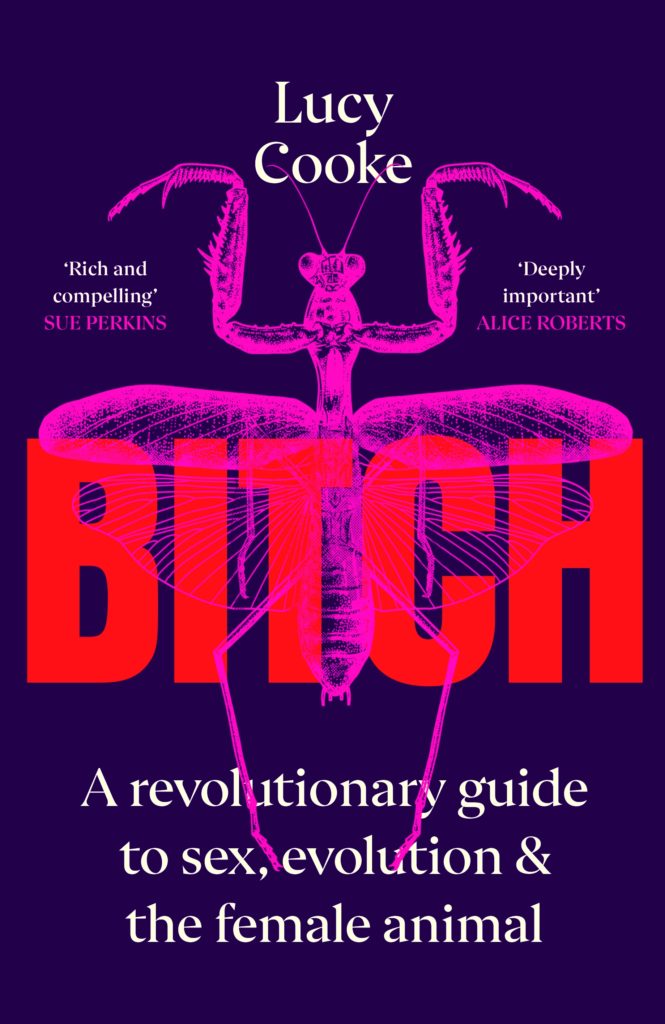

An edited extract from Lucy Cooke’s revolutionary guide to sex, evolution and the female animal, published earlier this month by Doubleday.

Studying zoology made me feel like a sad misfit. Not because I loved spiders, enjoyed cutting up dead things I’d found by the side of road or would gladly root around in animal faeces for clues as to what their owner had eaten. All my fellow students shared the same curious kinks, so there was no shame there. No, the source of my disquiet was my sex. Being female meant just one thing: I was a loser.

‘The female is exploited, and the fundamental evolutionary basis for the exploitation is the fact that eggs are larger than sperms,’ wrote my college tutor Richard Dawkins in his bestselling evolutionary bible, The Selfish Gene.

According to zoological law, we egg-makers had been betrayed by our bulky gametes. By investing our genetic legacy in a few nutrient-rich ova, rather than millions of mobile sperm, our forebears had pulled the short straw in the primeval lottery of life. Now we were doomed to play second fiddle to the sperm-shooters for all eternity; a feminine footnote to the macho main event.

I was taught that this apparently trivial disparity in our sex cells laid cast-iron biological foundations for sexual inequality. ‘It is possible to interpret all other differences between the sexes as stemming from this one basic difference,’ Dawkins told us. ‘Female exploitation begins here.’

Male animals led swashbuckling lives of thrusting agency. They fought one another over leadership or possession of females. They shagged around indiscriminately, propelled by a biological imperative to spread their seed far and wide. And they were socially dominant; where males led, females meekly followed. A female’s role was as selfless mother, naturally; as such, maternal efforts were deemed all alike: we had zero competitive edge. Sex was a duty rather than a drive.

And as far as evolution was concerned it was males who drove the bus of change. We females could hop on for a ride thanks to shared DNA, as long as we promised to keep nice and quiet.

As an egg-making student of evolution, I couldn’t see my reflection in this fifties sitcom of sex roles. Was I some kind of female aberration?

The answer, thankfully, is no.

A sexist mythology has been baked into biology, and it distorts the way we perceive female animals. In the natural world female form and role varies wildly to encompass a fascinating spectrum of anatomies and behaviours. Yes, the doting mother is among them, but so is the jacana bird that abandons her eggs and leaves them to a harem of cuckolded males to raise. Females can be faithful, but only 7 per cent of species are sexually monogamous, which leaves a lot of philandering females seeking sex with multiple partners. Not all animal societies are dominated by males by any means; alpha females have evolved across a variety of classes and their authority ranges from benevolent (bonobos) to brutal (bees). Females can compete with each other as viciously as males: topi antelope engage in fierce battles with huge horns for access to the best males, and meerkat matriarchs are the most murderous animals on the planet, killing their competitors’ babies and suppressing their reproduction. Then there are the femme fatales: cannibalistic female spiders that consume their lovers as post- or even pre-coital snacks and ‘lesbian’ lizards that have lost the need for males altogether and reproduce solely by cloning.

In the last few decades there has been a revolution in our understanding of what it means to be female. This book is about that revolution. In it, I will introduce you to a riotous cast of remarkable female animals, and the scientists that study them, who together have redefined not just the female of the species, but the very forces that shape evolution.

***

Seduction is an awkward game for many males. The stakes are high, as is the suitor’s vulnerability. Timing, technique and a certain amount of chutzpah are all required to secure success. But when the object of your desire is a ferocious predator that eats animals that look like you for breakfast, finding a mate becomes a dance with death.

This is particularly true in the case of the male golden orb weaver spider (Nephila pilipes). The female is Goliath to his David; around 125 times his mass and armed with giant fangs that deliver a potent venom. To seduce her, the male must gingerly traverse her enormous web – a succession of tripwires designed to sense the slightest vibration – then clamber on board her gargantuan body and copulate, all without triggering her hairpin attacking instinct. His chances of running this sexual gauntlet with life and limb intact are slim at best. For the male golden orb weaver spider sexual disappointment takes the form of a grisly death, his would-be lover literally sucking the life out of him in a matter of minutes, before hurling his desiccated carcass on to the burgeoning heap of failed suitors below.

News of such shocking female behaviour did not escape the attention of Darwin, although his handling of the horror is highly euphemistic. In The Descent of Man he details how the male spider is often smaller than the female, ‘sometimes to an extraordinary degree’ and must be extremely cautious in making his ‘advances’, since the female often ‘carries her coyness to a dangerous pitch’, which is, I suppose, one way of putting it.

Darwin’s androcentric account eventually dares to spell it out by noting how a fellow zoologist by the name of De Geer saw a male that ‘in the midst of his preparatory caresses was seized by the object of his attentions, enveloped by her in a web and then devoured, a sight which, as he adds, filled him with horror and indignation’.

The female spider’s penchant for rolling dinner and date into one was an affront to male Victorian zoologists on several counts. Here was a female that deviated from the passive, coy and monogamous template by being vicious, promiscuous and unquestionably dominant. She also represented something of an evolutionary conundrum. If the point of life is to pass on your genes to the next generation, then eating your potential sexual partner instead of mating with him seems maladaptive. Yet sexual cannibalism is common amongst spiders of all kinds, along with a host of other invertebrates, from scorpions to nudibranchs to octopus. The most famous is probably the praying mantis, a femme fatale who devours her lover’s decapitated head, while his truncated body continues to valiantly thrust away behind. The existence of such behaviours has prompted generations of (mostly male) zoologists to suppose that evolution itself has lost its head.

In Darwin’s time reproduction was assumed to be a harmonious affair with both sexes cooperating to create the next generation. This romantic notion seems rather quaint today. In the last few decades we’ve begun to appreciate how females and males across the animal kingdom frequently have incompatible sexual agendas. Love is a battlefield and sexual conflict is now understood to be a major evolutionary force that works antagonistically between the sexes. The tug of war of opposing interests provokes an evolutionary arms race of adaptations and counter-adaptations as each sex tries to outfox the other and get what they want.

Nowhere is this sexual conflict more extreme than among spiders. The possibility of cannibalism places the ultimate selection pressure on the male to evolve creative solutions to counter the lethal threat of a hungry female.

At the most basic level, many orb weaver males have learned to wait patiently at the edge of the female’s web until their paramour is consuming her lunch, possibly one of their love rivals, before making their move. Others, like the male black widow, can actually smell if their fancy is hungry from the sex pheromones on her silk, and keep a wide berth if she is. Then there are those that arrive on their date lugging dead things wrapped in silk – the spider equivalent of a box of fancy chocolates – to occupy the female’s jaws while the male gets down to business with his palps.

So far, so sensible. But evolution didn’t stop at the male spider simply monitoring the female’s digestive state. Sexual conflict has endowed many males with more devious manoeuvres, and as a result furnished spiders with the kind of sex lives that would make even Christian Grey blush.

*

BITCH is out now and available here (£20).

Lucy will read from and discuss the book as part of our lineup for this year’s Camp Good Life.