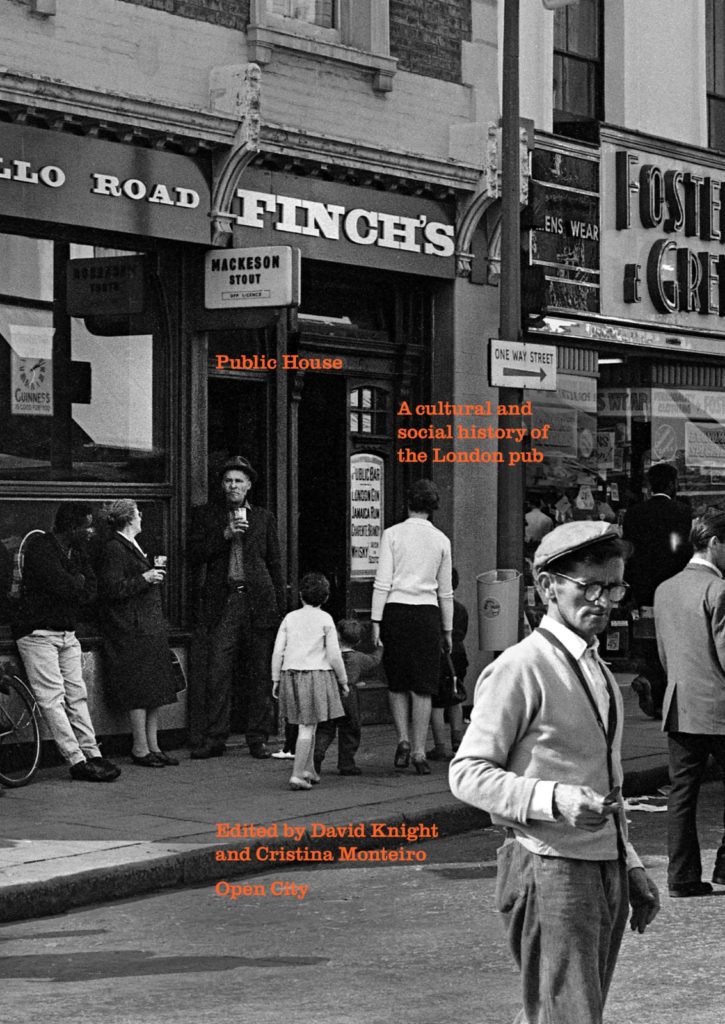

‘Public House: A cultural and social history of the London pub’, edited by David Knight and Cristina Monteiro and published by Open City to coincide with this year’s Open House Festival, tells the story of London through its pubs. John Grindrod takes a sip.

Patrick Hamilton’s Hangover Square. Muriel Spark’s The Ballad of Peckham Rye. Samuel Selvon’s The Lonely Londoners. You can find many memorable London pubs in works of literature, but there are few books dedicated to the city’s public houses themselves. But, just as we needed it most, here is one to down like John Mills with a pilsner in Ice Cold in Alex, a splendid reminder of the joy of the London boozer.

Public House: A cultural and social history of the London pub, edited by architects David Knight and Cristina Monteiro, operates chronologically, opening with Southwark’s The George Inn dating from 1388 — the year Chaucer’s pilgrims set off for Canterbury from the Inn next door — and ends up in 2021 with The Carlton Tavern, which was demolished by property developers in 2015 two days before it was due to be listed, and has since been rebuilt after a brilliant local campaign. In between there are loads of my favourite pubs recorded in short entries, photography and the occasional essay. There’s the Fitzroy Tavern, home of Doctor Who fandom and, also where I watched Kelly Holmes win the 1500 metres gold medal at the 2004 Athens Olympics while I was waiting at the bar, an event which has ever since undermined my blanket aversion to sport on TV in pubs. The Vauxhall Tavern, where I spent most of the Saturday nights of my adult life dancing at Duckie. The Royal Standard in Croydon, whose beer garden sits in the shadow of the town’s flyover. One of the things that most struck me was how many of these pubs I have actually visited over the years. It is by no means a complete list of London boozers, indeed a number of my favourites are absent, but it is a representative sample of the different sort of urban and suburban watering holes you’ll find throughout the city. For me the joy of this book is that it brought memories of nights out I had long forgotten, while also making me thirsty to explore pubs I had never heard of.

Throwing ‘pennies’ at the ceiling at the Fitzroy. Picture Kitchen / Alamy Stock Photo

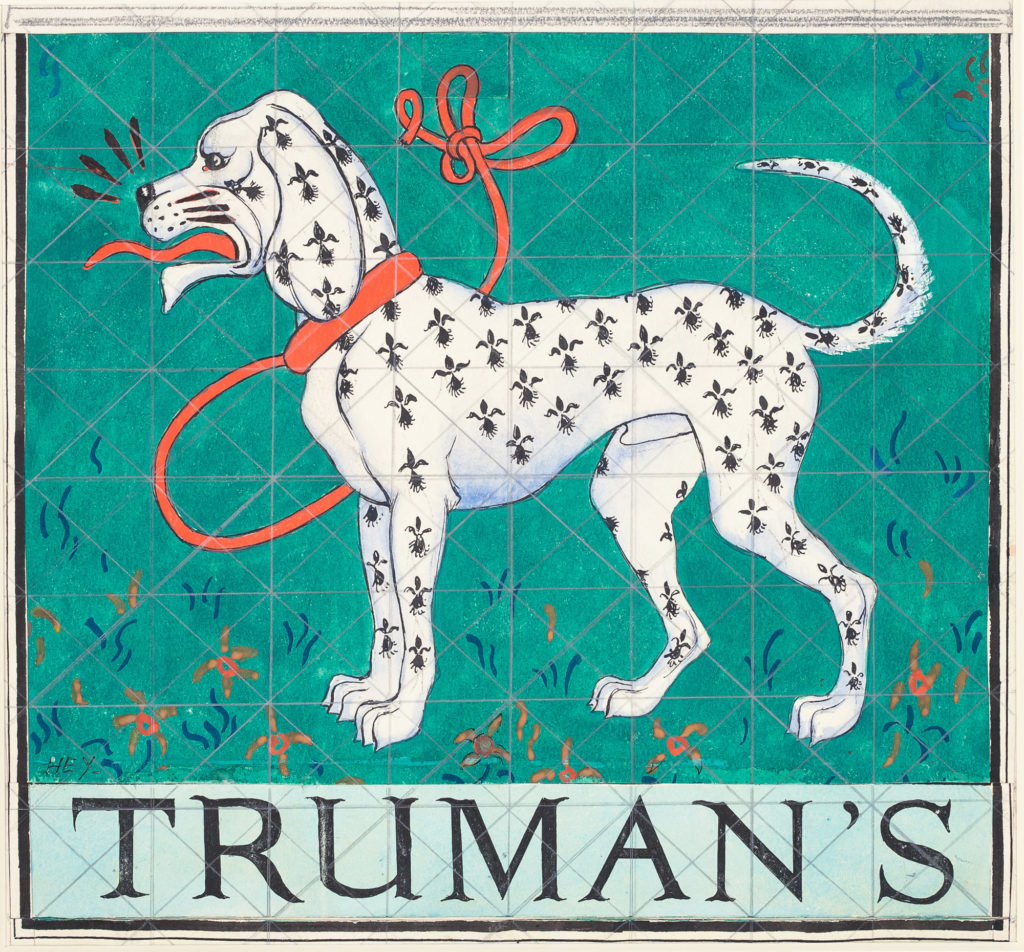

Public House has echoes of Geoffrey Fletcher’s 1962 book The London Nobody Knows, famously turned into a psychedelic documentary film in 1969. Partly it’s the ambling scope of it, the diverting asides, the delight at the curious and arcane. But it’s also the palette of the illustrations, a poppy array of orange and green that gives it a trippy feel of late Beatles and swirling pub carpets. And what illustrations! There is beautiful documentary photography: a band in full swing at Brixton’s Coach and Horses, the first pub in London to have a black licensee – Oliver ‘George’ Berry – in 1965; embossed glass being cut in 1900 for a pub window; revellers at Horse Meat Disco in Vauxhall’s The Eagle, all capturing a sense of energy and excitement. But there are glorious still lives too: the elaborate Victoriana of Camberwell’s Union Tavern in 1897; the swish 1961 modernism of Marylebone’s Wargrave Arms; the familiar set of the Queen Vic from EastEnders. Alongside that we have line illustrations and tons of ephemera, from flyers and tickets to pump designs and pub signs. There are contributions from Sadiq Khan, Isy Suttie, Luke Turner and Bob Stanley among others. Stanley’s work feels particularly at home here as the tone is reminiscent of St Etienne’s London Trilogy of documentary films, musical elegies for lost places and fleeting moments.

Illustration c1950 of beer engine handles

David Knight’s introduction is particularly helpful and evocative. Here he takes us through the evolution of the London pub, from alehouse to coaching inn, tavern to coffee house, and beyond to the extravagant ring-road sprawl of 1930s roadhouses (now mostly vanished) and modern micropubs. Stretching back to the early medieval period alehouses began as domestic spaces modified to serve beer. Coaching Inns were a by-product of roadways and pilgrimage routes, convenient stopping off points for the weary traveller. Taverns were designed to serve imported wine, while coffee houses became regular scenes of political debate. As an architect as well as a writer Knight delights in the evolution of the pub’s design and function, and his enthusiasm infuses the whole book.

This handsome hardback, illustrated on almost every page, is the product of Open City, the organisation who among other things run London Open House, allowing us access to some of the city’s most extraordinary private dwellings. So why are they publishing a book on houses that are, by their very nature, public? Well, perhaps it’s all down to timing. In the normal run of things this might feel an anomaly, but we are well past living in Normal Times and so this celebration of the boozer arrives just as we are beginning to wonder if life can or will ever return to how it was, or what form it might take in the future. As a symbol of the social and community life we have missed, the pub is a wonderful emblem. Celebrating what had been the casual everyday now feels like a civic duty, even if many of us are hesitant to embrace it.

Cicely Hey, ink and watercolour designs for inn signs, c.1936. Courtesy Abbott and Holder

The pub as an institution has been hard hit by the smoking ban and lockdowns. But that doesn’t mean the good times are over. This book shows how they have adapted over the centuries, diversifying from simple boozers into homes of everything from political discussion, live music and stand-up to real ale deification, microbreweries and gastronomy. Even as a non-drinker I have really missed the casual joy of the pub, as a home from home, neutral ground on which to meet the world, a place to while away hours in company or alone, to people watch and eye the décor, to laugh, cry and on occasion, behave very badly indeed. While the book makes me nostalgic for those long afternoons and evenings gone by, there is a hopefulness to it, a sense that here are some of the most adaptable and beautiful spaces we have created, and that beyond our current struggles we will still need them and seek them out, hang about and joke with the bar staff, to feel a part of something. Like The London Nobody Knows this would make a wonderful film too, full of echoes and afterlives and unexpected encounters. But then going to the cinema is another matter — perhaps a worthy of a follow-up volume.

*

‘Public House’ is out now and available here, priced £18.99.

John Grindrod is the author of ‘Concretopia’ and ‘Outskirts: Living life on the edge of the green belt’. You can follow him on Twitter here.