Keith Vinicombe’s ‘Birds of Chew Valley Lake: Ecology, History, Tales’ causes Tim Dee to look back at his own formative relationship with Chew Valley’s waters and avifauna.

Forty-plus years ago when birdwatching south of my home in Bristol at Chew Valley Lake – specifically a week or so counting ruff and other migrant waders in the early autumns of two years in the mid 1970s – my teenage self was delivered to a kind of meditative yet febrile ecstasy. The experience I had of watching those birds at that time in that place – the active state of attentive immersion in the specifics of nature – could more generally describe how, ever since then, birdwatching, at its best, has been for me. Now, a new book has brought those formative days back: days rinsed fresh again in my memory, spots of time that shine still. And I have learned from its pages how much of the since-then-persisting-me was made then, in that place, with those counted birds, and in the company of those who were also counting.

CVL (as I still think it) was then (and still is to me) synonymous with KEV. Keith Vinicombe’s initials (I’ve never known what the E is for) followed almost every telegram-style report from the lake that were listed systematically (divers and grebes first, etc.) in the monthly roneo’d bulletins of the BOC (Bristol Ornithological Club). I consumed these sitting up in my bed night after night through those years. And, if I hadn’t eaten enough at these midnight feasts, I’d take the foolscap pages to school the next day and continue – illicitly – tapping their nourishment. There were records from all across the BOC region, but the birdlife of Chew was what I most wanted to read about because I had started going there. Keith counted almost every species at the lake and almost always had seen more birds in bigger numbers than anyone else.

This book, written by him with John Rossetti (another local hero of my youth, and one of many birdmen at least part-fashioned, like me, by the Field Club at Bristol Grammar School), draws upon those records and counts (and record counts). It is a great compendium (468 fully illustrated pages) to the past and present birds of Chew. That the lake is still known as a good place for birds is chiefly, I think, because of the quantity and integrity of Keith’s observations. He has worked its water and its shores for more than fifty years and they’ve given up to him almost everything avian that they’ve had. There are other keen birders now, of course, and there were too, but I think him long installed as the presiding bird-god of CVL. Keith would say his book is made from much more than just him and his sightings, and it is, but I am certain that there would be no CVL in bird-people’s minds if there had been no KEV. Perhaps (as, for me, it turns out too) there would also have been no KEV without CVL.

I’ll mention one other holy-man. Before Keith’s time, there was a famous pied-billed grebe at Chew, the first record of the North American bird in the Western Palaearctic. Robin Prytherch was among its finders in 1963. The logo of the BOC is that bird. It was drawn, I think, by Robin. The tiny creature returned to either Chew or nearby Blagdon Lake for several years until 1968, when it was last seen, calling (in vain) for a mate. Robin heroically tried to teach me (in vain) bird ringing at Chew (I wrote a little about this in The Running Sky) and has, also heroically, undertaken the longest study of buzzards in Britain, if not the world, based on his observations of the birds that can be seen from the split-level section of the M5, just south of the bridge over the Avon. Perhaps you’ll remember that the next time you take the road – I do every day that I drive that way. The word amateur is derived from the Latin for lover. Bird-people, even bird-gods, don’t talk of love very often or how it figures in their hobby, but if you know to look for it, you can see it nonetheless. Robin was still active when I first opened this book; he died this week when this piece was being finalised.

All local avifaunas (county-level volumes are the norm, site specific books like Birds of Chew are more rare) are necessarily vital for those who contribute to them and to those who subsequently use them. They tell the truth as to what was and what is and what may yet be about. ‘Much about?’ is the greeting call of many bird-people on meeting others already working a site. Books that are assembles of what has been about are bibles for birdwatchers, bibles and missals and almanacs, and news bulletins and yellow pages and dream-diaries. Birds of Chew Valley Lake is not so different from many such publications, but for me, because I know the place, with the book to hand, from this time on, it will always sing the loudest of any and the best.

It was always a treat to meet Keith at Chew. It was a break from birds, though our talk was all about them. He never seemed to be birdwatching when we bumped into him on Herriott’s Bridge or at Heron’s Green. He was happy to chat. Sometimes we all had ice-creams from the van that parked on the bridge. I was one of three walking around the lake; he was on his own with his motorbike. He was always friendly and interested to hear what you’d seen. He would raise his binoculars occasionally as he spoke. He had a stammer that seemed to ease when he was looking elsewhere. I suspect he’d already spotted everything we reported but he never said anything that would crush our enthusiasm. He laughed a lot too, and, after hours of whispered monosyllabic listing talk between us three earnest teenagers, to meet Keith always felt life enhancing and life enlarging. I remember an unprintable but electrifying vulgarity he coined about the difficulty in separating dusky and Radde’s warblers. Birds, as talked in his company, were part of the wider world and a way to know that world, too. I loved finding that out by listening to him. He was as serious as us – in fact, far more, but he forever played down his seriousness. (He went on to serve on the UK Rarities Committee and wrote new-era game-changing identification guides as well as finding incredible rarities.) Fifteen years ago, entirely by chance, I met him on a summer’s day on the coastal path in Pembrokeshire where we were both watching choughs work their black magic in the vortex of a cliff-edge updraught. We identified one another from a distance through our binoculars, as bird-people will, and we laughed once again. I’ve hardly been properly birdwatching at Chew since, but reading Keith’s book makes me miss it and him.

*

I’m not much younger than the lake and I’ve known Chew, on and off, for fifty years. I have drunk its water for most of my life. I fell into the same drink once, slipping down a bank to be muddily baptised in Heron’s Green Bay. I was looking at some distant wader and lost my footing.

It is called a lake but Chew is actually a reservoir. It was constructed in the 1950s and supplies water to the city of Bristol ten miles to its north. At the north end of its 1200 acres, a concrete dam and outlet tower with sluices, spillways and pipes sees to all its onward watery business; otherwise Chew’s shores are natural and the lake isn’t deep. Farmland runs to the water’s edge. In a few places like Herriott’s Bridge and Heron’s Green Bay a current road comes close to the shore and crosses the fringes of the lake via a bridge or a causeway. There is one, wooded, island that we walked out to often in the dry summers of the 1970s when the water shrank away. The fishing is good, stocked trout mostly, but there are pictures in the book of colossal pike. There is a sailing club too. It’s a reservoir like many others, but is also one of the best man-made landscapes for nature in southern England.

What lies beneath the water today was once more of the same ground as its current banks: mixed agricultural acres, cows and corn. There are some, now ruined, buildings and old roads down below too. Low water levels in dry times expose drowned stonework. In those parched birdwatching days, forty-plus years ago, the sunken world often ghosted and shimmered in the heat-haze on our walks around Chew. Did I see then, or did I dream, a church tower?

If you have a Bristol Water permit you can access some birdwatching hides on the lake edge but no complete circumnavigation of Chew’s shore on foot is allowed. Not officially, at least, but for several years in the mid and late 1970s I spent many days doing just that. With my two – more committed and knowledgeable – friends, Antony Merritt and, my cousin, Tom Nichols, I went again and again to Chew. The concept of a local patch for birding didn’t exist in those days (most people only went birdwatching locally), but Chew was that for us. We all lived in Bristol. Early in the morning of many weekends and through every school holiday, we walked to the city bus station from our homes. The first bus was the best to get. Usually, we were already wearing our binoculars as well as wellington boots and anoraks. The bus took us out of the city, over a first run of green hills, and down to the villages of the Chew valley and the promising shimmer of water. We got off and continued on foot to wherever we were starting that day (the time of year, the level of the lake, the weather all determined our route, with Antony pretty much always deciding what that was to be). We all had notebooks and, as soon as we reached the shore, we fell into a kind of observant silence and started looking: identifying, counting and noting. It took all day to get around; at times, if the birds had detained us (Antony in particular could not be torn from an unidentified something or an unvisited mud patch), we had to run for the last bus. Only then did we add up our totals and start talking of the day. Perhaps Antony and Tom made more spoken sense of it at that time than me. I had loved it physically as much as anything. Being in the same space, and beneath the same weather, as sixty ruffs in the course of eight hours, had exhilarated and exhausted me, and often I fell asleep on that homeward bus journey, my teenage chin, bum-fluff and all, branded with the circular impressions of my binocular eye-cups. Many times we did the same walk the next day. I make it sound like a pilgrimage to a holy place, and I think it was – a telling of our times with the birds – though, then of course, we would never have put it like that.

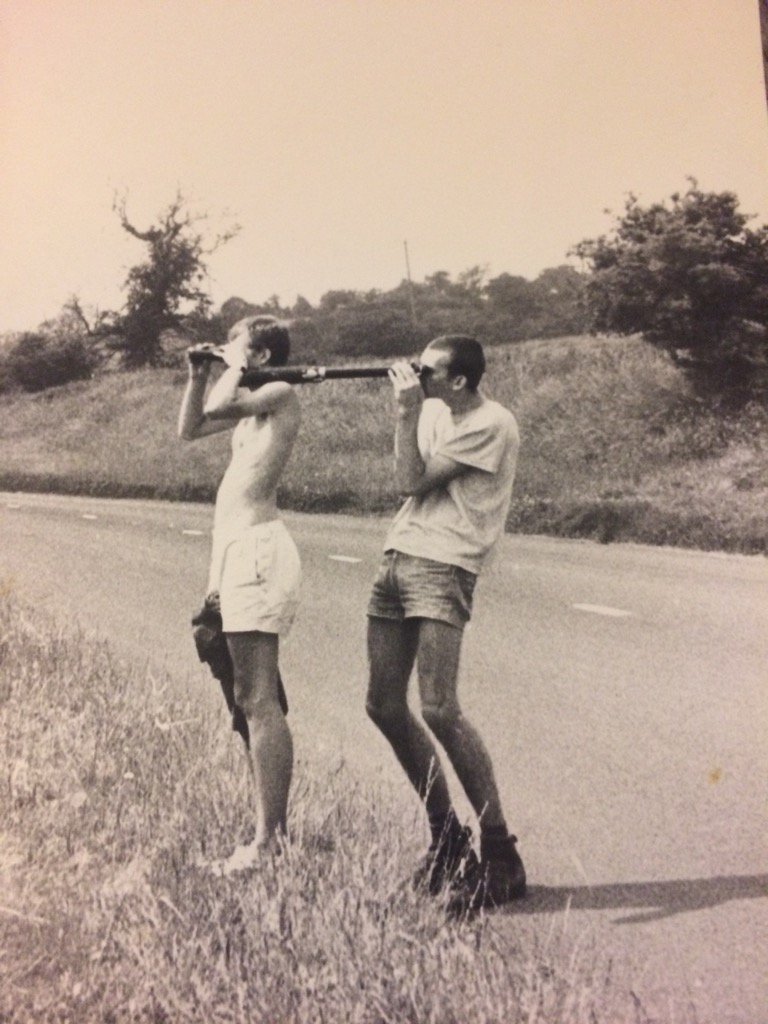

Tim Dee and Tom Nichols, 1977

Rather, I learned what to look for in a migrant sandpiper wading the shallows, the jizz of the bird that pulled a green sandpiper to the left of a common sandpiper and pushed a wood sandpiper to the right, the teetering call of a escaping green, the spirit-level of the bobbing common, the décor and decorousness of a wood. So did I grasp the measuring stick that would keep a little stint from a dunlin. So was I schooled in the wing bars of ringed plovers and their absence in little ringed plovers, and in the getaway flights of greenshank and the swimming skills of spotted redshanks, and the calls in the mist of moving golden plovers, and the diversity of birds that must all be labelled ruffs. And the same for roosting gulls and passing terns, and eclipse plumage ducks, and winter divers, and scratching warblers in the reeds and seeping pipits in the grass. I ate each day’s packed lunch on the bus as soon as we left Bristol. After that it was just birds.

The lake sits cupped in the last vegetable-green acres before, towards the south, the Mendips (some say just Mendip) haul up their (its) more tawny-skinned and stony hulk. Chew’s water comes from these limestone hills. For me, on my teenage mental map at least, Chew belonged to Bristol, where its water went, while the Mendips formed a rim to the rest of the world that was not my home. Elsewhere began there, and its places still have distance inscribed in them: the heathery heave of Black Down which is good for midsummer nightjars; the pale bony rock terraces at Rowberrow Warren with blue butterflies and hobbies and grasshopper warblers; the caver’s pub at The Hunters Lodge, with cave access just beyond the car park; Priddy Pools and Stockhill Plantation where there were long-eared owls, with their owlets making squeaky gate calls from the firs; the black obsidian-shiny lead slag heaps at the mines at Charterhouse and Velvet Bottom where spring redstarts can still be seen, matching that shine; Crook Peak which keeps snow longer than anywhere else and lures migrant ring ouzels most spring and which still fuels a dream, refreshed every year, of a trip of dotterel; back to the east is Ebbor Gorge, hidden away like a secret land, and Cheddar Gorge, where, with potent geologic justice, a vagrant wallcreeper came to run up and down a quarry cliff for two years in the 1970s, describing for me (before any bird had at Chew) the far-out thrill of rare birds; and, then, then, looking to the view, south of the hills, that pulls at your eyes, the far-spreading levels, their wild species of grassy sea made from a wet and peaty land, magically untamed in its spongy horizontality.

That is all beyond Chew, and because of Chew such places are now always further away from me, wherever I am. Although I’ve hardly been to the lake for decades it remains close, an adjunct. Ever since I first went, I have thought of it as something like a place just beyond the bottom of my garden. I remember being stuck in class on schooldays (with or without my bird club bulletins) and working out, relative to my desk, where Chew was, and then, instead of attending to my simultaneous equations or essay on the Reformation, looking towards the water. That kept me going. I lived off my knowing of the place then, and now, I find, I still am.

For a time our trio all had telescopes as well as binoculars. Most of our kit was pretty hopeless. I had what was actually a toy – a one-foot long so-called astronomical telescope, silver and shaped like a rolling-pin with a tiny eye-lens. I took it out with us once and tried holding it up like one half of a pair of binoculars and saw nothing that even a pinhole camera would recognise. It never left my room again. Tom had been given an old naval telescope; a brass draw-tube affair which, if subtly adjusted (to use it felt like you were grinding your own lenses right then), could achieve perhaps twenty-times magnification. Its three (or was it even four?) sections had to be extended, and it was best used when prone, with a crooked knee doubling as a rest for the object lens. Many birdwatchers at this time were first met in such a position; you might identify heroes by their angle of incline and the cut of their knees. Befitting his status as the most experienced of our boy band, Antony was the first to get anything optically decent: a Bausch & Lomb or Hertel & Reuss Televari (I can’t remember now and Antony cannot be easily asked). It was black and serious and managed up to sixty-times magnification, I think. Still, though, in those days there were no tripods; wobble and shake threatened all clarity of purpose. The best option was a motionless and uncomplaining junior shoulder that might be recruited as a steadying surface.

With Tom contorting himself horizontally in the wet lakeside vegetation, I stood heron-like, stiff backed and stock still, while Antony rested his telescope on my shoulder and scanned the shore. I tried not to sneeze or scratch; I tried not to breathe. Cumulatively, I must have remained like this for at least a day of my life, perhaps two. Antony used the telescope with intensely silent (and uninterruptible) concentration, working right to left and left to right, magnified inch by magnified inch, panning the muddy edges and the water-plants for ruffs and green sandpipers and other waders, or peering further out, searching the centre of the lake, where black and other migrant terns and little gulls jinked and fluttered above the sloppy wavelets in the hot wind of the early autumn. I already knew Antony could hold his binoculars to his own eyes for longer than any other human; using the telescope he beat his own record. I might have learned to meditate then as I stood and looked ahead, blankly without focus, to where Antony’s lens was also pointing, it taking in everything, me emptying myself of anything, yet with something of the occasion going in, and me heavy-lidded, now, craving sleep, while the midday sun scorched my wind-battered face and biting flies came, undeterred, to drink at my running eyes and cracked lips. “Another ruff”, Antony would mutter, eventually, by way of decompressing, as he straitened up and looked where the telescope had looked, coming back to the unmagnified Earth and into our shattered company.

You had to be there to see anything, for sure. Now anyone could know what is at Chew pretty much as it occurs and look it up online and be delivered to a virtual bird. Pictures come to me in South Africa of an osprey seen in the last hour at the back of Herriotts’s Pool at the lake. I know what’s about from thousands of miles away. In my early bird days, only those who were there knew what there was to see. Anyone else would have to wait for a month when the BOC bulletin arrived in the post. The club provided record slips and I filled some in every month (Antony was our note-keeper-in-chief when we were a trio but sometimes I went solo to the lake with my dad on a weekend afternoon and stole an observation or two). In a cupboard in the bat-cave of my stuff in Bristol, I still have some half-finished slips from the back end of 1970s that I never submitted. By then Chew was just beginning to dim a little. Punk rock and existentialism were beginning to get in the way. I took to wearing a blue plastic toy gnome on my raincoat even when birding; cousin Tom started playing bass for the Glaxo Babies. The ruffs were still there (though they aren’t so much these days), but we went less often to be with them. Chew was never quite the same; but it and its birds had done their work (which is not theirs at all, of course, and is magnificently unknown to either) and everything that has followed for me has somehow followed us teenagers tramping around the lake’s watery margins and counting its temporary holding of ruffs and others.

I have many other Chews saved now too: from Moreton Hide, I watched the winter gull roost for a couple of years and, if Keith was there (which he often was), there was a chance in the last minutes of a short December day to tease a ring-billed gull from the thousands of common gulls arriving to sleep on the water. (When a student in Swansea, Keith had identified the American species several times in South Wales and put the bird on the British map as much as anyone – he was a guller long before anyone used the term). I have also watched other lost birds doing their best at the lake – two long-billed dowitchers muddying up together by Herriott’s Bridge, a citrine wagtail dowsing the wet fringes at Heron’s Green. In that same gull-roost hide, I saw for the first time in my life the mid-air mating of a pair of swifts on one calm evening one mid-May; I don’t expect to be granted another sighting. In that hide, I recorded a play for BBC Radio 4 written by the poet and sometime birdman Paul Farley; it was about a runaway felon seeking sanctuary and not expecting to meet two birders who were getting rivalrous over their duck counts; unsurprisingly, it was called ‘Hide’. I took girlfriends to those same wooden rooms on stilts and nothing happened, except that I don’t know them any more. I took the toddling versions of my now grown-up children to the same creaking places and had to shush their toddling enthusiasm when other bird-seekers came in. I took my elderly and infirm father there, decades after he first took me when I was a schoolboy, and I had to help him walk up the walkway and to focus his binoculars.

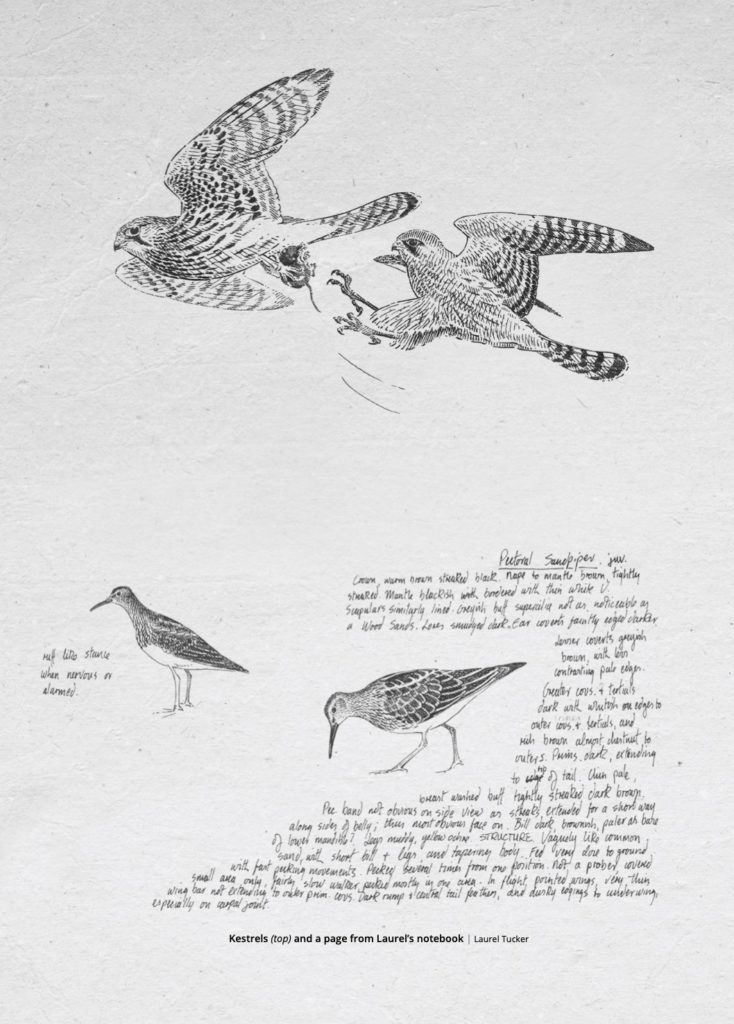

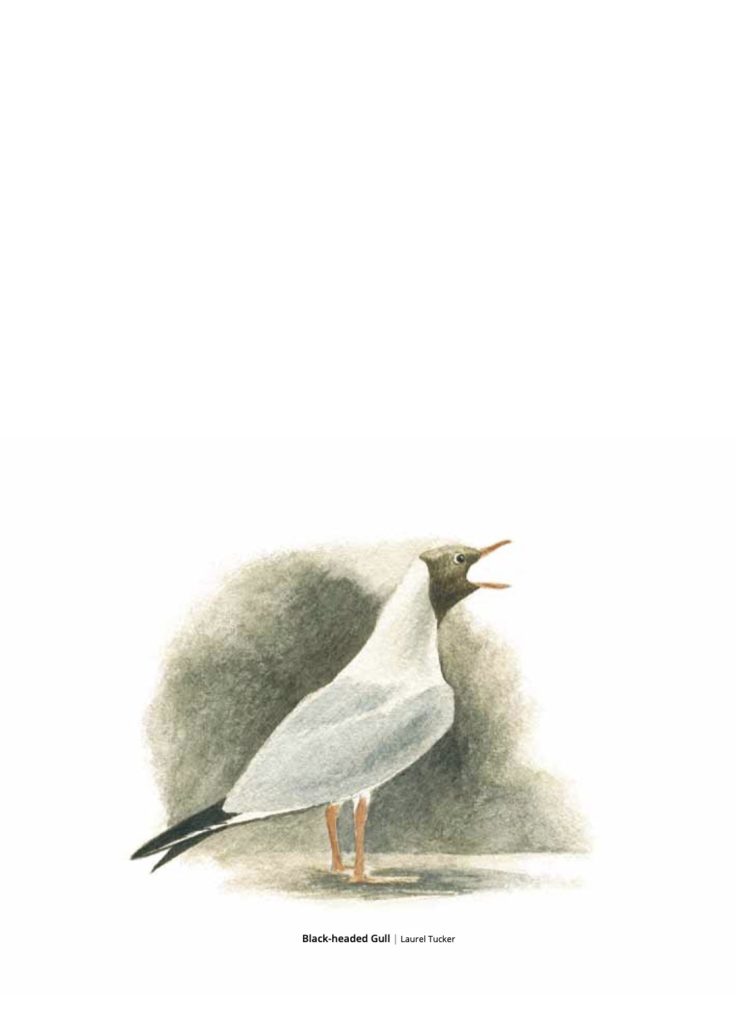

Today, Antony is cruelly sick and bed-bound, and Tom lives away in Glasgow; more recently, my Chew companion most often was another Bristol bird friend, the artist Greg Poole, but he is dead now. I also knew his friend and fellow artist, Laurel Tucker, and met her sometimes at the lake. Dozens of her pictures light up Keith’s book: she was his partner until, still only in her thirties, she died. Decades after I left school, I met Derek Lucas once at Chew, my former English teacher and the leader of our Field Club, who was among those who set me going on my lifelong and sustaining dual feed of birds and words. I wish I had told him that, but I didn’t and he is dead now, of course, too. Another day, I wept in every hide on one lonely circumnavigation after my relationship with the mother of my big boys ended. And, around the same time, in the ringing hut at Herriott’s, under the auspices of Robin Prytherch, I lost my grip on so many reed warblers such that I knew I was not to be a bird-ringer. There’s no keeping any of them, it seems, however you close your hands around their bodies. Today, I hope that a son of mine (there’s a third now, marvellously small still and a stranger as yet to Chew) will, one day hence, nip over a fence, at a quiet spot somewhere on the lake perimeter, and pour a little of the dust of me on the water, like pepper on a soup. I’d like that.

*

Birds of Chew Valley Lake is available from www.NHBS.com and www.wildsounds.com. And also, until the end of March via https://tinyurl.com/ChewBirds where it costs £24.95 with free P&P (UK only).

Tim Dee’s Greenery is published in paperback on 25th March. Trapped down at the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa, he fears he is about to miss his book’s launch (for the second time) and the European spring too (encore une fois) that it is all about.