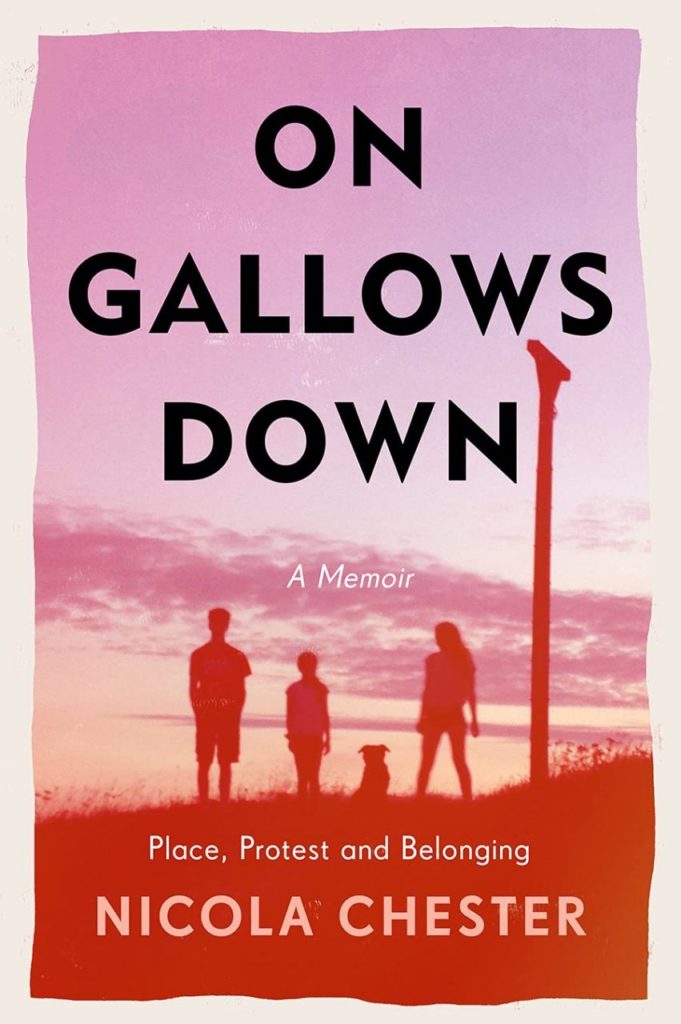

Nicola Chester’s ‘On Gallows Down: Place, Protest and Belonging’, published by Chelsea Green next week, is our first of two Books of the Month for October. The following extract is reprinted with kind permission from the publisher.

Rural Work

The Dew Pond on the Height

Some stories are reabsorbed into the landscape and gone like the lost ‘white horse’ of neighbouring Ham Hill, the thin green turf growing back over the chalk scars of a curved neck and withers, the angle of hock and fetlock. Those members of the Bloomsbury Set, hiding out in this small, remote downland village, might still have known it. They trekked up the steep, orchidy slope to picnic there, scandalising (possibly) the locals with their naked expression, bisexuality and the complicated geometry of their relationships. (The locals may have just been grateful for the work, the opportunity for entertainment and a validation from the ‘upper classes’.) But stories do and have left their mark on the narrative history of the landscape; a stain upon it, like the strip lynchets of an old farming system that resurfaced in hot, dry spells or old, wall-sized maps discovered hidden in the cellar at the Big House on the Combe Estate, marked with great patches of common land, pre-enclosure, or on brand new maps, bought to replace ones worn soft as cloth, which revealed new open-access land, glowing at the edges of previously well-kept, fenced-off secrets.

Snowdrops and yew trees concealed the footprint of an old cottage and a flint-lined well, and bomb craters, indistinguishable from dry dew ponds, or Bronze Age ‘pond’ barrows shelter deer, hares and flocks of golden plover. There were the burn scars left by stolen, torched cars and gouge marks in the ramparts where the gamekeeper’s Land Rover was pushed off the hill after a monumental rave.

Below the hill in summer, thin green lines run across the stubble, like green crayon on yellow paper, where the corn has been continually trampled by the night traffic of badgers and the tougher grass has grown through. Even when the field is ploughed, the trail reappears, trotted out like a watermark returning; an ancestral, indelible line. You could track it for a mile as it runs up and over the rounded hill, where it turns pale; a seam stitched over the hill’s breast, a silver stretchmark, a badger’s desire path. The white chalk horse has never reappeared, though.

The feeling of being a small part of this great landscape’s story, and the constant highs and lows of its conservation rollercoaster, kept me engaged and on a taut, singing wire. The juxtaposition of gain and loss, the lurch from despair and frustration to exhilaration and delight, led me to believe that if I just kept going, kept trying, I could change things, despite repeated setbacks. I was hooked. I couldn’t let go. My love for this landscape has rewarded and hurt in equal measure. I was all in.

We managed to hang on to some of the scrub and gorse on the hillfort and limit the sheep grazing. A compromise was struck that suited all parties. The following year the birds returned: snipe, woodcock, golden plover, short-eared owl, barn owl and even the ruff and a small number of grey partridge. But the more I looked into things, the more I could see that here, and on almost all other farms around, an inexorable mass extinction of agricultural wildlife – wildlife that had evolved to live alongside us and that had been celebrated throughout our culture and literature – was well underway. An ecological holocaust was taking place. The contract farmer alone, with his knapsack weedkiller or the sprayer, with mower or hedgecutter, was totally indiscriminate, mowing at the most sensitive times, cutting hedges after dark, when birds had gone to roost, or spraying on windy days – a one-man environmental disaster area. The estate manager, who had had his eye on things and who had introduced widespread conservation measures, was posted abroad. Suddenly, everything was sacred, nothing was safe.

In everything I did, I tried to spread the word. I took writing and wildlife workshops into schools (and out of them) and the ’keeper and I did talks and guided walks, attempting to show how a farming and shooting estate could support wildlife too. We did a series of talks for some influential American ladies who were guests at the Big House. It was a hopeful attempt, and one I believed in. There was plenty of push and pull during our talks, plenty of banter, open disagreement and good-humoured challenge. I thought, ultimately, it was working.

Yet all the while there hovered the precariousness of a tenanted life. The tentative influence I had on the country estate relied on toeing the line, on being non-confrontational, on the largely feminine wiles of thoughtful gentleness and suggestion, patience, flattery and positivity. Sometimes it galled. I could not deny that this was, first and foremost, a farming and shooting estate, and I had to acknowledge that. I could choose to walk through it and the community I was part of, railing against wildlife-denuding practices, or I could engage with it, get people onside and persuade them to find a better way to allow, include and encourage more wildlife. I even went beating – the part of a day’s shoot where a team of ‘beaters’ walks, pushes and eventually flushes pheasants in from whole hillsides away, so that they fly over a line of guns and are shot at. I had a complicated and difficult relationship with it. On the one hand, the day involved walking through the heart of challenging and beautiful terrain in all weathers with my dog, spotting wildlife and sharing the thrill with a rural, working and knowledgeable community, while on the other hand, there were the nonsensical ethics of shooting on an increasingly commercial scale – for ‘sport’.

I could convince myself that it was done well here; each ‘gun’ was given a brace or more of oven-ready birds from the previous shoot, while the rest were sent to restaurants or the game dealer. It helped knowing that the extensive acreage of wild bird cover and nectar strips, the new copses and hedges planted, the beetle banks and field margins were all in place because of the shoot. That the purchase of additional tons of wild birdseed, the seed hopper and the gamekeeper’s time to feed the songbirds from October to March was funded by the shoot; that scrapes were dug in the woods or on the edge of fields to provide a habitat for waders (not to be shot). That I would never shoot anything. That the pheasants were caught up and bred from here each spring; that ravens, kites and buzzards nested unmolested in trees inside some of the release pens and were welcomed – by then, the poults were mostly too big to be taken, and if some were, what of it? The fact that the presence of goshawks and sparrowhawks was celebrated. The fact that those animals traditionally considered ‘vermin’, such as polecats, stoats and weasels, magpies and jays, and even those foxes that weren’t an immediate ‘problem’, were not only tolerated, but their presence accepted and enjoyed. Apart from the pheasants and partridge bred on the estate, no other ‘game birds’ were shot.

And the money came in handy. It paid for Christmas. It meant there was a little teapot stuffed with notes to fall back on and our winter weekly shop was stretched out with many a pheasant casserole. Often, it was the only meat we had.

It was work. I found wry comfort in discovering that John Clare, the agricultural labouring poet, worked with the enclosure gangs – the very enclosures he lamented. Enclosure brought an opportunity of employment Clare could not turn down: fencing, hedging, the destruction of trees or lime-burning – all to enclose the former freedoms of his own parish. It also brought fresh faces and new opportunities to socialise. Clare scholar Professor Simon Kövesi wrote in his book John Clare: Nature, Criticism, History: ‘There was no economic space for Clare to consider not doing the paid work of enclosing his village, or of lime-burning; choice is a product of socio-economic power, and he had none. There was no front for resistance because poverty denied space for that activity’.

We were not living in poverty. We hovered just above the line where benefits kicked in. But things were undeniably tight and stressful at regular intervals. There was no give, no buffer. Like John Clare, we didn’t really own anything. We had bookshelves of books, some clothes, photographs and bits of furniture; minimal crockery, four pans, three wine glasses and enough cutlery for seven. The curtains, carpets and oven weren’t even ours. My parents lent us money to buy a car and bought us winter tanks of heating oil and mattresses for the children’s beds; my parents-in-law bought the children’s school shoes. Neither my husband nor I had life insurance or passports. Even the horses we rode and looked after every day were borrowed and I worked part-time in a library – whose whole ethos was borrowing. I cleaned for one of the big houses, owned by an extremely wealthy family who used the house for occasional weekends and breaks. I was required to keep it top-end hotel standard and all worked well for a while, but the pay was erratic and I could never quite shake off a feeling that I was being watched. Written notes on how to do things a particular way (and not the way I had been doing them) were particularly unsettling, as were the times when the chauffeur-butler suddenly materialised when the family were away, at one of their other homes. On one occasion, when I hadn’t been paid for three months, I picked up over £300 worth of notes strewn over the bedroom carpet. Another time, I collected up loose pages from an event the family were organising that appeared to contain the mobile numbers of celebrities and the nannies of royal children. I carefully stacked the cash and the pages on the bedside cabinet and waited another few weeks for my money. A lot of good food got thrown away (until I made the decision to take it home) and I’d wash, iron and hang up beautiful clothes that my employer’s children would have grown out of the next time they visited.

My home was not mine. With a change of someone else’s heart or plan, or a rent hike, we could effectively be homeless with three children and a dog; a whole community built up and belonged to – gone in a couple of months’ notice. There was nothing else we could afford to rent locally. It sometimes felt like a precarious existence, and had been so since I left home, almost 30 years before.

Kövesi mentions Clare’s enjoyment of the company he kept with the enclosure gangs; the socialising and the drinking. However, along with the effect of bone-tiring work, he lamented the distraction from his writing. We enjoyed the camaraderie of the beaters’ company too: it was very separate from the paying guns – we barely came into contact with them and rarely spoke. If our paths did cross, there might be a nod, a ‘good morning’ or an occasional thank you. It was routine to be ignored. But I enjoyed the feeling of belonging to a motley crew of raggedly dressed, deeply rural people of all ages; the (sometimes tongue-in-cheek) country lore and connections to the land that went back generations. I loved the comfort of the pub afterwards, or the fire; wet dogs and coats steaming, discussing, mostly, the wildlife we’d seen. But I grew increasingly uncomfortable with it; the bits that didn’t add up. In particular, the unacknowledged, unregulated and increasing scale of it as an ‘industry’ and its unquantified impact on native flora and fauna. At dusk, when the pheasants were clumsily going to roost in the trees, the cacophony of cock birds coughing out their alarms triggered all the others in the vicinity, from estate to estate, into Hampshire, Wiltshire and on. The sound echoing and reverberating off the hills and rolling round the combes was an overwhelming wall, drowning out all other sound, louder than the big tank guns that thundered away on Salisbury Plain – and set the birds off again.

*

‘On Gallows Down’ is published this Thursday. Pre-order your copy here via our brand new shop.

Read a recent interview with Nick Hayes conducted by Nicola Chester here.