In ‘Plotlands of Shepperton’, Stefan Szczelkun documents West London’s improvised Thames-side architecture. John Grindrod reviews.

Some small books contain an incredible punch: a poetry collection, for example, or individually published short story. This small book, Plotlands of Shepperton, takes a different approach from those, but is equally as potent. This collection of photographs of relatively little-known interwar self-build homes along the river in West London, with informative accompanying text, works as an alternative history of the city in the last hundred years. This history begins in the aftermath of the First World War and continues through to today, and focuses on a version of London designed and built by working class residents whose story has been somewhat erased from history.

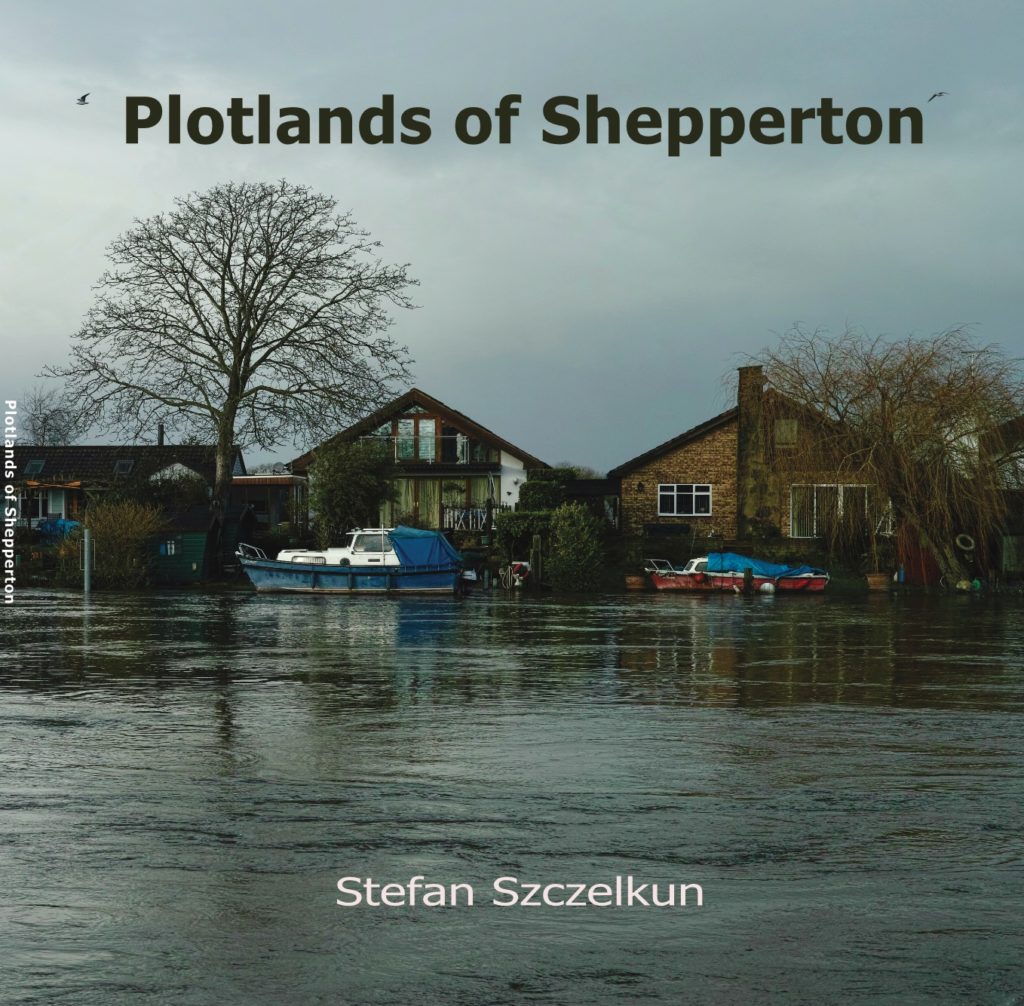

Plotlands are a working class architecture, born out of the post First World War Homes for Heroes ethos. While developers took a lot of the prime sites around towns and cities and along transport corridors, working class folk bought small plots of land, often in unwanted areas on flood plains, along waterways or near the coast to build their Plotlands settlements. As Szczelkun explains, these homes each begun as ‘a “flat-pack” chalet, old railway carriage or a showman’s wagon that had seen better days’ before being extended and modified over the years as needs arose. The resulting homes are free from the sense of middle class propriety that governed the design of local authority housing or the pattern book homes of the big housebuilders. They are exuberant, eccentric and prone to ingenious modifications and workarounds. But because of their anti-establishment origins they also lack protection by planners. Many of the originals have been destroyed and replaced by more conventional houses, and more recently, huge Grand Designs-style constructions.

This is a short, small, square book, most pages taken up with photos of Plotlands houses with useful captions. Images range from those taken in 2004 on a Sony video camera to more panoramic shots taken up to 2016. As a piece of suburban social history, a record of a place and a way of life it is a hugely valuable piece. In the layout of text and captions there is a similar sense of freedom as the Plotlands themselves, rather than the whole being resolved in a more tasteful, minimal style. Szczelkun trained as an architect in the 1960s and was later part of the improvisational Scratch Orchestra, whose freeform expression seems to have struck a personal chord at least as deeply as his architectural training. This book is in some ways the child of both interests, taking delights in architectural forms that resist the uniformity of mass production and municipal design.

Szczelkun carefully shows how officialdom became threatened by these outcrops of working class making, and how that influenced the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act, outlawing these kind of unplanned homes. The book presents the amazing variety of houses, from simple prefabricated bungalows to chalets with verandas, in all sorts of configurations and states of repair and renovation. There are colourful excursions too, taking in Shepperton’s most famous son, J.G. Ballard, his sturdy and very un-Plotlands semi-detached house, and the lurid violence he visits upon the locals in his novel The Unlimited Dream Company. And then there’s the film studios, immortalised in Matthew Sweet’s book on early British cinema, Shepperton Babylon. Taken together these three books present Shepperton as a kind of Wild West London, in a way that it is rarely spoken of. These disreputable portraits of an otherwise sleepy middle class enclave remind us that our cities are complex machines, and that curiosity, absurdity and surprise lurk around every corner.

As we enter an age where planning rules are being ripped up it will be interesting to see who benefits — the big housebuilders, whose huge operations have hampered the success of small and medium size companies, or individuals attempting their own self-build projects in the spirit of the Plotlands. Despite relentless government rhetoric these last forty years about the importance of private enterprise, it seems unlikely to be the dawning of a new golden age for working class self-builders and new Plotlands — and so we must protect the ones we have, and prevent them from being gentrified and made ‘respectable’. This book is a valuable record that should help us understand them.

*

‘Plotlands of Shepperton’ is out now. You can buy a copy direct from the author here.

John Grindrod is the author of ‘Concretopia’ and ‘Outskirts: Living life on the edge of the green belt’. You can follow him on Twitter here.