It’s time for the annual musings known as Shadows and Reflections. Since so many of our lives were lived in thematic overlap in 2020, we’ve asked our contributors and friends to focus on the small, strange and specific as they look back over the last 12 months. Today it’s the turn of Dan Richards.

Last December, on the hills around Loch Melfort, south of Oban, I spent a long day walking with friends. There were dogs and the day was bright. Then it rained and the weather turned around and the sky tipped up, then cleared, and the sea out to Mull reappeared mirror calm — and there was good talk, and shared cake, and sore feet and thermos tea, and the low sun was honey — one of those days where you traipse home sore and ecstatic, feeling you’ve made the most of the light and earned your bath and beer.

And it was then that I looked at my phone and saw on the Guardian that Vaughan Oliver had died. Dear Vaughan. I knew he’d been ill but I’d never considered the idea he might die. He wasn’t the sort of man to die. He was big and rambunctious and wry. Not loud — I was going to write ‘loud’ but that’s not right. He wasn’t loud. He was ‘there’ — bull-like — forthright, sometimes. He often spoke very quietly, with bone dry humour, his work doing most of the talking. He knew his own mind. Didn’t know his own worth, always. He was doubtless stubborn but you’d have to be stubborn to create such a unique body of work. I first met him at a crossroads of sorts, he was getting himself back together — but more on that in a bit.

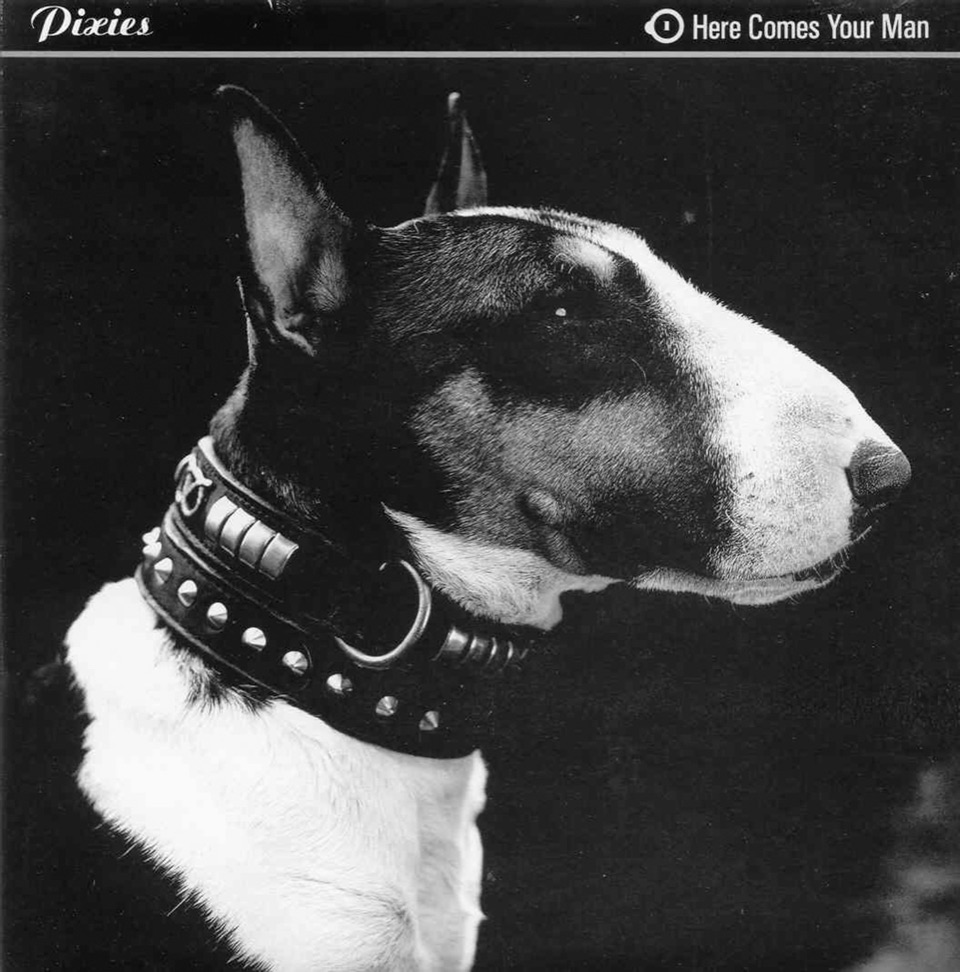

Dear Vaughan — graphic designer, collaborator, 4AD art director, pioneer, enthusiast, punner — many of his greatest records sleeves are visual puns — friend, proud Sunderland supporter — County Durham: ‘the land of the Prince Bishops’ he told me on first meeting. You’ll have his work in your house if you own any albums by Xmal Deutschland, Pixies, The Mortal Coil, Cocteau Twins, Wolfgang Press, Kristin Hersh, Breeders, Lush … He built studios and partnerships — 23 Envelope with Nigel Grierson, and v23 with Chris Bigg. Things fell apart. He rekindled his muse through teaching, talking; discovered he was loved and revered by folk around the world, started again. And, to be clear, the work was always great — often gorgeous, tactile, mysterious, unsettling, exciting and Vaughan himself was always… there. We met in 2009, at his home, an interview for a book. I had no real idea what I was doing, but he was kind enough to meet me anyway, and we got on. I returned several times, once with my friend Lucy Johnson who took some wonderful portrait shots — one of which the Guardian used in their story announcing his passing. Anyway, we stayed in touch. I once phoned him up during a World Cup — Spain were playing, a dead rubber, I think. ‘It’s a brave man who phones me during football, Daniel’ he observed with ironic awe. Yet he stayed on the line and we spoke — about what? I’ve no memory. Maybe I just phoned him up for a chat.

One of his final emails ran —

Thanks for keeping in touch with me during a challenging health period. Your book is both educational and entertaining. Can we hope for anything more?

You’ll have to explain the Scottish chapter to me as it seemed like peculiar punctuation in the scheme of things but then again you are a peculiar and charming fellow.

We never got to talk about the chapter.

His funeral was full of people who loved him. Bereft and disbelieving that he was gone. He was carried in to ‘Here Comes Your Man’. ‘Lust for Life’ was played. The eulogy mentioned a line from a school project about the North East, ‘there wasn’t sky in the cloud.’ His early promise as a sportsman, leader, joker, artist, writer. Academic all rounder. One off. And the puns / plays on lyrics — a big big glove of Gigantic, a line of gelatinous eyes aping the crossing on Abbey Road, the eels of Pod: ‘A male fertility dance in response to some very visceral music from an almost all girl band.’ The inversions of inside outside, the overlooked beauty of process — printer’s marks: crop marks, cutter guides, bleed and safety margins. Information as design. Spray paint on water. Patina. Broken glass. Buckets. At least, that’s what I was thinking, standing at the back; the surreality of all this. All his friends and colleagues here. His poor family.

And then we all filed out of the crematorium and got lifts of taxis to the pub — which seems so odd and decadent now; taxis with strangers, imagine. And then it was evening and we all left to catch trains, drunk on stories about Vaughan’s doings, imagination, humour, vision, way with words.

On the way out, I had a conversation with a man who turned out to be Jonathan Barnbrook about how he was going to walk across Epsom Downs at night in a thunderstorm, howling wind and rain, ‘no really, it’s best this way, I like to walk’ and off he went. And I turned and shook hands with Chris Bigg again and told him like I’d told everyone all day that I was so so sorry. And that was the end.

And all the way home I puzzled where Vaughan was now whilst rain snaked down the glass.

A few months later a Christmas card arrived from Vaughan. He hadn’t known my address so Lee, his wife, was now forwarding it on. It had a bear on it. It said —

Dear Dan,

have a good period.

Merriment,

Vaughan.

And I thought of Ravilious, lost in the seas off Iceland, his letters arriving home to his wife and family for weeks after the telegram announcing him missing.

And then, in September, I was looking to move flat and viewed a place filled with Vaughan’s work. The sellers had known Vaughan a little — the husband, Ewan, had worked in Rough Trade distribution, worked with Bill Drummond in his KLF days: ‘They said they were off to Japan and could I sort out something for Top of the Pops. I said… ‘What?’ they said ‘oh, you’ll be fine.’’ — and he’d been around the 4AD offices a lot. In fact he was looking maybe to sell his collection of artwork from those days, wasn’t it brilliant that we had this in common?

So Vaughan helped me buy a flat. I telephoned Lee and she said he’s helped lots of people this year — her, most of all — turning up, helping out, someone in common, creating introductions, continuing to encourage and collaborate from the great beyond.

Dear Vaughan — kind man, sensualist, collector, wabi-sabi devotee — I miss you hugely. The thought of you carrying on in the margins pleases me so much; as in life so in death — peripheral mischief.

*

Throughout 2020 I’ve thought of a story Vaughan told me about his dad. This evening, I went back to my tapes and found it, heard him speak it, wrote it out:

‘I think I’ve developed an emotional quotient over the years and that’s what I bring to a lot of work. I think I’m less prepared for upheavals than another man might be who knows how to steel himself for business.

I’m someone who has worked on allowing emotional response. I develop my emotional response in the work that I do. I haven’t cut it off and got on with business; and that’s a big thing to say and it might be a silly thing to say but I think I have allowed my emotional, poetic, artistic side to develop way beyond the business sense.’

What did your dad do?

‘He was a simple fella, a very simple fella. Where I come from, County Durham, the land of the Prince Bishops, the earth is underscored by amazing lines and veins of coal and mining. The National Coal Board. That was his work. He was a mining surveyor.

His neighbour told a great story about how, on my dad’s retirement, the neighbour made him go and play golf and he said, “Everywhere we fuckin’ went in County Durham, all your dad would talk about as we were walking up to the next green was what’s going on underneath.”

Man, that is so beautiful. He described the surface as a skin and all his knowledge was underground.

I said to him, “I’m going to scatter your ashes on Sunderland’s football ground,” and we’d just moved to a new ground called The Stadium of Light – which all the Newcastle fans make great fun of, obviously, with their poetry – but I thought, “All of a sudden it makes sense, The Stadium of Light.”’

*

Following the untimely death of Vaughan Oliver in December 2019, the publisher Unit Editions received a surge in orders for ‘Vaughan Oliver: Archive’, a book that sold out quickly during its original release.

Due to the many requests, and as a way of honouring Vaughan’s life and work, Unit decided to reprint a limited number of copies with a percentage of all sales donated to the Neuro Intensive Care Unit at St George’s Hospital, London, in acknowledgement of the care that Vaughan received.

The book will be republished as a single volume consisting of ‘Materials and Fragments’ (the original version included a second volume, ‘Remnants and Desires’).

Available at £59 with free worldwide delivery, you can order a copy here.