Following on from yesterday’s introduction and Melissa Harrison’s poems, today comes a prose piece by Alexandra Harris, inspired by items from the archives of Museum of English Rural Life, and written for their ‘Museum of the Intangible’ project.

From 1529 until 1782, the law in England and Wales required that an inventory be made of a deceased person’s estate before probate could be passed. This means that the storerooms of local record offices across the country and of the National Archives in London contain thousands and thousands of lists. Item four pigs, item fourteen quarters of barley, item one dozen of napkins, item goods in the milkhouse: outside and inside, room by room, the items of lives are spelled out. In a great many cases this is the fullest account to survive of an individual’s existence. An account, literally: added up at the end. What will survive of us? What has survived of generations of men and women are lists of furnishings and utensils. It seems, simultaneously, so much and so little: to know the number of a person’s pillowcases is to be on intimate terms, and yet, knowing only their linens, what can one say of the mind that lay down to sleep?

Occasionally, in rare and wonderful collections like that at the Museum of English Rural Life, the goods and chattels themselves survive. Invited to explore the archives, I unfolded linens and felt the pattern of lathe-turned chairs; I grasped thatching hooks and compared the weave of baskets. Objects listed in the inventories were here in my hands, as well as the small things usually lumped together as a single item called ‘hastlements’, or ‘etc’, or ‘other trash’, things such as wooden scoops and cheap rushlight holders made by the local blacksmith. I took them in my hands and to do so seemed, again, so much and so little. Perhaps it was only because I was holding a butter mould, but I began to think of the way that physical objects bear our imprints, or take the mould of us, and the way we shape ourselves, habitually, to the things we use.

I worked the little lever of a rushlight holder and saw how it would grip the rush. Then I wanted to know things that could not be learned from objects alone, like when to harvest rushes, how to dip them in fat, how to keep them burning: basic and now near-obsolete skills that I simply didn’t have. I was glad there were people to ask. The little iron holder stood there, odd-looking now but familiar for centuries, trash hardly to be counted when it was no longer needed. It stood there as the little iron representative of what can’t be listed on an inventory or a museum catalogue: the time of the rush harvest, the fat in the skillet, the hands that held the handle, the guttering light, the room it lit, the eyes that saw, the mind that knew.

In response I wrote a kind of list. I imagined a woman considering her own inventory, pausing over objects she knows will soon be sorted through by the administrators, summarily listed, priced, totted up. It began as a fantasy about how a few of the Museum’s holdings might have been owned and used. It became, like many inventories, a partial portrait. The woman in it has been a basket-maker in her working life, and she will appear more substantially in the book I am writing about local and rural histories. I am grateful to all at the Museum of English Rural Life who first invited me to think about the relationship between tangible objects and all the intangible things of which they bare the trace: skills, habits, repeated movements, smells, loves, associations.

Item: sundry goods in the outhouse (info here)

The brewing things. Everything smelt of the brewing. The washing smelt of beer until she draped it out over the lavenders and sages, and over the big rosemary bush in winter, and when it was wet outside the washing stayed beery. Wheat, barley, beans. The grain scoops on the shelf. The garden tools on their hooks. The churn. The butter mould. She had always liked turning the pat from the mould. There were two swans then: one on smooth sycamore with its gleaming brown wings, and the other on the butter. She used the edges of the butter first, leaving the swan intact as long as she could. Thomas, not noticing – why would he? – sliced straight in. It was only the containers that seemed to last: the butter mould without the butter, the creamer without the cream, the bread baskets without the bread in them, the warming pan empty and cold. You poured life into these moulds and patted it down and sometimes it took the shape – the butter had a swan, and the bread might be cross-hatched on the bottom with the pattern of the basket – but it was always the containers you were left with. You had to keep filling and filling them.

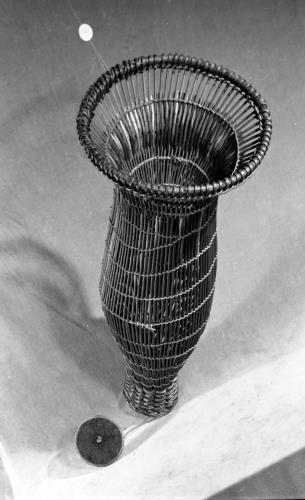

Item: dozen baskets (info here and here)

Grass, rush, willow. Big open log baskets, apple baskets, prickles; tight little seedlips worked so close they could almost hold water. Amberley trout in their baskets, each labelled, packed onto the coach, and onto the barges when they came right up the river. Long eel grigs too, when the trappers were doing well and could buy new rather than wash the mud out and mend their rotted holes. She used to have the feel of the eels inside as she wove up the walls, making the flared funnel mouth that would welcome them in and the shoulders of the bottleneck that would keep them. The space inside seemed alive as she worked, bodies flicking and sliding, thick and powerful.

She’d been the fastest weaver around for a time. Sarah and Hannah plaiting great long rush lengths for the coil baskets, held to the top of the doorframe so they could use both hands and pull the lengths tight, plaiting down and down. Sarah and Hannah on the verge in the sun, weaving all afternoon. In the wind and the frost too, sometimes, when it was better to be out in the light and the air even if your feet were damp with cold and the rods stung if they whipped back against swollen hands. Hannah unwrapping withies from the mellowing cloths and sorting them on the ground between them. In their laps, willow crosses became stars as they wove the basket bottoms and pushed in the stakes. The stakes rayed out from their laps until they were pricked up, one by one with the knife. A nick with the knife and the stake folded like an elbow. Hannah’s face seen through the upright rods, a bare coppice-wood growing up from her knees and waving far above her. Thick rods pushed and bent for the walling weave, pressed down hard. Then the siding weave, light and rhythmic, row on row. The tops of the stakes, waving above them, tangled if they caught against something and then swung back into their tall strange crown.

Item: pair of andirons

Item: treen, iron, lumber

Item: two joint stools

Item: two rush seats

Actually they needed new seats but she couldn’t start on that now. Twenty years they’d lasted: she’d done them when John was tiny. Beautiful hours those were, when he slept in the basket and she worked away. Snuffling sounds and fast little breaths all mixed with the rustle of the rushes as she took another length from the pile, knotted it on, twisted and twisted the two lengths over each other. Paper ribbons folded around each other until they were a fine cord, shining as she pulled it taught across the frame. Fold, fold, green against yellow against grey, the rushes pressed flat between her finger and thumb, the chair-leg held between her knees. She looked up, and – she could see it now – John was watching her, only his little head visible over the side of his basket, watching her intently, very round and still. She had cut a tiny lock of his hair and tied it to her rush, tucked it in among all the joins where no-one would see.

She would mend the chairs in the next life, if they needed doing. There would be rushes, she was sure of that. It was in the lovely and frightening passage they had every year just before Christmas, about what would happen, how springs would come from the sand, and the grass would become reeds and rushes. There was a sermon about it, every year just the same, but it was a good one. Isaiah promises that there shall be rushes in the wilderness, but here we have them already and give thanks. ‘A highway shall be there, and it shall be called the Holy Way.’ She felt herself walking out over the brooks, on the high dry path by the river, with the geese calling above her making their arrow across the sky.

*

You can find yesterday’s post, which contains further information about the Museum of the Intangible, here. Visit the Museum of English Rural Life website here, and follow them on Twitter here.

You can follow Alexandra Harris on Twitter here.