William Arnold’s Suburban Herbarium – a collection of one hundred photographic specimens of plants, which together form a homage to Victorian botany from the rear-garden cut-through, waste-ground, marshes and back-lanes of Truro’s rural-urban fringe – is just-published by Uniformbooks, and is our book of the month for May. Read Mark Cocker’s foreword to the book below.

At one level Suburban Herbarium seems a very simple book. Before you, over the following pages, is a series of one hundred plates of plants, grasses and ferns found on one small geographical plot.

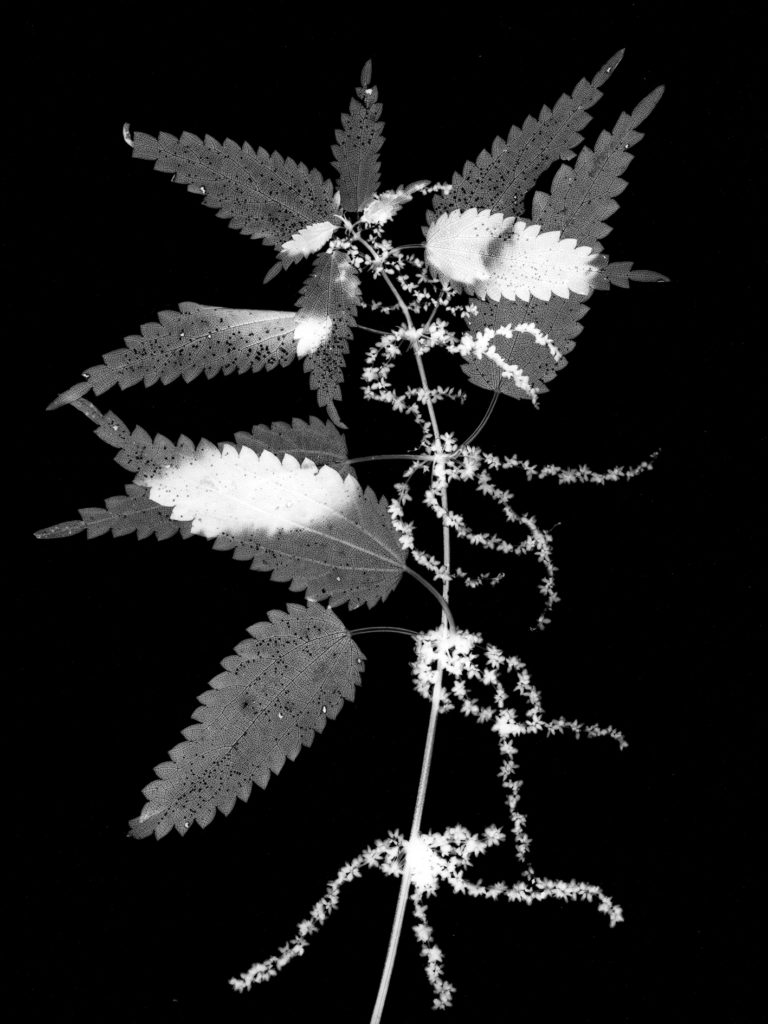

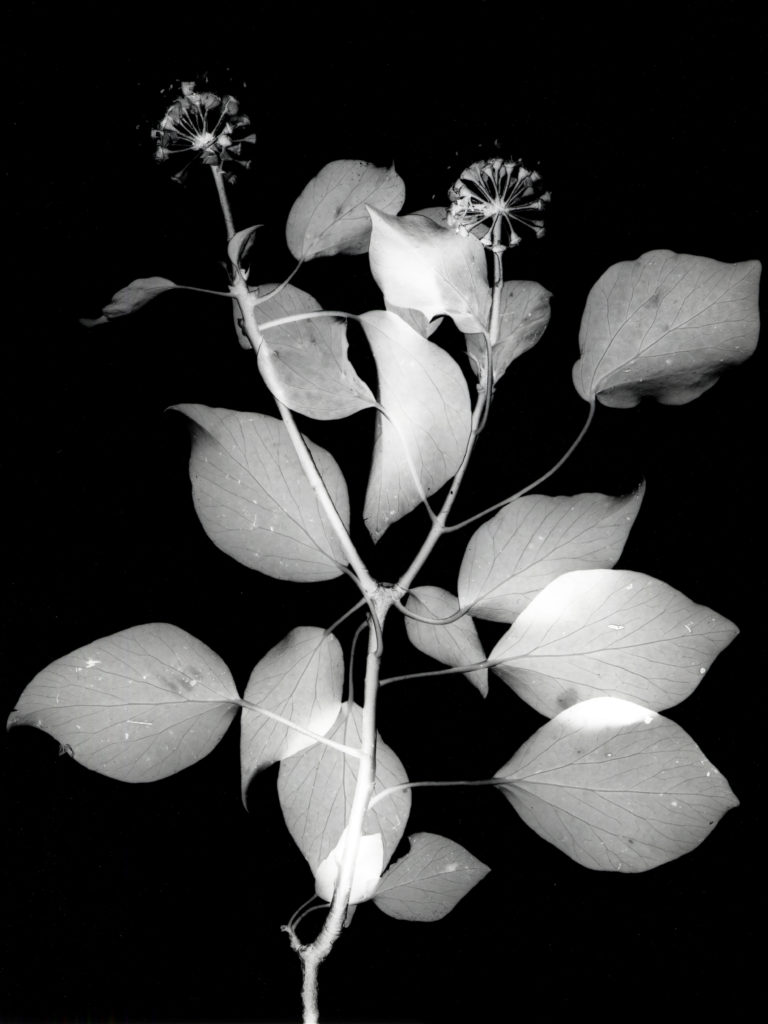

They are black-and-white photographic portraits but, if anything, they seem to convert their vegetable subjects to even deeper levels of simplicity. Instead of the minute details of foliage and flower that one has come to expect from digital macro-photography, here are the organisms represented as minimalist shapes of intense light.

One of my favourites is of hairy bittercress Cardamine hirsutum, (page 28) whose evocative name, as well as the plant it describes, is well known to me. I associate the species with deep black peat soils on Norfolk dyke-edges, where the tiny white flowers are washed by weak spring sunlight and blessed by the first bumblebees and orange-tip butterflies. Here is hairy bittercress, however, transformed to a many-fingered fire burning white hot in the night.

Turn now to perhaps the simplest of all of the images, that extraordinary plate on page 16. I know the caption says ‘Dutch Garlic Allium hollandicum’. To me the vision before you looks like nothing more than a supernova at a point of explosion, a fierce and impossibly bright light spiring into outer space in sixteen separate brilliant trajectories.

Looking at the photograph on page 51 I see that the caption says ‘Ash Fraxinus excelsior’. I have lived with ash trees as familiars and neighbours all of my life. They are the default species of Derbyshire’s limestone dales. That’s not an ash stem, surely. It suggests to me the image of a dinosaur’s four-toed foot—and look even at the detailed joints in the toes—from one of those little theropod species, whose proto-feathers eventually gave us the entire evolutionary lineage of birds. I could go on: the blackberry that suggests a firework display, the ox-eye daisy that’s a child’s drawing of our sun… but on a stalk.

As I look more generally at the whole collection, I am reminded of the words of two great philosophers. The first are from the French poet Paul Valéry, who once wrote “To see is to forget the name of the thing one sees”. What I assume he meant was that if we look hard and long enough at something then the physical processes of that genuine seeing will triumph over any presumed familiarities with an animal or plant. The organism will cease to be known and ordinary. The tired sheath of language in which we have trapped the subject will fall away and it will be revealed afresh in a new and radiant light. That is exactly what Arnold has achieved. He has made us see the plants as if for the first time.

Stinging Nettle

Urtica dioica

From the sublime to the ridiculous, I’m also reminded of those comic words of Dr Spock. As always, Captain Kirk would turn to his first lieutenant on the USS Enterprise for answers, and Spock would comb the air around the mysterious object with his weird whirring box thing, and then announce to his boss: “It’s life, Jim, but not as we know it.”

It strikes me that through the alchemy of his photographic practice Arnold has brought us exactly to this realisation. He has obliged us to visit a different planet and made us appreciate how weird and truly wonderful its inhabitants are. Weirdest of all is the fact that the planet is Earth and we have been here all along.

To be specific, Arnold’s otherworldly place is a section on the outskirts of Truro in his home county of Cornwall. It happens to be where he takes his lunch-time walk from his day job at Truro College. It is also the kind of overlooked, anonymous space that is such a commonplace feature of English towns and cities, what the writer Richard Mabey defined as being part of the ‘unofficial countryside’.

They are, in truth, neither rural habitat, nor urban district, but a hybrid zone where both coexist. For five years William Arnold has plumbed its unacknowledged depths and found and documented all the plants, grasses and ferns that have flourished there in the cracks between the pavements or perhaps along the edges to the walls.

The artist sees the plant citizens of this no-man’s land as overlooked in more senses than one. Not only are they neglected in the manner of the landscape they inhabit, they are also subject to what Arnold calls our ‘plant blindness’: our unfailing capacity to discount the significance of vegetative life in favour of vertebrate forms like ourselves. Just to give you a single powerful illustration of our plant blindness: the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds has 1.2 million members; its vegetable equivalent called Plantlife UK has 11,000.

European Ivy

Hedera helix

This indifference to wild plants is odd, especially in view of our disproportionate obsession with their larger relatives: trees. Just like those arboreal cousins, however, the herbs and lower plants play a central role in regulating all of life on Earth. Half the oxygen you will ever breath is delivered by phytoplankton in the sea that don’t even possess a nucleus, let alone a root system and a tree trunk. Arnold makes us think about this. All vegetation matters. We just prefer not to notice.

These haunting plates make us think finally about the artist’s own medium and practice. By presenting us with plants that resemble old-style negatives we are reminded of the very origins of photography. We are asked to recall how it was once a new technology that served as an adjunct to the scientific documentation of our physical world. These plates recall that history but they also subvert and comment ironically upon it. Here is a taxonomy in the grand manner of the nineteenth century, but recording a modern non-place and its overlooked plant inhabitants.

*

Suburban Herbarium is out now and available here in our shop, priced £14.00.

Mark Cocker contributes regularly to the Guardian and the Times Literary Supplement, as well as BBC Radio Four. His most recent book A Claxton Diary: Further Field Notes from a Small Planet was overall Book of the Year in the East Anglian Book Awards 2019.