It’s time for the annual end-of-year musings known in these parts as Shadows and Reflections. Since so many of our lives were lived in thematic overlap this year, we’ve asked our contributors and friends to focus on the small, strange and specific as they look back over the last 12 months. Today it’s the turn of Adelle Stripe.

One of the great discoveries I have made in the relative solitude of this year came from an aborted mission to Algeria, which was supposed to take place in spring. I had meticulously planned a journey to the capital, Algiers, and planned to travel east from there, to the Djurdjura mountain range in the Tell Atlas. I was already packing my suitcase when word came from the Algerian government that all flights into the country were cancelled, at which point my outlandish plans were thwarted.

As ‘Algeria’ had become my Mastermind subject this year, I devoted each spare hour to reading books on its history, the war of independence, or watching films, and reading its translated literature. When I wandered through Hathershelf woods in my hometown of Mytholmroyd each day, sheltering from pouring rain in wellington boots and fingerless gloves, my mind constantly wandered to that place I was supposed to be heading, rather than the one I was currently standing in, with its rotting leaves, knee-high bogs and vicious westerly winds that emptied their sodden contents above my head.

The primary aim of the road trip was to visit Maillot in the Kabylia region of north east Algeria, for a writing expedition with the Fat White Family. Lias and Nathan Saoudi’s family are from that area, so as part of the research I spent months learning about Algerian music, in particular the radical tradition of Amazigh singers and the more commonly known genre of Raï. Upon hearing that my flight was mothballed, I persevered with my voyage through Algerian music, as it provided the sense of escapism that I desperately needed this year. Through the lo-fi sounds that I accessed online, via Youtube or Spotify links, I imagined the landscape I could have been walking through – rugged pathways, deep gorges in blazing sunlight, cedar forests, olive groves and cherry trees – and the music transported me from the mizzle of Calderdale into those places.

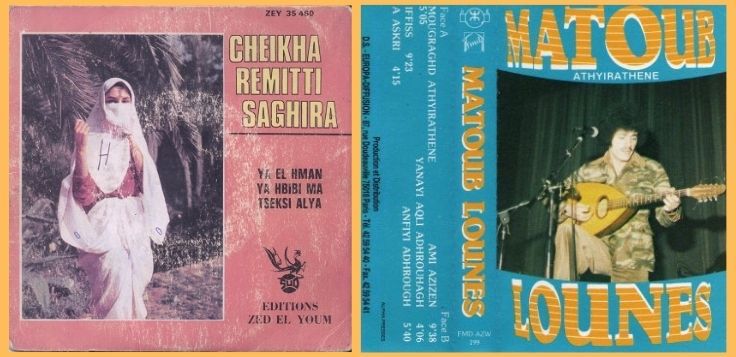

One artist I was really impressed by was Cheikha Rimitti, a female singer who performs gritty and frequently vulgar verses that resulted in her being banned from airplay in the 1960s. Known as the Queen of Raï, she once said that misfortune was her teacher, and that the ordinary and everyday struggles of women in the country, including poverty and sexuality, provided her with a wealth of material for her songs. When I first heard them, they reminded me of the dancehall records in my collection; there was a connection somewhere, perhaps in the rhythm and raw pulse. I felt invigorated hearing her sing, in the same way that listening to Sister Nancy or Lady G can often be. Like them, her vocals had that relentless, merciless execution of the line. It was thrilling to stumble across her.

Other musicians I unearthed from the Maghreb included Cheb Hasni, Khaled, Rachid Taha, Ait Menguellet, Mazouni and the anti-authoritarian, provocative, and legendary figure of Matoub Lounès, who was assassinated in the mountains of Tizi Ouzo. Listening to Andy Kershaw’s R3 show on Algerian music, I was struck by an interview with Kamel Baci, who believed that musicians from Kabylia are natural troublemakers, and that they always sing about politics, say the unsayable, and frequently end up in hot water for expressing their views. This tradition originated in French colonialism, when it was illegal for Algerians to speak disrespectfully against their rulers. For songwriters in this country, the essence of their craft is based in freedom of speech and opinion, something that was denied to them for so many years in the past. It came as no surprise to me that the cassettes of Matoub Lounès were frequently played in the Saoudi household, and that ten years after his death, the symbol that decorated his albums, a red crescent moon dripping with blood, provided inspiration for the bleeding hammer and sickle on Fat White Family’s debut LP, Champagne Holocaust.

I hope that at some point in the future I will reach Algeria, but in a strange way I feel as though I have spent time there already. Imagining a place can often be a potent replacement for physically being there, and I am grateful to have travelled through this country via its enthralling soundtrack this year. I have compiled a playlist for anyone who’s curious to listen to some of the artists I’ve mentioned, but I’m sure this is only the beginning of a longer sojourn into North Africa’s musical heritage.