As Patrick Wright’s ‘The Village That Died For England’ is reissued by Repeater Books, Luke Turner considers how the English rural intersects with nationalistic and militaristic ideals.

The sun burned the mist off Salisbury Plain as I drove south towards the Dorset Coast via the white chalk horses and ancient monuments of Wiltshire. The A338 meanders through fields of barley impatient for a combine’s chew and past thatched barns, golden stone cottages, Salisbury cathedral spiking the emerging blue of a perfect Indian summer, a timeless picture postcard England. Yet this is also a martial terrain. On Salisbury Plain, you’re as likely to see an Apache helicopter gunship hovering over the fields as you are a kestrel, and there are as many red-rimmed triangles warning of tanks crossing as there are brown heritage signs pointing you to nearby Stonehenge. As well as these practical militaristic interventions into the view from the Honda window are the symbolic and monumental: war memorial monoliths, a pub called The Churchill Arms, bronze sculptures of archers and next to a rugby club a full-size Spitfire fighter is lofted above the road.

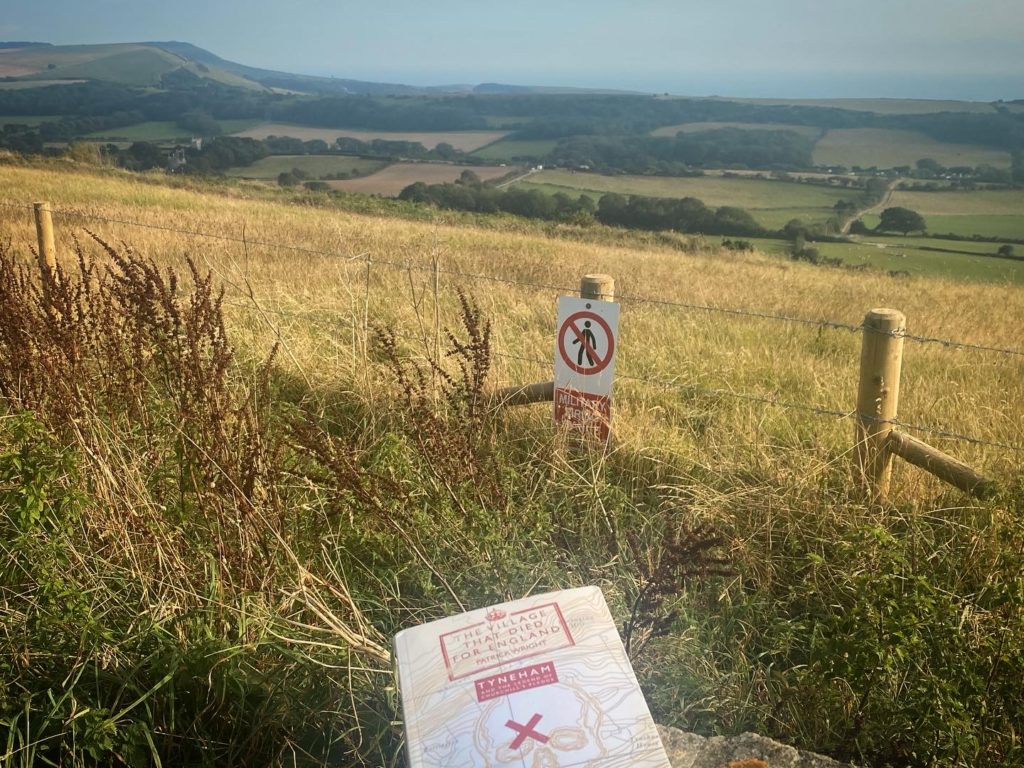

Thoughts of how the idealised English rural often intersects with the nationalistic and militaristic power of place were on my mind that day as I headed to Tankfest, a sort of Glastonbury for fans of armoured warfare. This takes place at Bovington Camp, a military base just north of the coastal Purbeck valley that is the focus of the book that sat on my car’s passenger seat – Patrick Wright’s The Village That Died For England, first published in 1995 and now reissued by Repeater Books.

Wright’s book is a deep investigation of the story of Tyneham, the small Dorset settlement that was evacuated in 1943 so that British and American troops could use the surrounding downs, woodland and heaths for training with live ammunition in the run-up to D-Day. The villagers and residents of nearby farms and manors were promised that they would be able to return to their homes once the war was over, yet despite their sacrifice the army held onto the land in the national interest, and they never did.

I first read The Village That Died For England in the early 2000s as I thought about how the specificity of the English countryside made me feel beyond the merely aesthetic appreciation of the curvature of a hill or infinitely complex manifestations of the shape of a tree. The Dorset countryside is what Wright had in mind when he coined the term ‘Deep England’ in 1985 book On Living In An Old Country, a survey of the power of nostalgia during the years of Thatcher’s rule. ‘Deep England’ is a landscape like the one that connects the Vale of Pewsey, where I’d begun my drive, with the Tyneham valley. It is a subjective, slippery place of nostalgic symbols, idealised topographies, hearty evocation constantly under threat by pernicious outsiders and the roar of modernity. If Deep England has a sacred text, it is This England, a magazine that recurs in Wright’s work, and one I remember from childhood years loving its sentimental pictures of rolling hills, traditional farming methods, timber-framed dwellings shedding golden light onto crunching snow, not realising that the text that accompanied the rural porn was often steeped in anti-immigrant, anti-modern, reactionary rhetoric. Patrick Wright’s intensely researched books are nevertheless energetically unacademic in tone, a rattling blend of history, mythology, politics and sociology. The Village That Died For England blew my mind, for just as Derek Jarman’s Modern Nature helped me understand a queer radicalism in some of our underregarded English places, so Wright’s text is a red triangle sign warning that there are always layers, some troubling, to our motivations for preserving supposed idylls, traditions, and lost utopias.

My original copy from Faber’s 2002 reprint had the subtitle ‘The Strange Story of Tyneham’, now replaced in this new edition by ‘Tyneham And The Legend of Churchill’s Pledge’. I wonder if the amendment, along with the new cover of a skull in the Dorset downland contours, has been done to attract browsing eyes in the ongoing culture wars that insist that Winston Churchill was either a irredeemable racist or unimpeachable national hero, rather than the reality that he, like all history, contains a multitude of truths and contradictions. In any case, anyone from either blinkered side of that pointless argument lured in by the subtitle would be disappointed by Patrick Wright’s nuanced writing.

Wright never sentimalises the Purbeck valley. What evocative passages of purple prose there are can be found only in the exertions of those who fought over Tyneham in magazines, leaflets, radio broadcasts, newspapers and speeches in the decades after the Second World War. Wright’s clarity makes his own insights all the sharper in a powerful reconnaissance that reveals much about the way any landscape takes its meaning from the eyes of the beholder, and not necessarily from those who live within it. There are no ‘heroes’ in the arguments over Tyneham, for whom the village exists as a pawn, increasingly battered by the weather and stray gunfire. Some battled for the return of those few who once lived there, the creation of a National Trust reserve, or the necessity of maintaining the gunnery range as vital for the continuing defence of the realm against the foe of the day, be that Nazi, Communist, or imagined. Some sought a return to an idealised rural idyll of class hierarchy, tradition and quaint cottages that were of course never the damp, lice-infested hovels of truth. Conservative politician and historian Sir Arthur Bryant was one of these, an early campaigner who led from the perspective of a ruralist who saw Tyneham as a symbol of an England that might be used to resist the modernisation of the post-war Labour government. Later groups made up an unlikely coalition not just of traditionalists but also ‘animal welfare campaigners, former labourers, ecologists, anti-hunt activists, footpath militants, suspected rural fascists, and at least one UFO-spotting admirer of the “Great Beast” Aleister Crowley’. Many of these welcomed the presence of the army as a defence against unsightly bungalows and crowds of mass tourism. Some ecologists saw the army as a well-equipped security force protecting rare habitats – a memorable passage in the book features an army officer detonating spare plastic explosive in order to create ponds for newts. These different groups, some intersecting, at times in bitter conflict, populate the imaginative territory beyond the flora, fauna, steel and cordite as Wright’s lens widens to encompass Mike Leigh’s superlative 1976 TV film Nuts In May, Dennis Potter, D. H. Lawrence, the Kibbo Kift, Enoch Powell, Shakespeare, the Scouts, countryside and beyond.

This is Patrick Wright’s second book to be published this year, following new work The Sea View Has Me Again, ostensibly about German writer Uwe Johnson’s time on the Kent island of Sheerness. I’ve never read a word of Johnson’s novels, but that doesn’t detract from how in that book Wright weaves together the decline of shipbuilding, small town poverty, sea level rise and municipal drainage and the bomb-laden wreck of the SS Richard Montgomery to shine a light on our present moment. Indeed, though written thirty years apart, The Sea View… and The Village That Died… are wonderful companion pieces, two of the best books I can think of about the state of Brexit England, and just how we got here.

Tankfest was a bewildering cacophony of roaring diesel engines, squealing tracks, the sharp report of blank ammunition, the chatter of excitable lads queuing for a go at the gaming stations set up by sponsor World Of Tanks, or for photographs with a Tiger (the mean Nazi war machine, not the creature that came to tea). Live commentary of mock battles and the hits of Now That’s What I Call Music WWII blared tinnily out of PA systems and I spent a while in the blazing sun talking to a bloke dressed as a member of the Wehrmacht, trying to understand what motivated him to do so. Knackered by the intensity of it all, I drove out of the carpark and followed the satnav up the slope of the northern side of the Tyneham valley. The road leads along the ridge, with red flags limp in the calm evening air marking the boundaries of the firing area. At the viewpoint (during the summer the venue for a street food pop-up), fresh-faced lovers readied their camera gear for sunset pictures for a #vanlife instagram account; another couple many decades older debated as to whether they’d have the energy to walk to a bench on the edge of the car park. You can’t drive any further, as a metal gate blocks the lane that is still signposted ‘Tyneham’, alongside boards warning of your likelihood of getting hit by an errant shell. I looked over this valley, squished between the edge of the chalk and the sea and for the last 80 years pelted with tonnes of high explosives from our national arsenal, and watched it sink into the quiet blue of the summer’s dusk.

*

‘The Village that Died for England: Tyneham and the Legend of Churchill’s Pledge’, published in a new edition by Repeater Books, is out now and available here.

Patrick Wright and David Edgerton discuss the book at a free event, ‘Blasted England: how we got from D-Day to Brexit’, in London this Wednesday. More info and tickets here.