a human exposed for all his weakness and his strength, which is, of course, something like living itself, as well as something like the genius of his remarkable lyrical work.

No matter how well achieved, the memoir form inevitably re-lights the genius of Lanegan’s songs and singing. Reading the book, and re-visiting his catalogue, you are struck by the complexity and depth of humanity the songs are able to communicate, in a way that, perhaps inevitably, his prose is unable to. Stripped of the adornment of music, and of the impact of Lanegan’s singing, his words have a more direct, brutal quality. Lanegan’s best work truly matches the achievements of the artists he reveres throughout the book. His obvious depth of feeling towards the music of Jeffrey Lee Pierce, John Cale, Ian Curtis, Van Morrison, Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings (these two are mentioned in touching anecdotes that deftly articulate Lanegan’s humility and respect even in his private darkest hour) are constant touchstones, and Lanegan’s great records (his is an astonishingly consistent catalogue and he continues to make records of high quality, but Whiskey for the Holy Ghost, Field Songs and Blues Funeral are, to use Lanegan’s own phrase, genuinely ‘timeless’ records of the very highest genius of American song) bear up to anything any of his influences made. Lanegan’s musical ambition has expanded over time and left a wholly original body of work—a touch of a heavy, even darker Fred Neil, through to the ‘Dark Disco Jag’ of his more electronic music. It is that singular singing voice which carries over the depth, the heaviness, of what it is to be alive and the mess that brings, before accounting for the lyrical quality of his songs—which, through accumulation over a series of records and years, communicates that mess with a richness and a beauty that is all Lanegan’s own.

He has said himself that ‘the true gift of this book’ has been another batch of songs and a new record that he is as proud of as any, and that, perhaps, is the point of a book like this; to add some new shadow to that voice, to further humanise those monumental lyrics. Nobody who has listened attentively to Lanegan’s music could ever doubt that his blues were for real, but reading this book provides any confirmation necessary, and puts those strange and beautiful songs, that immense singing (Johnny Cash—“I’m sorry I don’t remember your name, son, but I remember your singing. You almost put me to shame at those shows!”) back in the middle of your mind. And after reading what he has been through and what he has put himself through, others through, all that music represents a truly human triumph.

*

Sing Backwards and Weep is out now, and signed copies are available here in our shop, priced £20.00.

Alongside artists including Bobby Gillespie, Duff McKagen, Alison Mosshart, Liela Moss, Dylan Carlson and Peter Hook, Will has assembled a playlist of his favourite Mark Lanegan songs for The Vault – a platform celebrating Lanegan’s extensive catalogue. You can listen to his selections here.

Will’s first full-length collection, Country Music, is newly published by Offord Road Books, and is our current Book of the Month. Read Declan Ryan’s review here.