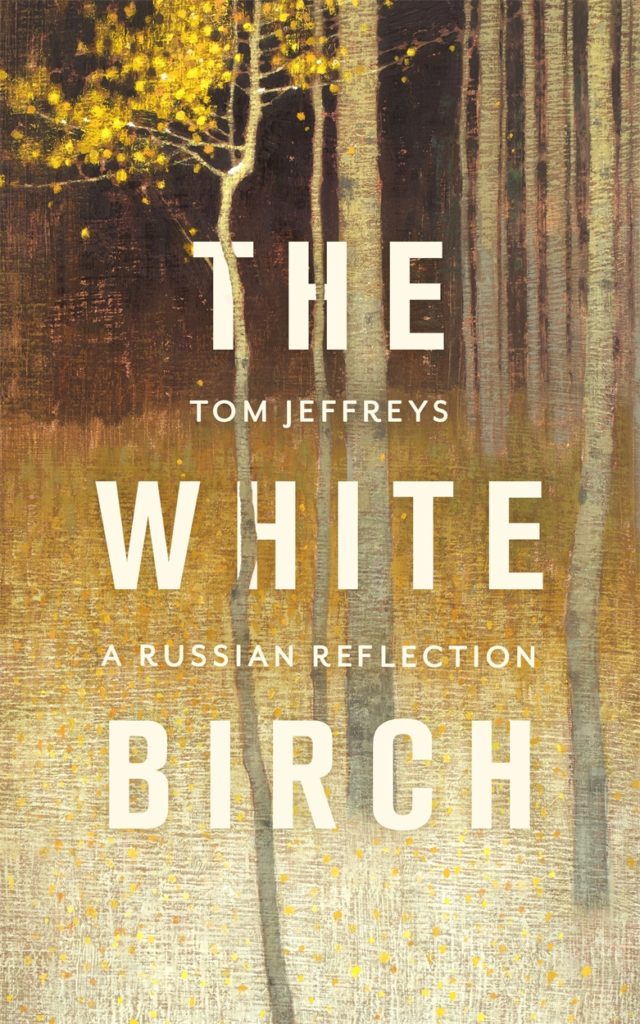

In continuing celebration of National Tree Week, an extract from Tom Jeffreys‘ ‘The White Birch: A Russian Reflection’, published by Corsair.

‘Landscapes with birch trees placed into kitschy, heavy gold-plated frames only attract a few tourists and the provincial nouveau riche.’

Ekaterina Drobinina, ‘The Russian Online Art Market’, Arterritory.com, 2015

The domes of Saint Sophia Cathedral glint gold and silver against cloudless turquoise skies. The foreground is a strip of white, the earth concealed, rendered clean and pure by a covering of pristine snow. ‘Once upon a time . . . ’ the painting seems to say. It points backwards to a dream-like past that remains miraculously unchanged today. Unlike many cathedrals in the UK, which so often seem like multilayered collages of their own histories, patchworks of different architectural approaches, this particular style of Russian church architecture appears to have fallen, faultless, from the skies.

Saint Sophia Cathedral in Novgorod was built in the eleventh century, but in this little painting it is difficult to get any sense of the building’s long history. It tells us nothing about the people who built it under orders from Prince Vladimir, the people who cared for it over the subsequent centuries, the people who looted it or defiled it – from Ivan the Terrible’s oprichnina (a kind of sixteenth-century state of exception) to the Nazis in World War II – or the people who subsequently restored it. White in a white landscape, the cathedral masks the traces of its history. It looks as if it landed yesterday or as if it has simply always been there. Even its name refers not to an individual saint who might be associated with a particular era or location, but, like Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, to sophia – the wisdom of God. Once upon a time this style, directing the eye upwards, was new. Saint Sophia asks us to look not towards other men but towards God and, perhaps in time, towards a Russia that transcends time. It has been here forever, it has only just arrived.

Dividing the composition is a single birch. It stretches the height of the painting, its leaves clipped by the frame at the top, its roots cropped at the bottom. If visible brushmarks are understood as evidence of the hand of the artist – and therefore of the time of the making and the individuality of the maker – then here the artist has taken their lead from the subject matter. The painting is flat and smooth, the paint carefully blended using small, soft brushes. Some might call it timeless; others bland. But not all of it: the handling of the birch trunk is quite different. It juts up and out from the pristine polish of the rest of the painting – a pile-up of impasto and bursting crusts of black and white paint. Unlike Sophia, this is a living thing, a tree trunk whose very form is a product of its living history.

And there’s more: this is not a painting on canvas or paper but on birch bark. The little horizontal lines known as lenticels that are so characteristic of birch bark are just visible through the white of the snow and the sky. The scene’s apparent purity is not quite as absolute as it first appears. A thought begins to emerge from the etymology of this dulcet word ‘lenticel’, which comes, via the French lenticelle, from the Latin lens: a lentil bean. It was only much later, during the medieval period, that it came to be associated with lenses and vision. It is an etymology not of signification but of formal similarity: both lenses and lenticels are, roughly, bean-shaped.

If I were in art criticism mode, I would draw this thought out a little further. I would perhaps make the point that the etymology of ‘lens’ is an appropriately visual one for this aid to human vision. I might mention that in some cultures the birch is known as the ‘watchful tree’ on account of these eye-like lenticels. I would try to find out whether the artist wears glasses.

If I were in art criticism mode, I would also note that the work is pointing to its own materiality, that in painting birch on birch in such a self-consciously painterly way the artist is explicitly nodding towards the diverse ways in which birch trees have appeared in Russian art history. In so doing, the work reframes an entire history of Russian landscape art and draws our attention to the complex relationship between materiality and representation, between signifier and signified. I would observe perhaps how the work points to the constructed nature of our relationship with nature, indeed of the very concept of nature. A depiction of birch on birch: the cracked bark here coming to function not only as itself but also as a depiction of itself. Birch presents itself bodily at the same time that it represents itself as type (species, symbol); birch as subject and object, surface and substrate . . .

And then I would cut it all down to fit in a 500-word magazine review.

Alas, I am not in an art gallery. I’m at one of the many souvenir stalls in Novgorod (or Veliky Novgorod, as it’s also known), a few hours’ train ride south of Saint Petersburg. These kinds of paintings are towards the more expensive end of the souvenir spectrum but that does not make them art – does it? There are dozens of them on display across the various stalls, many almost indistinguishable from one another. I consider trying to ask one of the stall-holders for some more information. But my Russian isn’t good enough and, besides, I’m not entirely sure I trust these ‘gallerists’. I’ve already made one purchase and been ever so mildly fleeced. I spotted a knee-high pair of woollen socks woven with pictures of swans and decided to buy them for my wife, Crystal. I ask the price; 450 roubles, the woman tells me, gesticulating with her hands. ‘Da,’ I nod in agreement. She takes the socks and disappears around the side of her stall for several moments. She then re-emerges, pointing to a sticker that was definitely not on the socks before; 550 roubles, it reads. A 22 per cent price increase. She shrugs, as if some unknown authority far away had made a decision and there’s really nothing she can do about it if that’s what the sticker says. I laugh: I know your game, lady. I split the difference, pay her 500, and we both part happy.

*

‘The White Birch: A Russian Reflection’ is out now and available here (£15.79).