Tim Dee takes in the soft and olden punkery of new Subway Sect album ‘Moments Like These’.

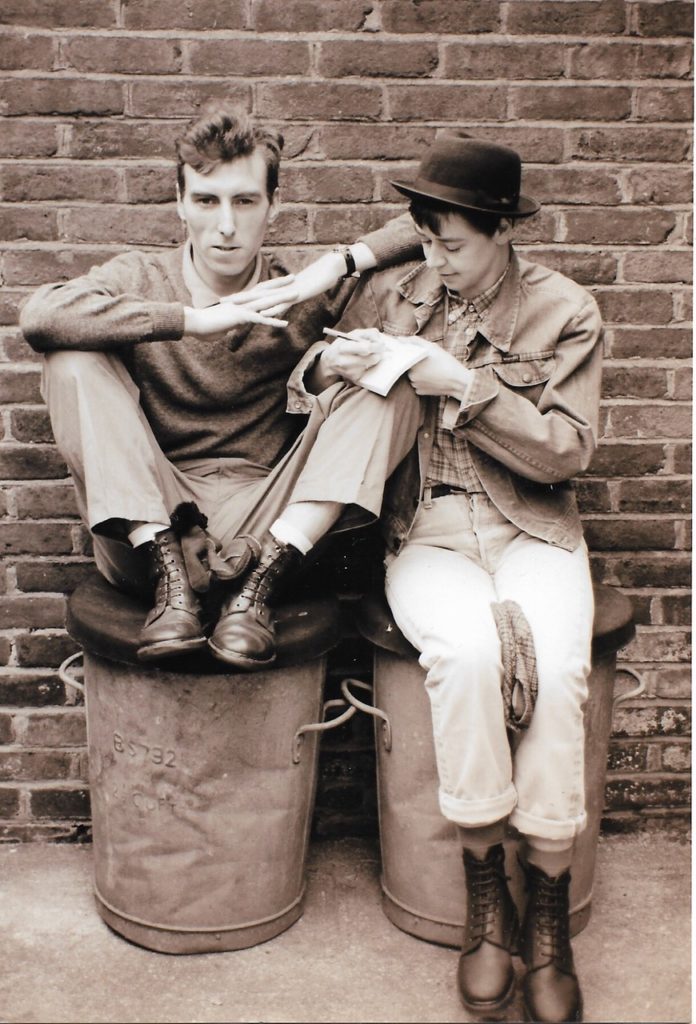

Vic & George, Kew, 1993. Photo by Alan Horne.

Most of the Blank Generation didn’t die before they got old; a number (constantly surprising) of those are still musically active who, forty-plus years ago, signed up to an attitude that pitted (as a central tenet) youth against anything older (music, politics, sex, art, emotions, the whole shebang). Bob Dylan at eighty and making it all new is a wonderful thing, but it isn’t as surprising to me as Vic Godard releasing a record in 2021. Surely punk was never meant to be pensionable.

Rimbaud stopped writing poetry when he was twenty-one. Shouldn’t the punks have shut up too? Can a zeitgeist time-travel? Might those in their old age still be New Wave? It seems especially contra for a music with such an explicitly youth-oriented stance. Punk was about teenage kicks (for and against) and awakenings into a first, near-adult, engagement with the world and the self, which usually meant a not-impressed account of that world and that self. There were not many songs about afternoon naps. A few years ago, Dan Nichols, a relative of mine and just a little younger than me, had a fun skiffle group and a song called ‘Punks Not Dad’ which made my point but with more laughs.

*

Some kept up with Subway Sect through the years. Vic Godard had a jazz decade: a rather loungy piano sound with dangly and mostly harmless lyrics. He didn’t punk his ride but nor did the raffish polish of his new material stick, for me at least. Listening to the tinkling and smoothery makes you think amateurishness is much more his profession. He wasn’t Noel Coward or The Style Council; he wasn’t Tom Waits. Chas and Dave were nearer neighbours. Perhaps he wouldn’t have minded that. Maybe that is where Punk Vic went in his middle years. We’re against all rock ‘n’ roll, he had said, but maybe a jazzy meander down Soft Irony Lane will impart the same message. He certainly wasn’t touring to reprise the early song ‘Nobody’s Scared’ that starts: ‘Everyone is a prostitute singing a song in prison…’ One Subway Sect hiatus was followed by others. Vic Godard became a postman.

Now, though, there is mail for all: this new record and a (sort of) new Subway Sect. Excellent amateurishness is back, and it suits the sixty-plus Vic Godard. The wholly excellent professionally amateur writer and critic and publisher Sukhdev Sandhu, who started out in Gloucester, then conquered London, before chasing down New York City, has got it together to release Moments Like These as part of his Texte und Töne series which is otherwise mostly book-type publications. The vinyl album is produced by Mick Jones (late of The Clash) and features the 1981 Subway Sect line-up, Vic Godard with Sean McClusky, Chris Bostock, Johnny Britton and D.C. Collard. There is a wonderful booklet too with photographs and essays (some of the best writing on punk I’ve seen) by Steven Daly, Kevin Pearce, and Stephen McRobbie. It is out now.

The record is good and sounds to me like a homecoming for all of punk. I’ll mention just one song, the last: ‘Time Shoulda Made A Man O’ Me’. All the album is inward-facing, almost apologetic; it is chamber music of a kind, and it won’t be everyone’s favourite by any means, but I found it very lovable. Its punkery is soft and olden and very knowing; if late-style punk exists, this is it. There is nothing on it as musically militant as Subway Sect were once, it has better produced and more powerful guitars but is sweeter edged; the music can be funny, the songs are self-mocking, the air in it is all healthily decompressed, it has energy still but is far from uptight, it is not tragic. The whole feels at home with itself. Its reach seems modest but genuine. It doesn’t do the big stuff that, say, Nick Cave is tackling these days or Joe Strummer did with his ‘Ramshackle Day Parade’. There is very little audible ego. Vic Godard was always an old guy in his music even when he was a young one, and here his age and his sound come across as one and the same. Throughout, there’s a beautifully modulated sense of him and his songs getting ready to be gone. In that, I guess, it is most likely to appeal to others of the same age and ilk.

The last number is perfect. It is a self-deprecating singalong that reminded me of the bitter-sweet farewell songs of some of Shakespeare’s clowns. It cheers you up and down at the same time. It does asides and has a voice over. It talks to its audience as it might in a pub session. Vile evils are obviously still vile evils, as the early single ‘Ambition’ put it, and we are all surely prostitutes, but what can you do? We’d have liked to see a few more of you here of course, but we hope to be back next year, so keep your ears open…it is all just a matter of time. This song says what Moments Like These as a whole has done, I think, which is to have punked punk.

*

I don’t look promising as an informed veteran of 1976. Your reviewer is a sixty-year-old man wearing, today, a powder-blue cotton-knit sweater and grey fleece tracksuit bottoms, both bought for their loose comfort from some adverts at the back of a Sunday newspaper supplement. I have hearing aids in my ears and reading glasses perched on my nose. There is no record player in my present home, no vinyl albums or singles, no CD player or CDs. I listen to the occasional music I listen to almost entirely off my laptop and through headphones when my wife has gone to bed. It is very rarely anything that I think of as punk. And yet, the more I decry my qualifications, the more I find myself thinking of Vic Godard.

Because I was born in 1961 and was therefore a teenager, and switched on by music, in the second half of the 1970s, I couldn’t not be a punk. The coincidence of me and the years is my only real qualification. Sure, for a year then or more, I wore flared cords and frizzed my long hair (by plating it when wet) for Saturday discos in the Scout Hut in Henbury in Bristol, but I already disliked all uniforms and was, in any case, simultaneously, teenagerly, osmotically absorbing the quite un-corduroy rough magic of those revolutionary musical months. To hear punk was enough to make me one – to come to it and pay attention to it was something I found I wanted to do; it noisily seemed to demand it, if only for a couple of minutes at a time. You, you discovered in listening to it, were talking to, and learning about, yourself through others’ music and words. At the same time, for me, various bits of poetry began to somehow stick to me. I barely understood more than a line or so of these, but I started to inhabit some of the poems they came from, feeling certain that they pertained. They spoke to me, and they spoke for me too. I carried them about my person as I carried some songs. And what started as interesting quickly became essential. I needed the poems and the music to live. Some punk (or New Wave music, I’m using punk here to mean almost every new music made out of the autumn of 1976 and on through the late 1970s) had the urgency of a dream: the secret personal seriousness found within that comes to the waking surface, the truth of which you might keep with you forever: an emotion, mood, gesture, a cast of mind. In this way, punk was literally formative for me. I am not a living fossil like Iggy Pop, but it turns out I am still the punk I found I was when I heard ‘Ambition’ for the first time in 1978. I’ve double checked by listening again. I’m the same, even in my elasticated trackies, I am that man that was that boy.

*

Extracted from a much longer essay exclusively available to Middler and Lunker-tier Caught by the River subscribers. Supporters can access the full piece in all its 4000-word glory by either logging into their Steady account, or checking their email inbox.

Not yet signed up? You can take out a subscription here.