Katherine Venn considers the debut collection from Robert Selby, which has just been published by Shoestring Press.

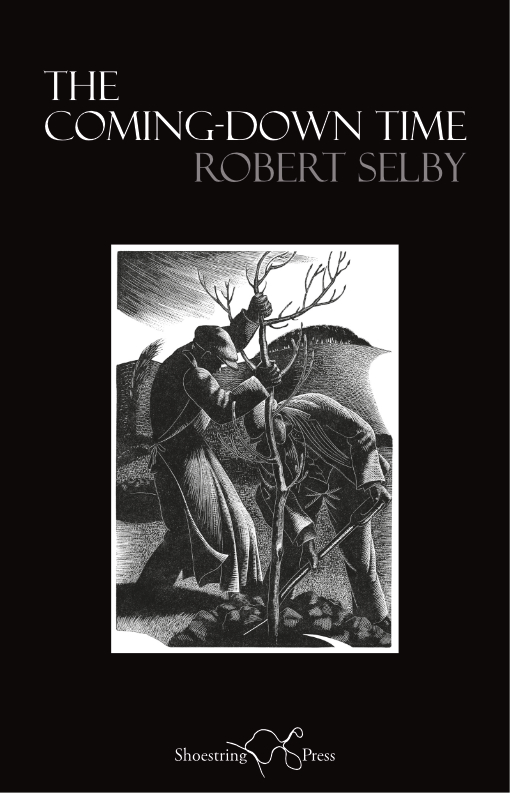

You get a taste of Robert Selby’s debut poetry collection The Coming-Down Time from the exquisite engraving on its jacket: two men in flat caps are planting a tree, a suggestion of wind or rain above them, a sumptuous tree-topped hill rising up behind and the black earth heaping up at their feet. There’s a suggestion of both delicacy and hard work, the richness of landscape and the toughness of working in it that could also describe the book’s contents, which begins with the description of a man – the subject of the first sequence – who ‘came from a long line of men who worked / now-extinct equine trades’, now buried with the ‘heaped-up past’ of ‘windswept grass’, leaving behind two dozen books, one with an inscription from that most stoic of Old Testament writings, Ecclesiastes.

This first poem opens ‘East of Ipswich’, a twenty-part sequence written in memory of two people who turn out to be the narrator/poet’s grandparents, in particular his grandfather – though this connection is only gradually made explicit. As with its opening poem the sequence builds quietly, its details subtle and almost spare, but such that by its end we feel we know this quiet man, the ‘intimate grit’ of his trade, his marriage to Doll, his experience in the Second World War: all of this the ‘heaped-up past’. It’s a beautifully assured blending of history and war with (auto)biography and a quiet lyricism, which feels quiet and understated – like the sequence’s main subject – and yet sudden gems flare in the poet’s hands: his grandfather filing only for ‘the narrow peace in which / to see his children and grandchildren grow up’; describing his death as ‘the soul’s release through the discreet door / in the great walled garden’. Delicately stitched together, the gentle accumulation of a myriad small details that zigzag between different parts of his grandfather’s life blossom into a tender portrait. This is a gorgeous sequence.

The second part of the collection, ‘Shadows on the Barley’, feels like a collection within a collection: poems that, as its title suggests, continue to be deeply concerned with landscape and time, and allow the poet to explore and expand on many of the themes of ‘East of Ipswich’ while taking them in different directions. We move from a wood where things are lost – the poem as a collection of objects, as with ‘XII Personal Effects’ from the first sequence – back to war; a landscape where a tree can absorb a bicycle; Jupiter’s moons; and sideways explorations of relationships and how they work, don’t work, falter, hesitate, are delicate and easily destroyed – and the devastating moments when we find we have lost what is most important to us.

Selby writes with a lovely, easy line that feels leisured and considered but never baggy or imprecise. As with the first sequence’s portrait of the grandfather, ‘Shadows on the Barley’ feels quiet and assured, with ‘a firm grip’, written in forms that feel subtle and making use of light rhyme. I had many favourite moments in this sequence but ‘Wild Cherry’ felt like it could be spoken in the voice of Doll from ‘East of Ipswich’, telling the story of a refusal to give up on a favourite cherry tree in the garden: ‘The day came when the wind chose to kill it’; but ‘you came from the garage with old rope / and lashed the tree by its waist to hope’. Perhaps this is how we all invest our hopes – in landscape, relationships, the power of poetry to memorialise, remember, praise. The ‘intimate grit’ of George and Doll is here ‘intimate compost’ that’ll be outlived by a tree –

The future unborn wouldn’t know what we’d lost,

but they’ll enjoy what we have heaved

on this rope like sailors to keep standing

in the gale …

Perhaps here we see hints of what one generation achieved for those coming after; they are themselves scarred in some profound way but send ‘rod-straight new boughs’ ‘skyward in corrective pursuit’ of being able to stand tall.

The third sequence, ‘Chevening’, seems to tell the story of a relationship through a stately home in Kent, addressed to ‘you’, and it was perhaps for this reason that I found it the hardest of the three sequences to get along with, somehow: it is intensely personal, so that I felt I was eavesdropping. But the same concerns shine through. There’s an intense preoccupation with place, the shadow of war looms, important journeys are made by train. Trees appear and reappear, personal effects are like the carefully placed objects of a still life, taken seriously in themselves but also speaking to a larger reality.

The tenth poem of the twelve that make up this sequence is a sonnet as measured and quiet as an English country garden and, perhaps inevitably in its first line suggesting to the ‘you’ that she has been shown ‘the real England’, feels like another touchstone for the collection as a whole: ‘a place of trees’ where history is a ‘link with others’, the railway appears again in a way that is both gift and entanglement. The sonnet’s sestet is as beautiful an invitation as any the collection has yet drawn:

Do you want to reset your watch to the toll of here?

Our years would lengthen into a summer’s evening

of wine on a lawn under bat flight. Then we’ll disappear.

All that’ll be left: two glasses filled with morning,

your silk scarf over one of the two empty chairs;

two lit candles in the church for us, if anyone cares.

An idyllic pastoral: but what is the romance that is being offered here? – a relationship with a person, or with a particularly English connection to domesticated nature, or with the rounding of the seasons, or with a casual posterity after death? This could be, again, George and Doll; or the lashing of a cherry tree to a post in the garden.

The devastating lightness of that ‘if anyone cares’ finds its full blossoming in the closing lines of the collection:

Now I must wait for the needle

of your heart’s compass to unspin,

and see where it stops.

And this is where I was left, too, feeling slightly on tenterhooks in terms of this sequence’s narrative, with the needle of my own thoughts having been taken in so many different directions in the same landscape. What an English collection, and somehow a very fitting companion to the times in which I read it: I began reading it on furlough in London, and ended it in Wiltshire at my parents’, just after the relaxation of lockdown rules meant that I could visit them for the first time in months. I actually read the final poems in the shade of a beech hedge, which felt appropriate, thinking about those wine glasses filling up with morning and the intimate grit of those we love and the places they themselves have loved.

This is a gift of a collection, where love for people and for landscape is expressed in a quiet kind of faithfulness and attention that’s enacted by the poems themselves. I look forward to more of Robert Selby’s writing.

*

The Coming-Down Time is out now. You can buy a copy, priced £10, here.

You can read poems extracted from the collection here.