In his latest quintuple-whammy review, Ian Preece relishes fresh new sounds from Wau Wau Collectif, Snow Palms, KMRU, David John Morris and Fletcher Tucker.

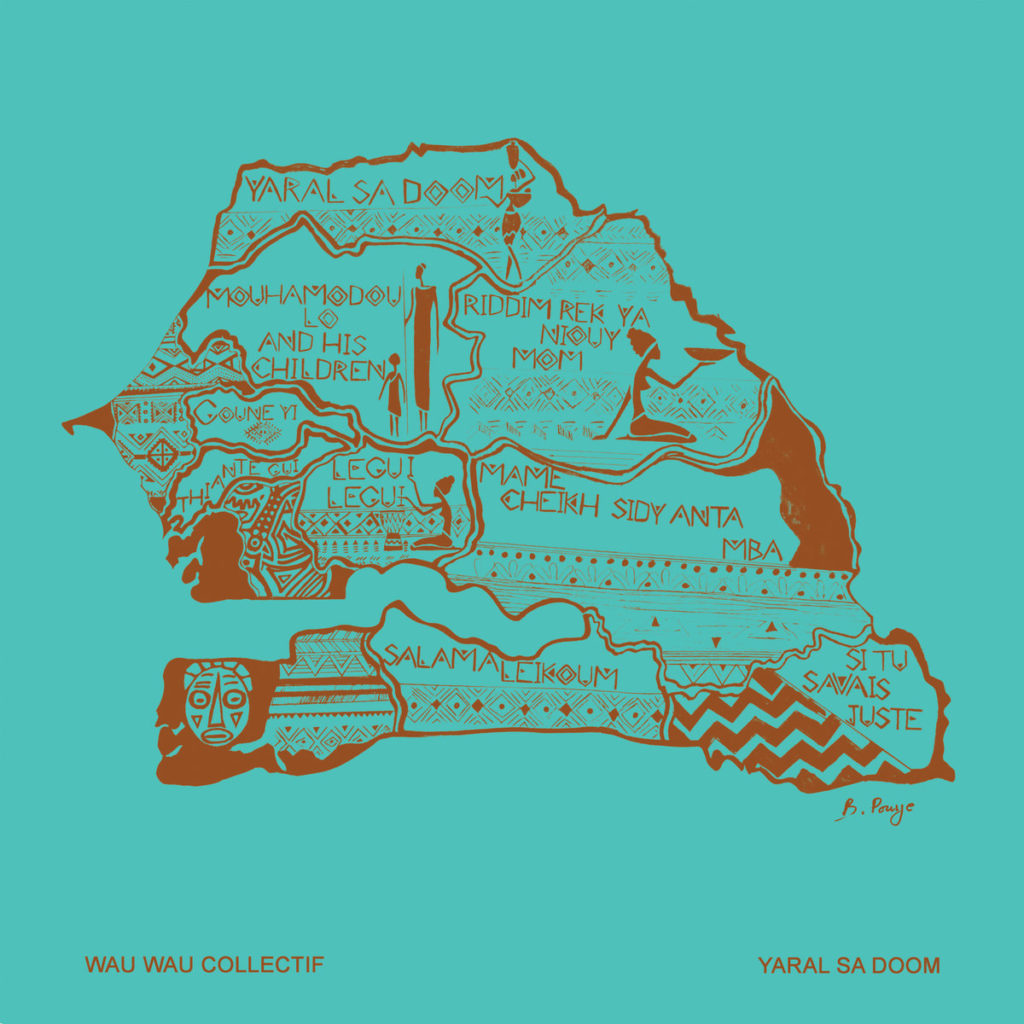

Wau Wau Collectif, Yaral Sa Doom (Sahel Sounds/Sing-a-Song Fighter)

Some albums you’re destined to never tire of. The opening title track on Wau Wau Collectif’s Yaral Sa Doom gently chugs along with a hazy, lo-fi dubbified back beat; the happily ringing Xalam (Hoddu/lute-style) guitar line of Jango Diabaté’s ‘Thiante’ follows – a beautifully simple, spacious melody that, in other hands in other African countries, could sound not a million miles from, say, the mbira of a vintage Hugh Tracey field recording, or some rural outback Kenyan guitarists like Jimmy Bongo or Johnstone Ouko Mukabi: upfull yet sad, beautifully melodious, life-affirming and melancholic all at the same time. It’s when the loping gait and close-mic’d, gravelly-voiced call and response of ‘Mouhamodou and His Children’ gives way to Maria Arnqvist’s smoky saxophone – then the gorgeous breathy ascent and twinkling percussion of ‘Salamaleikoum’ – that you realise this LP really is something special, and should sit as widely appreciated and acknowledged in the world as a kind of Senegalese Dummy, Club Classics Volume 1 or Blue Lines.

‘Yaral Sa Doom II’ opens side two and is revved up with some almost ecstatically groovy flute and organ (and beautiful sax again) which slowly builds and fills out around Arouna Kane’s rough-edged vocal. Djiby Li’s flute is back, floating around the rap of ‘Si Tu Savais Juste’ like Brian Jackson grooving with Gil Scott Heron, or a cool sample intercut with MC Solaar. There are ghostly echoes of Baaba Maal and Mansoor Seck’s Djam Leeli, as well as floating traces of haunting melodies like those from beautiful vignettes ‘Patrimone’ and ‘Yela’ off Lewlewal de Podor’s Yiilo Jaam, an earlier release from Senegal on Sahel Sounds.

The Wau Wau Collectif are a 20-strong group of Senegalese and Swedish musicians corralled and instigated by Karl Jonas Winqvist, and recorded by Arouna Kane at his studio in Toubab Dialaw, by all accounts a bohemian enclave south of Dakar, then finessed between Stockholm and West Africa. The beats crackle and the faint brushstrokes and washes of ambient, sax and flute lend a warm but slightly off-kilter hue that’s at once irresistible while also leading to some speculation in certain quarters online that this is another case of western appropriation, packaging and smoothing over of indigenous music for the bland but lucrative European World Music market – a take that’s fairly insulting to all the musicians involved and completely disregards the impeccable lineage of Sahel Sounds, the Portland label responsible for an exemplary kaleidoscope of African sounds, be they a Balani show block-party mash-up of sped-up hip-hop and balafon, gritty Nouakchott wedding songs, raw Hauka ritual trance music, gentle tende or Tuareg guitar. The big wheel keeps on turning – peacefully, loyally, as Arouna Kane has it in ‘Salamaleikoum’, summoning up a time when there were no visas, no frontiers and everyone was equal. As Mouhamodou is keen to share with his children: when the rains don’t come, and the cabbages don’t grow, the debt multiplies; life is hard when you’re working the land. You have to pass on wisdom to educate the young; you have to unite to fight the common cause. A truly beautiful piece of work (that’s being repressed on vinyl in the summer). Listen here

Snow Palms, Land Waves (Village Green)

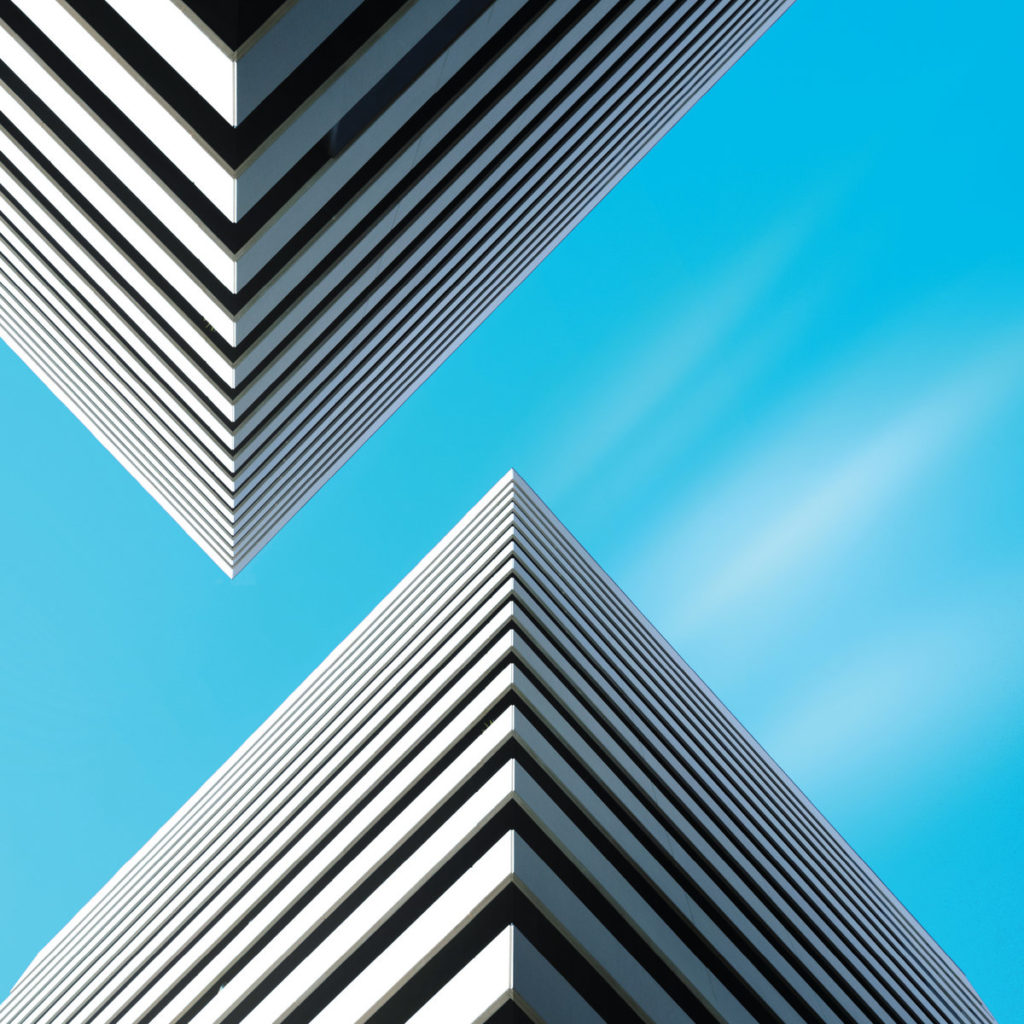

In The Wire recently Made Kuti was talking about Steve Reich: ‘I really like the process of minimalist music, using a small idea to create something very, very large and big. There’s repetition, development, but it’s not too much, it’s always very calm.’ Snow Palms’ Land Waves isn’t as austere as, say, Music for 18 Musicians, but that description still fits here too. There’s something gloriously frenetic and intense about much of Land Waves, but it’s never overdriven – there’s a beautiful measured poise and restraint; multi-instrumentalists David Sheppard and Matt Gooderson knowing just when to pull back. ‘Everything Ascending’ is a beautifully apt title: an insistent bass throb builds and builds into an epic synth workout of Kraftwerkian proportions – only for the pulse to flicker and drop back and the soundworld to fill with soprano sax squiggles; ‘Land Waves’ is similar, cresting magnificently, whipped up by brass and reeds before dropping away into Megan Gooderson’s stretched vocalisations. The mallets are out again for both the climax – there’s something about the polyrhythmic cushioning that reminds me of the well-upholstered sound of The National’s Sleep Well Beast – and for the fleet-footed ‘Kojo Yakei’, which translates as ‘factory night view’: a track inspired by the Japanese practice of taking nocturnal bus trips out of town to view the lights of petro-chemical plants and oil refineries beneath the night sky – a spectacular array of purples, greens and neon illuminating futuristic industrial architecture. Patterns shift, repeat and fold over each other; sax, flute, clarinet and bass clarinet weave in and out of the percussive grid; there’s ebb and flow before the crashing rhythms of life burst through the speakers in glorious Technicolor. This is a fantastically exhilarating trip for headz with access to the warm analogue glow of a decent hi-fi. It somehow manages to be as pristine as a Rachel’s chamber ensemble LP; as ecstatically precise as Glass or Reich; yet as pleasingly anchored to a rich, warm, fuzzy low end as Tortoise in their ‘Djed’ and TNTmoment. There are contemplative moments too; calm pools in the serene Japanese water garden. ‘Thought Shadow’ is gorgeous in an airy Kes-soundtrack-meets-Ryuichi-Sakamoto vein; by the time of the closing ‘White Cranes’, photographic stills, memories, images have all flashed by the windows of the bullet train as it gently pulls into the station. Listen here

KMRU, Logue (Injazero)

On my ceaseless trudges over Wanstead Flats in recent weeks (months) – past the inevitable solitary magpie, the newly brazen brown rats, beneath the big east London sky starting to fill again with jet planes – the music of Joseph Kamaru, aka KMRU, has been a fairly frequent companion. Kamaru wanders the highways of Nairobi and, more recently, the strasse of Berlin, tape recorder in hand. Field recordings were pureed to form the very texture of last year’s Peel – beautiful waves of ambient sound accreting particles in a ceaseless longshore drift; depositing rather than disintegrating loops. Of the 14 million comparisons to Stars of the Lid so far committed to print in the last quarter of a century, Peel is the closest in terms of tone, space and infinite galaxies of breathtaking expanse – if not in instruments used. Now comes Logue, a collection of older self-released digital-only Bandcamp tracks corralled together on clear vinyl for exemplary London/Istanbul label Injazero, which feels perhaps a more strident precursor to Jar, a recent tape of quietly glowing ambient electronica on the Frankfurt label Seil. In a nutshell Logue is more cinematic, the samples dance about and ricochet through the soundfield – there’s a terrific old-skool swooping descent on ‘Jinga Encounters’; a here-we-are-at-the-end Koyaanisqatsi(ish) feel is also present in the repeating patterns of ‘OT’ and the hazy portent and sequenced bleeps of ‘Argon’. ‘Und’ is beautiful: ripples of water, birdsong, dreamy piano and a luxurious sense of space all entangled in a mise en scène which brings to mind a slowed-down Max Richter’s ‘Dream 13’ from Sleep (or the work of label-mate Mike Lazarev). ‘11’ builds from there, hovering synth chords and a flickering breakbeat that never quite explodes into Omni Trio effervescence but is never less than invigorating. ‘Bai Fields’ and the title track shimmer with what sound like traditional kora lines, or something from Kakraba Lobi’s Xylophone Player from Ghana run through a 23rd century prism, all blooping liquid notes and crystalline, glistening fractals of (in the case of ‘Logue’) repeating patterns of Glass-like sound. ‘Points’ unfurls slowly with poise and elegance, glitch and crackle that situates the LP alongside recent high watermarks on LA’s Leaving Records like Green-House’s Six Songs for Invisible Gardens or the desolate yet beautiful wash of static that is Ana Roxanne’s ‘It’s a Rainy Day on the Cosmic Shore’. If you didn’t know you’d never guess Logue was a compendium – it hangs together beautifully as a whole. Not quite complete but essential early works from a versatile musician with a fine ear. Kamaru recently told Pitchfork how, when DJing, he wants people to hear how he’s ‘feeling with sound’ – but everyone always wants to dance. ‘Dancing’s good. But with field recordings you’re listening to the surroundings. There’s so much to learn and understand from our surroundings with these sounds. You need to listen.’ Listen here

David John Morris, Monastic Love Songs (Hinterground)

Not to trivialise anything, but I’d say David John Morris of Cornish-folk-troubadours-exiled-in-London, Red River Dialect, made the right decision when he retreated to the Gampo Abbey monastery in Nova Scotia in 2018 – at the very least he’d have been future-proofed for the pandemic, one step ahead of everyone else in getting their priorities right. But also, during his time taking ordination as a Buddhist monk, he emerged from a cabin overlooking the blustery Gulf of St Lawrence with a new set of songs and then, once disrobed, headed over the water to the famed Hotel2Tango studio HQ of Montreal’s Constellation records where the likes of Fly Pan Am, Exhaust, Esmerine, Frankie Sparo, A Silver Mount Zion and, of course, Godspeed You Black Emperor! all put down the raw, ascetic sides of legend back in the late 90s/turn of the millennium, the sound of which so impressed a young David Morris back in his teenage bedroom in Cornwall. Useful press release nuggets aside (none of the above was planned before the retreat), I’m now totally convinced some of that lean, impassioned, Spartan rigour – that communion wine in the pipes of Hotel2Tango – has carried itself into Monastic Love Songs, Morris’s new solo record (and that was before I realised Thierry Amar, of the various Godspeed/Constellation collectives mentioned, showed up to play double bass). The sound could also be down to Thor Harris, a drummer from Texas, ex of Shearwater now in Swans, who drums like an American – that’s to say with lots of rumbling space, suppleness and subtlety – no skin-bashing or unduly heavy pummelling to within an inch of the kit’s life. What I really love about Monastic Love Songs are the gently unfolding and trundling, stripped back and slowly building melodies – especially on tracks like ‘New Safe’, ‘Earth & Air’, and the gorgeous ‘Circus Wagon’ and ‘Steadfast’ – and the warm bass and drum thrum. So, while I can surmise the presence of particles of crisp Montreal morning air trapped in, say, A Silver Mt Zion’s He Has Left Us Alone But Shafts of Light Sometimes Grace the Corner of Our Rooms, there’s definitely an undertow of bands like The Strugglers or Mojave 3 – rustic, modest, beautifully low key, and not screaming ‘look at me’. There’s ruminations on life in the monastery here, the need to step free of the ties that bind before the boundless ocean; and also, perhaps, the view from the back of the tour van, the need to escape the music industry circus. Whether it’s lyrics pertaining to sharing earphones listening to REM, or a poem of thanks to a Tai Chi practitioner at the abbey – a rush of oceanic gratitude embracing the chaos and inspiration of life; an immense wave washing away the ‘sandcastles of aggression’, cleaning the slate and enabling ‘baby turtles fresh from the shell to go on to discover their turtleness in empty black depths’ – the cosmic and the beautiful are discernible in the everyday. I once, unsuspectingly, caught Red River Dialect playing with Southern pickers House and Land and Dylan Golden Aycock in amongst the dusty rubble and exposed wiring of the Old Dentist’s in Hackney – god, it’d be great to just wander into that kind of happening again. I was reading some sleevenotes about the healing music of South African pianist/saxophonist Bheki Mseleku recently, and his journey through exile. There’s a similar (if less overtly political) inward–outward, retreat-versus-grappling-with-the-world voyage here, reflected equally beautifully in the music – resulting in, I think, a happy spiritual cleansing. Listen here

Fletcher Tucker, Unlit Trail (Adagio830/Gnome Life)

Even more off-grid was Fletcher Tucker’s last LP Cold Spring, a tone poem/homage/offering to the wild grasslands, mountain streams and coastal fogs of Big Sur, where’s he’s eked out a living growing vegetables with school kids at the Esalen centre, writing poetry, reading Gary Snyder and Joanna Macy, making music and releasing records on beach-glass coloured vinyl on Gnome Life, the label he runs – home to present day West Coast beatniks like The Range of Light Wilderness, Little Wings and Jeremy Harris, and troubadours of yore like Robbie Basho. Cold Spring synthesised multiple layered field recordings from the locale, blending buzzing frogs and crickets with ululating coyotes. Like a J.A. Baker of the Santa Lucia Mountains lying in wait in the sagebrush with a tape recorder, Fletcher told me (when I interviewed him for my book on independent record labels) that at times he felt like packing it all in because there was little point in attempting to replicate the impossible – there being no human-made sound more beautiful than listening to the wind as it hit Big Sur off the Pacific Ocean. Dark and gloomy in places, but solemnly beautiful in others, Dark Spring is Fletcher’sGesamtkunstwerk of music and place. Unlit Trail, a kind of compact, portable Dark Spring (in some instances reworking fragments of the same songs for live performance) follows in its wake – shorter but no less stunning in its minimal poise and richness, and recorded in an isolated cabin on the shores of a lake not far from the Norwegian border while Tucker was in Europe on tour with pedal-steel maestro Chuck Johnson. When the needle rumbles over the deep crackle of a lakeside fire at dusk on the opening ‘Summoning’ it’s as if Thomas Köner has relocated to northern Sweden – few sounds are so deeply pleasing, maybe even more so than the Pacific breeze; and the bassy crepitation returns both at the end of the track and the record, surfacing from beneath waves of lugubrious melodeon and leaf rattle. In between, scraping bells fade into beautifully plaintive, reedy flute (‘Visitation’), and Fletcher’s singing/spoken-word animist incantations sit atop the pump organ and mountain dulcimer like Nico intoning over her harmonium. A totally captivating, immersive trip. Dim the lights and ne’er cast a clout till May is out. Listening instructions are best quoted from Fletcher’s sleevenotes: ‘I welcome the swaying trees outside your window, the sleeping mice in the attic, the subterranean river surging deep below the city street, as well as your ancestors and mine, to gather close and listen in.’ Listen here

*

Ian Preece’s ‘Listening to the Wind: Encounters with 21st Century Independent Record Labels’ is published by Omnibus, available here.