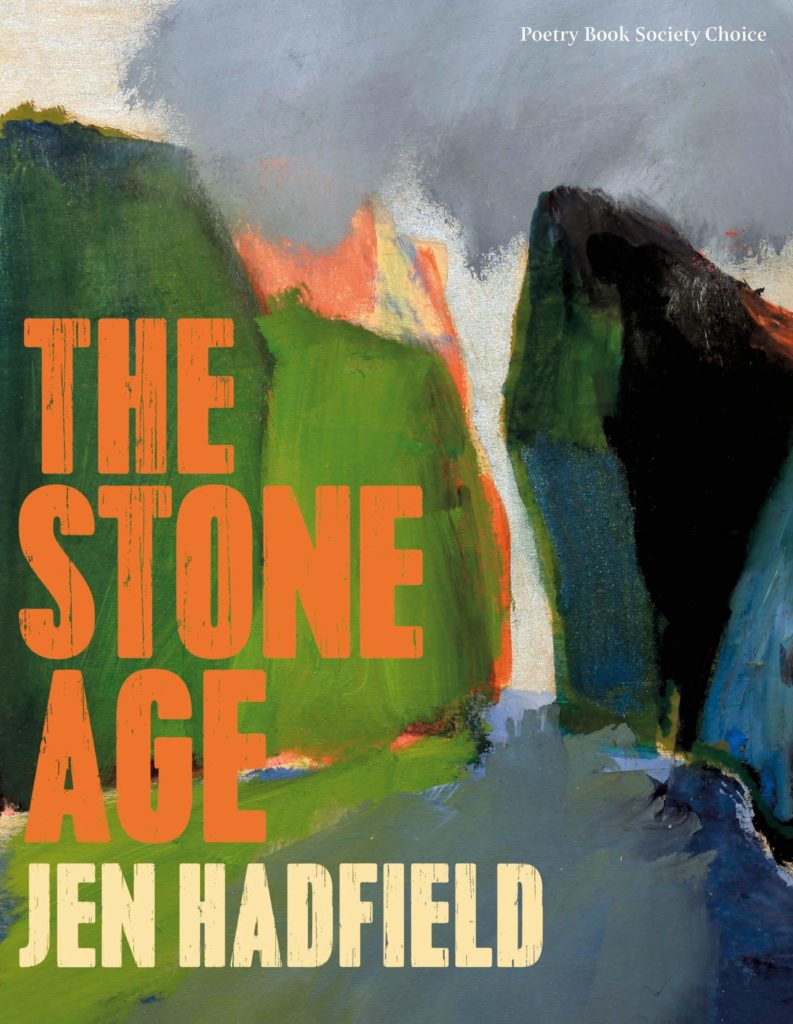

Jen Hadfield’s ‘The Stone Age’ — a depiction of the wild landscape of Shetland, as well as its people and their working lives — is just-published by Picador. Blue Kirkhope reviews.

Returning from a walk across the bog in the valley I now live in in Shetland, I kick off my dirty boots and empty my pockets of seabird feathers and blue-tinted mussel shells retrieved on my afternoon exploration. I have been retiring to the pages of The Stone Age in the quiet hours of this new life of mine, and have been carrying newfound perspectives from this book out there with me since it landed through the letterbox of my new ‘Z’ postcode, the feathers and mussels now bearing a whole new weight of meaning. It has been a joy getting to know these landscapes these past few months, and having Jen Hadfield’s writing as company only enhances it.

Hadfield’s poetry has always evoked her love and curiosity for the natural world, but this new collection of writing tells us so much more. Shetland, and all of the life that comes with it, takes to the stage; the place, its wildlife and community pinpointed on the map. The second poem ‘Hardanger Fiddle & Nyckelharpa’ is a beautiful homage to instruments commonly used in traditional Shetland folk music, ‘enough to touch the nerves of the North’. The poem ‘Scythe’ refers to the people and their dialect, a touching scene in a garden setting:

‘It sounded like you said a sigh –

in the Northern countries,

to say yes is a sigh – a

kind of swift, indrawn gasp’

A few pages in, written in large bold text, is the sentence ‘to gawp out through my Northern pane’, and the exciting and intricate poems that follow – especially those which give inanimate objects the ability to think and speak – are enough to make anyone gawp indeed. Hadfield’s bestowing upon the non-verbal, non-human the power of consciousness is one of the most alluring aspects of the book; we are given the perspective of a nudibranch sea slug in a rockpool – ‘each breaking wave dousing me of costume, comfortably, divested of my name’ – and a cliff reflecting upon its very own existence: ‘Bits fall off – it happens all the time’. This way of thinking is infectious, a whole new way of seeing. To personify nature is to better understand the natural world; an urgent prompt to take better care of it – because if our sea slugs and our cliffs had the ability to communicate with us, then surely we would pay far better attention to them? If there is anything that has been brought to our attention during the nature conversation over these past few years, it’s changing your perspective; confronting the oohs and aahs of nature that have been perfected through the lens of an Instagram filter and seeing nature for what it truly is. Hadfield has previously been branded as an “eco-poet” and I really feel the worthiness of this title throughout the collection.

You may be mistaken to think that Shetland itself is the centre of the book, but neurodiversity appears to be the very root of its existence. Upon first read the typography of the book caught my attention immediately, often roaming through enlarged text. There is a poem called ‘Drimmie’, where the ink of the text slowly fades, perhaps illustrating the light in the ‘fleeting moment in the quality of dusk’ Hadfield speaks of. There are gaps between the pages; fragments of text and symbols; some poems concluded in an open-ended manner, leaving the reader free to interpret. Towards the end of the book, sometimes there is nothing on the pages at all. Not only do these pages make me feel as though I’m navigating through the very landscape itself, trudging across spongy sphagnum moss, clambering over the barbed wire fence of ‘Strom’ and across pebbled beaches, but that I am navigating too the fleeting moments between thoughts; the spaces, the different-sized text, all signposting us to the pace of a neurodiverse mind. Sometimes, between poems, large text is structured in brackets. ‘…While you press me for an answer, I’m still considering your first question’ Hadfield says, and later ‘because my sentence is lava slow and sometimes mangled’ – a nod to the pace of the poet’s own words and thoughts. With this comes sheer power, vulnerability and intimacy – incredibly admirable when we can so often dilute our own experiences, sacrificing our truth so others can better understand us.

That we all navigate ourselves through this world by walking, talking and thinking differently is something of which Hadfield continually reminds us. ‘The problem is the yoying, Beyond your hill-buddy vanishing in three swift strides’, she writes, highlighting that when we are out walking with someone, they are experiencing the landscape in a completely different way to ourselves; perhaps your gaze is fixated on the seabirds and the horizon, while the person next to you is on their knees, inspecting the flora, or perhaps they find joy in bounding over the hill at lightning-speed while you would much rather take your time. The heart-warming poem ‘Granny whose gaze’ also speaks of how we perceive and experience things differently; ‘I don’t like to see the new moon through glass’ declares Granny. Acknowledging, communicating and sharing our differences – to ‘leave your footprints in my wet meadow’ as Hadfield puts it – can only enrich these experiences. By challenging our perspective, pace and proximity is to experience nature at its very fullest.

Whether we do so through talking to stones or transforming into a limpet, The Stone Age is a call for us to experience our landscapes as intimately as those before and beside us; to live so very deeply and to really look around us, acknowledging our differences to learn from one another. Not only has Hadfield instilled in me a new way of seeing, but within this collection of poems she has truly owned her own experience, and that is the most impressive thing of all, her thoughts ‘a fog dark sea green lens glittering with a thousand facets’.

*

‘The Stone Age’, is out now and available here (£10.99). Read an extracted poem, ‘Gaelic’, here.

Blue Kirkhope is a writer, walker and birdwatcher from Glasgow who is currently based in Shetland working in nature conservation. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.