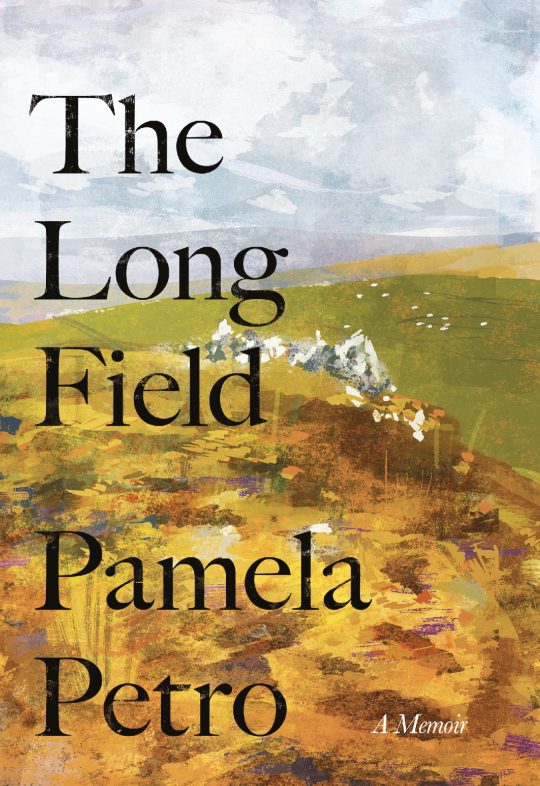

In an extract from her book ‘The Long Field’, recently published by Little Toller, Pamela Petro contemplates the ‘perpetual letter dance’ of learning Welsh.

In Wales, most houses have names rather than numbers. Moel-y-Llyn means ‘Bare Hill by the Lake’. Penbryn means ‘Hilltop’. Glasgoed is Welsh for ‘Green Woods’. Glan-y-mor is ‘By the Sea.’

Through their names, houses sing their patch of countryside. They sing often of the sea and occasionally of the woods. Their constant refrain in this corrugated land tells of hills high and low, sunny and shaded, blue, green, silver, of hills covered in crows. (I like this last one a lot. It’s called Bryn-y-Brain.) Harlech is the name of a great castle, but you find it on private homes, too. It means ‘Beautiful Rock’. There are many, many rocks in Wales.

These days I often stay with good friends at Tŷ Pwll, which means ‘Pond House’. They have a perfectly round pond in their back garden, watched over by a stone dragon. (Don’t fear the ‘w’ in Pwll – it looks like a dark secret, but it’s just a Welsh vowel. Pronounce the name as TEE-poolh.) Toward the end of my Master’s course I lived at Dolwerdd, which means ‘Green Meadow.’ Dolwerdd was a bungalow built by a farming family for extra income. It was here I encountered the tumult of unmatched wallpaper. Outside, gently rippling sheep and cow pastures of the Teifi River valley hemmed it all around. Every now and then the sheep would find a way through the fence, and I’d wake up to a woolly army in the garden. On those mornings, eyes still closed, I’d assume I’d accidentally left the radio on overnight. The ewes’ guttural baaaaas sounded just like the chants of disapproval I heard in the background of Parliamentary broadcasts.

I lived at Dolwerdd again in the early 1990s when I took the Wlpan course for Welsh learners, taught on Lampeter’s college campus each summer. ‘Wlpan’ is actually borrowed from the Hebrew word ‘Ulpan,’ which means ‘studio’. It’s the name of an intensive language-learning programme devised after the founding of Israel to teach immigrants Hebrew – fast. Think linguistic boot camp and you won’t be far off.

Class all day every day including Sundays for two full months. Trample cognition, wear it away; expose the reptilian part of the brain that only repeats and accepts. No questions asked. That was the goal.

The first day we were split into groups. Because of construction on campus my group met in a Portakabin – a trailer kitted out to look like a classroom – in the middle of the hockey pitch, where, stripped of every form of protection, it could be slapped and shaken by terrific gusts of rain.

Our handouts that day came with a Surgeon General-style warning like the kind found on cigarettes: ‘Intensive teaching can be physically and mentally exacting. Applicants should be sure of their ability to cope with the stress involved.’

In the cabin, teachers threw beanbags or balls at us when we conjugated verbs. It was supposed to hone concentration. We were pummelled with genders and conjugating prepositions (really – prepositions, too?), and something truly awful called the Mutation System. One teacher dubbed this the Mutilation System. It causes the first letters in certain words to shapeshift, so that Cs become Gs, Ps become Bs, and so on. Remember Glasgoed, the Welsh house meaning Green Woods? The word for ‘woods’ is coed, but here it has mutated on contact with the adjective glas, meaning ‘green’, to become goed.

Personally, I don’t need this to happen in a language. The perpetual letter dance makes using the dictionary tricky at best, a kind of sadistic game at worst. And there are not one but three different kinds of mutation. You can spend all afternoon looking up ‘goed’ and it will get you nowhere. Believe me, I know.

In the second week of the Wlpan a car backed into my path as I rode my bike from Dolwerdd to campus, and I somersaulted gracelessly over its hood, thudding to a stop on a halfway-paved road strewn with tiny pebbles. Shortly afterward, a critical care doctor picked scores from my skin with tweezers while teaching me a Welsh word that I’ve never forgotten. Pwythau. ‘Stitches.’

I was late for class that day, but eventually arrived at the Portakabin hobbling on a cane. A game called Trichneb – ‘Disaster’ – was in progress. The vocabulary drill went like this: John had an accident on the way to Lampeter. He lost his: leg, arm, head, teeth, etc. Everyone assumed I was part of the exercise.

That was the day we learned that we weren’t merely ‘taking’ Welsh, as I once ‘took’ French. We had become a new class of humans altogether. We were Welsh Learners. Nouns. People who had made a choice others might liken to a crime against practicality – ‘But what will you do with Welsh?’ – yet which really amounted to a political stance in support of a tiny nation and its minority language. Our teacher abandoned her principled use of Welsh and made this speech in English. Probably, I think, so I would fully comprehend that the sacrifice of my body had been worthwhile.

On the Wlpan we also learned that there is no verb ‘to have’ in Welsh, in the sense of ‘to possess’. Things, people, accidents, headaches, houses, even, are only ‘with you,’ as if by their consent. Mae tŷ gyda fi literally means, ‘There is a house with me.’ Only in translation does it become, ‘I have a house.’

‘Translation,’ said the other great Thomas of twentieth-century Welsh poetry – R. S. Thomas, born a year before Dylan, died nearly 50 years after – ‘is like kissing through a handkerchief.’ Action is conveyed, undercurrents of inference lost. A space is born between original intention and its representation in another language. There are kisses and then there are kisses.

When there is a house with you the subtleties of tone change. The house retains agency. It is entitled to a name. It is also a thing that may be taken away from you, or left, or destroyed, or handed down. While there is a vacuum of the eternal surrounding the sentence, ‘I have a house,’ a house that is ‘with you’ is engaged in a relationship, and relationships exist in time. Eventually you will leave it or it will leave you. Peer into the grammar of Welsh, and you begin to suspect it is steeped in ancient knowledge of the human heart.

*

‘The Long Field’ is out now and available here (£20.00).