Charles Foster’s ‘The Screaming Sky’, published by Little Toller, is an awe-struck paean to the common swift; a numerous but profoundly un-common bird. Kirsteen McNish reviews.

It’s late April and I am sat in the smallest bedroom in the house, looking up at the eaves where we are lucky to be visited, for three months of the year, by Apus apus: the common swift, or ‘devil’s bird’, who are also known as ‘the screamers’, ‘swashbucklers’, ‘dark arrows’, ‘souls of the departed’, or ‘blades of the air’. I have heard so many descriptors, and yet so few that really capture the essence of these birds. I can see a pale mess of straw, grey wool-like matter, and half of a broken egg from last year’s brood quivering in the breeze, and I imagine it thrumming out a vibrational message, calling them.

We moved into this house seven years ago in July. As we pulled up carpets and painted walls, windows flung open and the sound of a music festival drifting over from the park on a summer breeze, we quickly learnt that we shared our house with these all-action paratroopers, who whizz past you so close you can feel the reverberations from their wings on your face, if you stand still on the doorstep for long enough.

Late last April, in a year that I needed news of their arrival more than any, my friend Luke texted me to say he had spotted a swift careering above the streets we both live on in East London. I felt jubilant, breathless, overjoyed and relieved. On the street my non-verbal daughter held my hand and looked up into my face quizzically as I buzzed like a pylon and felt something akin to, I imagine, an out-of-body experience — an unexplained lifting of the chest like when you watch virgin snow fall under streetlights, or a murmuration over fields at dusk, or feel the inexplicable first flushes of attraction, a natural high. And I know I am not the only one that feels a wave of emotion for these birds; an enduring love of swifts is not only well-documented by writers and poets like Helen Macdonald, Richard Mabey and Ted Hughes, but plain to see in my local community. A few years ago, a project centred around the swifts’ return took place in my borough, and people excitedly recorded how many they could see in the big skies above the marshes and chimney pots. Swift collages adorned many windows, precarious mobiles hanging at angles from curtain rails; emblems of love and hope for their arrival. Soon. Soon.

Charles Foster knows this feeling only too well. In The Screaming Sky he impresses on the page a reverence, an obsession, and eulogises about these tantalisingly high-riding creatures, as month by month he chases, follows, yearns for and details the behaviour of them with a chest-aching rawness and accuracy. His desire to watch swifts teem above him in the rip tide of the sky is a magnetic pull far greater than many around him can fathom. A man of extremes, he is self-mocking about the lengths he will go to to follow the birds; whether he’s losing his wallet after beach-sleeping to catch a glimpse of them in Mozambique skies, following their trail by train through Spain, or on tenterhooks as he drinks hibiscus tea by the Nile, he behaves like a man possessed with the emptiness of a partner who leaves without warning. It’s all about the waiting and an overwhelming urge to see them again; ‘When you talk about swifts you become an insufferable romantic by simply spelling out the facts’. At home in Oxford in May, Foster is giddy at his young son’s announcement that the swifts are back, his thoughts soon so preoccupied with the birds that his children think he is sulking.

We look back on a young Foster — a ‘Neolithic child’ who categorised, measured and constrained and whose hobby was taxidermy, corpses of animals badly stuffed, preserved, and sometimes strung up above his bed. As a youngster he gapes at the swifts in the skies above his house who seem to be made of tougher stuff than other birds — of ‘gunmetal’, ‘cut from a different cloth’ — and imagines them as flight commanders and killing machines. But the veil peels back and he starts to acknowledge his own mortality when he is handed a dead swift in a paper bag to stuff, and is shaken by the realisation that even the most resilient and impressive can perish. ‘I decided vulnerability was part of the web and the weave of the universe’ he writes. Back in the present day, this vulnerability vividly resurfaces as August’s fledglings peer and shuffle back and forth from the edge of their nesting place before they take the leap into the unknown; ‘a shift between states of being like the direct sublimation from a solid to a gas’. Based on their evident intelligence, Foster warns us not to presume, however different their experience may be to ours, that the swifts don’t suffer some kind of grievance when their offspring’s flight is unsuccessful.

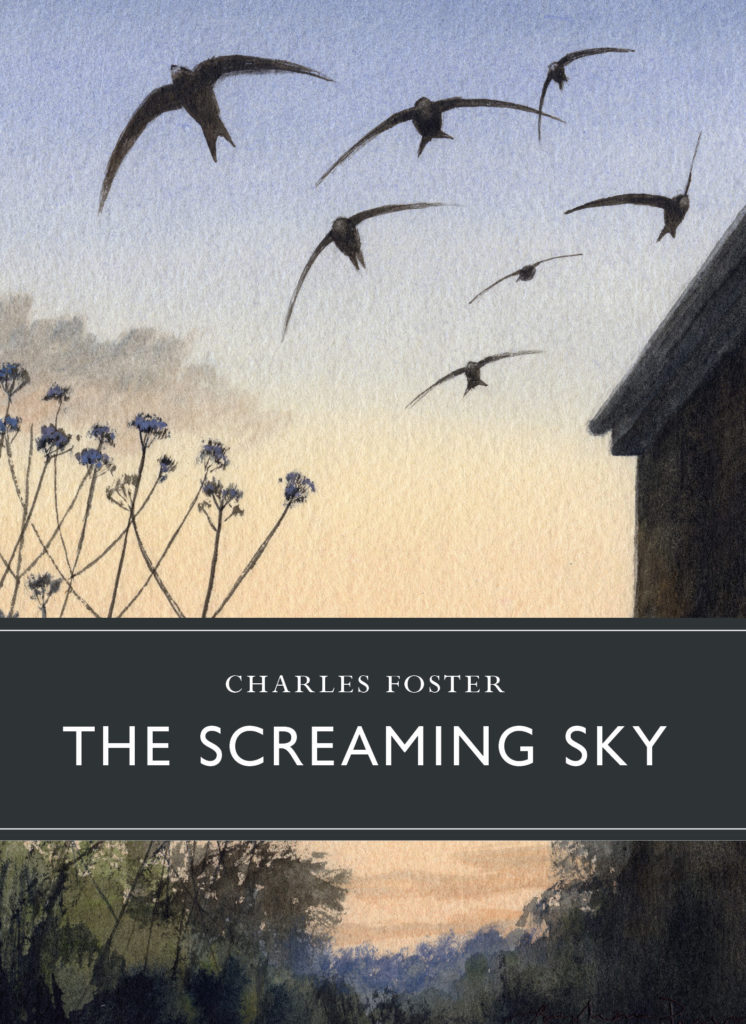

At first, I admit to feeling slightly intimidated by this book — the level of biological detail, the documentation, the figures. Foster is learned, academic, and can propel swift facts at the reader about as fast as the birds can loop and speed through the sky. He is unapologetically obsessed, yet doesn’t wish to possess their spirit or impose meaning upon them — he goes as far as to categorise admirers of swifts as kind of domesticators, slanderers or mystics. He debates a kind of ownership people adopt around swifts, in opposition to understanding and respectful, distanced appreciation. ‘Imprisoning wild things, even if it’s only in your mind, is a serious offence’ he warns. I winced as I fiddled with the swift necklace that hangs around my neck, realising my own relationship with these birds is emotional, spiritual and unscientific; all about the symbolism of the arrival, the hope and hurrah of the welcoming party. I have whiled away hours searching for paintings of swifts and swift jewellery to pin to my walls and to my coat, but not yet properly read Jonathan Lack’s classic book Swifts in a Tower that I was so thrilled to find on eBay. I have marvelled at the lengths of their journeys and felt breathless considering how many countries they cross travelling freely and joyously without passports or borders, anthropomorphising the formidable resilience and romance of flying thousands of miles across the — but I had not considered until I read this book how many are lost to storms, the dwindling resources of the tens of thousands of types of bugs they feed on, how modern architecture is taking away their bolt holes, or where they disappear to at night. Foster provides so much deeply memorable information — accounts of how Swifts partake in “banging” eaves, (a kind of prospecting for next year’s homes), their musty tobacco scent, how they fell suddenly from the skies in a cold snap in Kent in the 1800s and how the naturalist Gilbert White insisted that they hibernated under water; instances of swift bones found in ancient settlements and the beguiling account of a WWI pilot who happened upon a motionless group of swifts seemingly sleeping in a cloud — and to top it all off, there are beautiful illustrations by artist Jonathan Pomeroy (author also of On Crescent Wings, a personal account of his own relationship with swifts), whose work Foster knew to be the perfect partner to his paean to these winged creatures.

In the wintering months we find Foster in a sort of lament, looking for signs, holding onto news or sightings in a way that we all do when grieving after death or the end of a relationship. Here in the letting go, real poetry dwells. He’s found wanting and hanging out in the places the swifts used to frequent, making tentative enquiries, feeling pathetic, grubby and needy…and in one last stab at hope, he pursues their flight to Mozambique where he is sprayed by a halitotic whale, and watches the giraffes sway in the baobabs, and yet ‘still they do not come’. He boards a plane home, crumpled, hoping they will make one last salute, but they are gone, no lingering farewells to be had.

As I finish the book, my phone rings and I listen to my friend talking about the sting and colours of losing her partner almost a year ago as the blossoms reached their fullness. As she speaks, I look out the window and can’t quite believe I see a first swift of the year high over the yew tree. I am soon out into the street in my socks, looking up and pondering Foster’s kaleidoscopic, impressive, expansive book; how he really tries to inhabit the swifts’ world, choosing not assume or project but to look outward, to evolve. This is a book, most of all, about gratitude for things that cannot last. As I go back indoors, I am suddenly reminded of a sentence from A. S. Byatt’s Possession:

For my true thoughts have spent more time in your company than in anyone else’s, these last two or three months, and where my thoughts are, there am I, in truth.

*

‘The Screaming Sky’ is out now, published by Little Toller. Buy a copy here (£15.00).

‘On Crescent Wings: A Portrait of the Swift’, by artist Jonathan Pomroy, is published by Mascot Media books.