An excellent new work of experimental literature by Daniel Williams converses with Fernando Pessoa, Georges Perec and Geoff Dyer, writes Alistair Fitchett.

Kevin Pearce, whose writing has always been and continues to be a source of great inspiration, once had a terrific habit of starting off a piece with the question “so what have you been listening to/reading recently?” Like the typical linguistic magpies that we are, I admit to having utilised the same opener on many occasions. Let’s revisit it one more time.

So what have I been reading? Well, the mention of Kevin Pearce is a neat way to introduce The Edge Of The Object by Daniel Williams, for both he and Pearce were co-conspirators with myself in the Tangents website and the Fire Raisers fanzine projects way back in the murky mists of time. The Edge Of The Object has its roots in history at least as ancient, since the bulk of the text was written in the blinking of an eye between those two projects, when Williams took himself off to a dilapidated and remote cottage in northern France to write. He’s more recently alluded to this episode in a tremendous piece for Caught by the River on the 30th anniversary of the release of Talk Talk’s Laughing Stock LP.

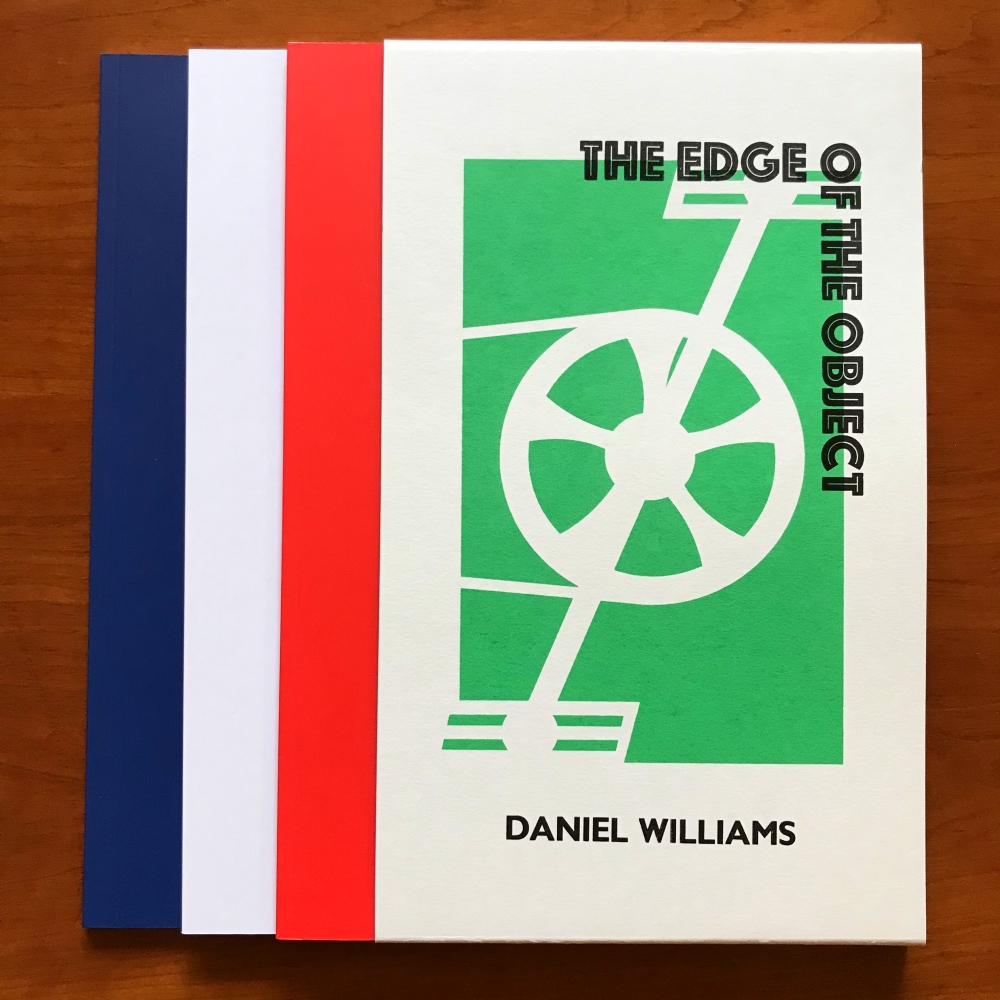

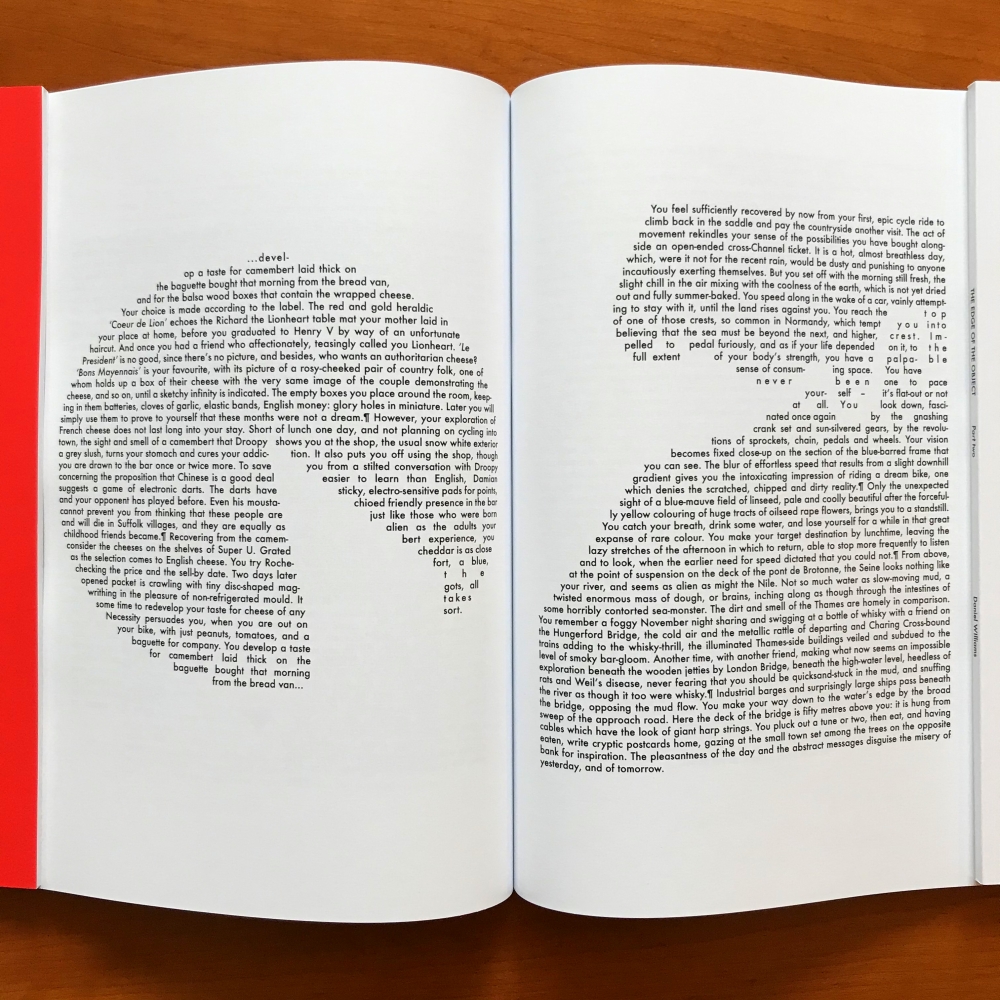

As one might expect given the title, it is the object that drives much of the book. If it has taken a quarter of a century for it to be published then in part this has been down to the challenges of Williams’ original concept of having the individual ‘episodes’ that make up part one and three as calligrams with text wrapping around, or within, the two-dimensional representation of objects suggested by, or implicit in the body of the text itself. That this conceit never feels forced nor detracts from the connectivity of the individual elements within their gently meandering narrative is both to Williams’ credit as writer and also to the skills of Tim Hopkins of The Half Pint Press for realising the ideas in physical form.

Hopkins may be familiar from his work on an extraordinary edition of Fernando Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet. Typeset and printed by hand using a tabletop letterpress onto a rich variety of objects, including 1960s slide transparencies, pencils, matchbooks and a myriad of other surfaces, the edition of 80 boxes deservedly won the 2017 MCBA International Artist’s Book Award. That project also highlighted Hopkins’ interest in literature that challenges traditional notions of narrative structure, and with Williams being drawn to similar threads (he has previously written a series of lipograms, one of which was published by Half Pint Press in 2017), it feels like a natural punctuation point on a journey of thirty plus years of friendship that the two should come together so perfectly.

If The Edge Of The Object hints at an interest in the experiments in literature by the likes of Pessoa and Perec, there are echoes too of Geoff Dyer in Williams’ prose. Of Paris, Trance perhaps most explicitly given the settings and the undertow of narrative, but more expansively in that sense of moment, of recording, of observation, of perception. The notion of the camera’s eye being that of the Other. The surrealist detachment and the anarchist’s detournement of the object. Perhaps too like The Book Of Disquiet, the individual ‘episodes’ of parts one and three of The Edge Of The Object can be dipped into and enjoyed on their merits as stand-alone pieces. Each are rich in their excavation of language, evocative of place, moment, person, hope, regret, whatever. They could be photographs piled loose in a drawer, plucked at random and enjoyed for their unique qualities. Being human however, the impulse to connect and create story from distinct elements is strong, and Williams adeptly weaves these notional photographs into a tapestry that balances self-reflective and personal memory with broader strokes of recognisable, translatable themes and experiences. The author both connects to and distances himself from the central narrative character by adopting the second-person perspective throughout these two parts of the book. It’s a striking technique that lends a detached coolness to language that is often earthy and luxuriously poetic, seeking out moments of remembrance like a tongue reaching to a loose tooth, prodding the peculiar ache of memory.

Perhaps then it is inevitable that my favourite of all these shape pieces is one which traces the map of the mainland UK and that documents Williams’ hitchhiking travels from town to town. I see the ghost of my young self in there, living in the town jutting into the sea like a nose and recalling how we ‘managed to clear the dance floor simply by taking to it, wild and unrestrained, misshapen, round pegs trying to fit into a square hole.’ I read this now and wonder if Williams, like me, almost fails to recognise the person who drifts spectrally from the text? Time is a strange creature, after all, warping and bending us into peculiar reflections of ourselves, like simulacrums stuck in a fairground.

I wonder too what the lightly fictionalised figures who inhabit part two of the book might make of it all now. This part discards the notion of shapes and reverts instead to a more traditional narrative, following as it does a collection of musicians from what we might have called the ‘indie-pop’ scene on a tour around France. The narrative voice switching from second to first person also helps secure the differentiation of the three parts of the book. Again, reading this in 2021 has a peculiar resonance of a fictionalised history being fragmented against the concrete barriers of time. Memory dwindles and fades into archaeological traces. ‘Reality’ is, as ever, dislocated and re-joined in altered states. Of course, to what extent that might be apparent to anyone less connected to the ‘reality’ is impossible to say, just as it is to consider how it might have been read had it been published in 1996 rather than 2021. What was it were saying about time being a strange creature?

Straddling the line between book as object, of literature as idea, and the perhaps more traditional landscape of narrative comfort, The Edge Of The Object manages to balance these elements into an absorbing and thoroughly enjoyable work. That it looks as well as it reads is testament to thirty odd years of experimentation, crafty tinkering and the hands-on experience of type design. It’s certainly been worth the wait.

*

‘The Edge Of The Object’ by Daniel Williams is published in an edition on one hundred copies by The Half Pint Press. Full details of the book, including info about a launch event on Dec 1st 2021 can be found here.

Daniel Williams can be found on his blog and on social media.