Writer and musician Arun Sood introduces his new album and accompanying book; an exploration of place, art, and ancestry centred on the deserted Outer Hebridean island of Vallay.

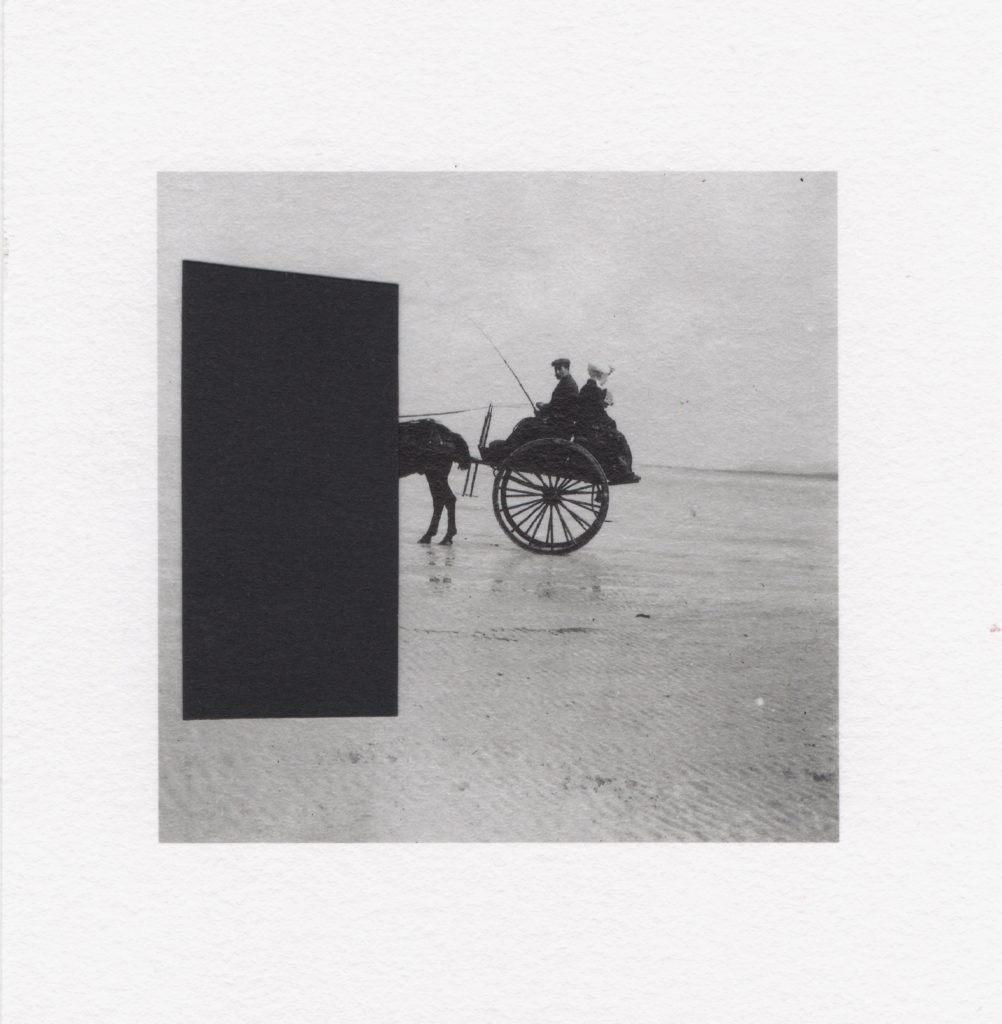

Collage by Emile Kees

It began with sounds. It began with stories.

My grandmother polishing 365 windows. Brightly-tiled fireplaces. Fresh water piped in from the mainland. The drowning of George. Cèilidhs at dusk. Skirt hiked to knees. Wet socks. The leaving. The longing. The tides.

These stories of Vallay. These people. These pasts. These sounds.

Vallay is now uninhabited by humans. My grandmother was one of the last to leave, and a strong ancestral current has pulled me back, physically and imaginatively, over a period of many years.

Vallay lies approximately two miles off the Northwest coast of North Uist, the Outer Hebrides. On foot, it can only be accessed from North Uist for a limited time at low tide, across vast tidal sands which quickly flood with saltwater that gushes in from the Atlantic, cutting it off from the ‘mainland’. A central figure in the island’s history is Erskine Beveridge (1851-1920) — a textile manufacturer turned antiquarian, photographer and archaeologist. Beveridge’s textile business funded his travels throughout Scotland, and his wanderings with a camera led to the publication of several books on Scottish history and archaeology. Most notable were his archaeological excavations in the Outer Hebrides which he conducted from an Edwardian mansion which he built on Vallay in 1905.

Beveridge’s mansion was lavish, even extravagant, in its Edwardian heyday. Colourful fireplaces graced every room, fresh water was piped in from the mainland, and it was said that exactly 365 panes of glass were used to populate the ornate window frames. As Fraser Macdonald notes in his essay ‘The Ruins of Erskine Beveridge’:

This ample provision should be understood in the context of its [Vallay’s] remoteness: every brick and beam needed to be brought in by steamer and, depending on tides, offloaded on the shore for its final journey by horse and cart to the house site. Even the soil for the garden was imported by boat. These materials, once so carefully selected, transported and arranged, are now subject to the same ecological decay that buried Beveridge’s cherished Earth-houses. Taigh Mor is a ruin. Its ruination continues with every passing year, bringing down a few more bricks, rafters, floor boards and roof-tiles.[i]

Beveridge’s mansion gradually fell into disrepair after his son George drowned in 1944 while crossing the strand at high tide; leaving no heir nor work for the small population of crofters, groundsmen, and housekeepers who departed the island shortly after. My grandmother was among them.

Since 2011, I’ve responded to Vallay through poetry, essays, and taken many photographs. But sound became integral to mediating a sense of connection with the place and its past. I recorded island descendants. Flapping pigeons. Gull shrieks. Rumbles of wind. Lapping tides. Atlantic howls. I set these sounds against newly composed musical responses to the island and its histories and recorded spoken word poetry.

Collage by Emile Kees

Sometimes, I grasped on to the coattails of a story and let the sounds reverberate themselves. There’s an oral account that says the night before his passing, the last person born on Vallay woke to sing an acapella rendition of Donald Ross’s Gaelic lament ‘Cailin Mo Rùinsa’. The last song, from the lastborn. Fragments of the song feature in different spectral iterations throughout Searching Erskine. ‘He Was Drowned’ (a requiem for George Beveridge) is based around four chord changes from the song, set to background murmurs of its down-pitched lyrics. ‘Lachlan’s Drones’ features a synthesized chanter playing a fragment of verse, set to my spoken re-telling of the story; and ‘Above, An Abandoned Piano Plays’ follows delayed reverberations of the chorus, set to recorded conversations about the lastborn. The album closes with a guest contribution from Rachel Sermanni, who sings a full and translated rendition of the song, set to field recordings of the lapping Vallay tides.

Other tracks began were sonoric happenstance; ‘The Old Dictaphone’ being a case in point. I was on my way to Vallay to do some field recordings in 2019. I stopped at my cousin Myra’s croft on Harris. Myra’s father, Lachlan, had also lived on Vallay, so we spent the afternoon chatting between drams and biscuits and cheese. Lots of recollections, songs, myths and memories. Myra sang Gaelic songs, her husband Scott had a tune on the small pipes before playing tapes on a cassette player that doubled as a dictaphone. I recorded most of the afternoon, but when I came to listen back was haunted by the ghostly fragment of the song ‘An t-Eilean mu Thuath’ (‘Isle of the North’) I had inadvertently captured. I looped the fragment and wrote the morose piano riff quickly after. The spoken word at the end is taken from a passage of Erskine Beveridge’s book North Uist (1911), but my favourite part of the track is Scott’s background murmurs about his old dictaphone. The looping of ancestral songs and whispers throughout feels tidal to me.

Most of the time, I didn’t know what I was doing. But I knew sound was doing something to me, and I was doing something to sound.

Reading the German literary scholar Helmut Kaffenberger helped my understanding. Kaffenberger describes the concept of an “acoustics of profane illumination”[ii], whereby seemingly accidental or inconsequential sounds can prompt transcendental memory recall. Kaffenberger describes how mundane sounds — buzzing, chirping, droning, rumbling — can inaugurate dream-like experiences and collapse temporalities, bringing the past into dialogue with the present in transformative ways. These sonic “profane illuminations”, or “rememories”, bring us into contact with the past — even if there is no tangible sense of having physically been there. Mirko M. Hall has further described the mnemonic function of sound in its capacity to recover “long-forgotten traces of past experiences”.[iii] Thus, the sounds of a specific site or place become an excavation site, whereby acoustic ruins can be retrieved and reassembled to provide a “mode of knowledge that often exceeds logical categories of perception”.[iv]

Like Beveridge’s excavations, my own recordings attempt to forge connections with Vallay’s past. The tracks blast acoustic phenomena out of their geographical and historical contexts; alter them; distort them; loop them; and reconfigure them into new constellations that explode the reified past.

The process of liberating the rumble of wind, roar of ocean, and birdsong from Vallay and rearranging them into new compositions allows for a recontextualisation that transforms the past. That is, the sounds of place become a courier for past histories and peoples to be revealed, remembered, and redeemed…

These explorations in sound have also led to fruitful collaborations with visual artists working on the intersections between art, ancestry, and place. The accompanying book to the album features visual artworks from Emile Kees, Rosalind Blake and Meg Rodger. Emile’s archival collages look at a series of moments that took place on Vallay, altered by new textures and colours. Memory transformed. Rosalind’s two-plate monoprints reflect on the experience of Vallay as a space of layered history: both human and non-human. Formal elements draw on the architectural, aesthetic, and experiential qualities of the tidal island, while colour and movement communicate the ineffable sense of flow, flux and rhythmic fluidity. Meg’s ‘Neolithic Skyscape’ drawings explore how the sky, particularly at night, is a vast and constant system that links us with our ancestors.

I have been very fortunate to collaborate with these artists in my own sonic exploration of place, art, and ancestry. Their works will be exhibited for the first time at Taigh Chearsabhagh Museum & Arts Centre on the day the album is released (05.02.22), along with a new interactive sound installation I have created entirely out of synthesised field recordings from Vallay.

It began with sounds. It began with stories.

*

[i] Fraser Macdonald, ‘The Ruins of Erskine Beveridge’. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12042: 478.

[ii] Helmut Kaffenberger, ‘Aspekte von Bildlichkeit in den Denkbildern Walter Benjamins’ in Global Benjamin: Internationaler Walter-Benjamin-Kongreß, ed. Klaus Garber and Ludger Rehm, 3 vols. (Munich, 1999), 460.

[iii] Mirko M Hall, ‘Dialectical Sonority: Walter Benjamin’s Acoustics of Profane Illumination’. Telos: Crticial Theory of the Contemporary 152 (2010): 86.

[iv] Ibid.

*

Tommy Perman writes:

“I’ve been lucky to have a copy of Arun’s Searching Erskine album for a while now. Over repeated listens I’ve enjoyed discovering new details gradually emerging from the rich layers of sound. I’ve tried to represent this experience in the video for The Old Dictaphone. I took my portable projector to a beach and beamed some of Arun’s collection of archival photographs, films and maps onto waves lapping at the shore — the water, sand and stones refracting and distorting but also revealing memories of Vallay.”

Watch the video below.

*

The ‘Searching Erskine’ digital album and book will be released tomorrow on Bandcamp via Blackford Hill, with a special lathe-cut 7″ edition coming soon. Read more about the project here.

The accompanying exhibition opens at Taigh Chearsabhagh Museum and Arts Centre, North Uist, this Saturday. More information here.