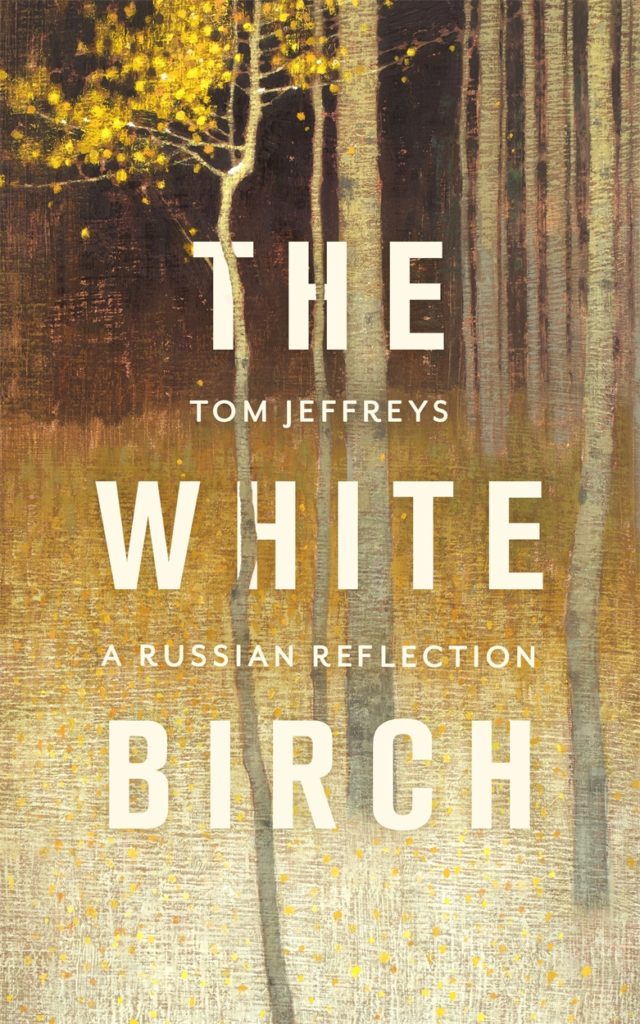

From Peter the Great to Pussy Riot: Mark Hooper reviews Tom Jeffreys’ exploration into Russia’s unofficial arboreal emblem.

Tom Jeffreys, a writer ‘with a particular interest in art that engages with environmental questions’, sets out in this book to examine the sway that the white birch holds over Russia — as a symbol of nationhood, power, romance, nature, politics and art. But more than that, it’s the ever-shifting notion of what the white birch — and Russia itself — represents that is most captivating here. As Jeffreys delves deeper and deeper, unravelling the glaring contradictions he’s confronted with, his statement at the end of the book’s introduction begins to resonate more: ‘Somewhere…must stand a birch that escapes the great weight of significance that Russia has given it, that I will be giving it. A birch that is simply a tree in a land that couldn’t give a shit.’

If any of you have got this far and bothered to click on any links or — heaven forfend — googled the book yourself, you might notice that this quote appears on the book jacket. Which makes me look a lazy reviewer, but honestly, I underlined it like an earnest GCSE student before looking at the back cover. And this is exactly why I love this book. Jeffreys admits he doesn’t know where he’s going at every turn, but trusts his instinct — and his ear for a good story — as he tries to untangle myth from fact.

It helps that Jeffreys knows a good catchphrase when he sees one. The book is riddled with genius pullquotes — some his own (‘the birch – a tree that is always in quotation marks’) and others lifted from the pages of history (in a 1772 letter to Voltaire, he records that Catherine the Great writes ‘Anglomania rules my plantomania’ — which sounds like The Fall’s great lost single).

But these phrases are never utilised in the stead of good old-fashioned leg work: Jeffreys braves the local trains and the art fairs in his quest to understand the contradictions of Russian identity, and how the birch is inextricably linked with that confusion. He notes, tongue firmly pushing through his cheek, how Russian brides pose against forests of birches to advertise their national purity whilst trying to escape it all for a life in the West. Or how — as Catherine the Great articulated so perfectly — Anglomania replaced Francophilia in Tsarist planting patterns. This is no small thing by the way — the formal gardens of Versailles giving way to the organized celebration of the wild ‘English landscape style’ of the 18th century.

This is where the white birch — native to vast swathes of Russia (although not, as it transpires, Moscow) starts to exert its influence. The ruling classes of Europe were beginning to embrace the wilderness — ironically fuelled by English garden designers. (As Jeffreys explains, the call of the wild developed first in England because they had cleared their forests of boars, bears and wolves, where France and Russia had not). Jeffreys notes the subtle ways in which the liberty this represents is always firmly controlled, with the white birch becoming weaponised — all too often a symbol of oppression dressed up as freedom. Thus the idea of ‘Rus in Urbe’ holds menacing connotations, as paradox is piled upon paradox. Rewilding in Russia is a very modern occurance — and yet there is a parallel drive where progress means the Urbe replacing the Rus. Coincidentally, Jeffreys notes how those who identify as ‘pure’ Russians use the Slavic term ‘Rus’ to emphasis their heritage, appealing to an idea of the mother country that is at odds with modernisation. (As is also spelt out on the book jacket: ‘the birch has its share of horrors (white, straight, native, pure: how could it not?’) — and since several former Soviet countries adopt the birch as a national symbol, its meaning shifts with the political map.)

This is the great joy of Jeffreys’ book — and of his writing in general. He sets out his stall and then — aware of the petards he’s hoisted for himself — debunks his grand aims. But, rather than an admission of defeat, it’s an acceptance that the subject he’s taken on is far too nuanced for one grand unified theory. The birch, he points out, is an umbrella term for numerous species that are often confused. Like Russia itself, it defies scrutiny because everyone has a different definition of it. Even its role as shorthand for ‘eternal Russia’ is thrown into doubt, since the lifecycle of the birch is incredibly short compared to many species.

You can’t deny Jeffreys’ commitment to the cause — his journey takes us from Peter the Great to Pussy Riot (who he dismisses as shallow situationists until one of them is poisoned by Putin loyalists); from the formal dachas of St Petersburg and the Potemkin villages of the Ukraine to the irradiated wastelands of Chernobyl.

Here, the book’s theme starts to emerge more fully — although Jeffreys is typically self-deprecating even as it does (‘Like an idiot, I went to Chernobyl with a clear idea. It didn’t take long to unravel’). The most striking image he conveys is that of an empty guest room in the Polissia Hotel, with a birch tree growing through the floor. Over the years, the room becomes more enveloped in vegetation. It’s hard to avoid metaphor when it’s staring you in the face like this. Russia can change. Modernisation can come and go. But nature endures. Decay is subsumed by growth.

This image also supports his theory that white birches are the shock troops of horticulture, spreading their seeds far and wide and germinating in soil that is too lacking in nutrients for other species. In a lovely moment, he notes how the Russian trend for lining streets with birches is actually an imitation of natural life: because birches naturally seed in recently disturbed soil, they tend to spring up along the roadside anyway, as new routes (and New Deals) are formed.

Jeffreys’ quest to know more about Russia ends with an acceptance that it might ultimately unknowable — and is all the better for it.

*

‘The White Birch: A Russian Reflection’ is out now and available here (£15.79), published by Corsair.

Mark Hooper is the author of ‘The Great British Tree Biography’, published by Pavilion.