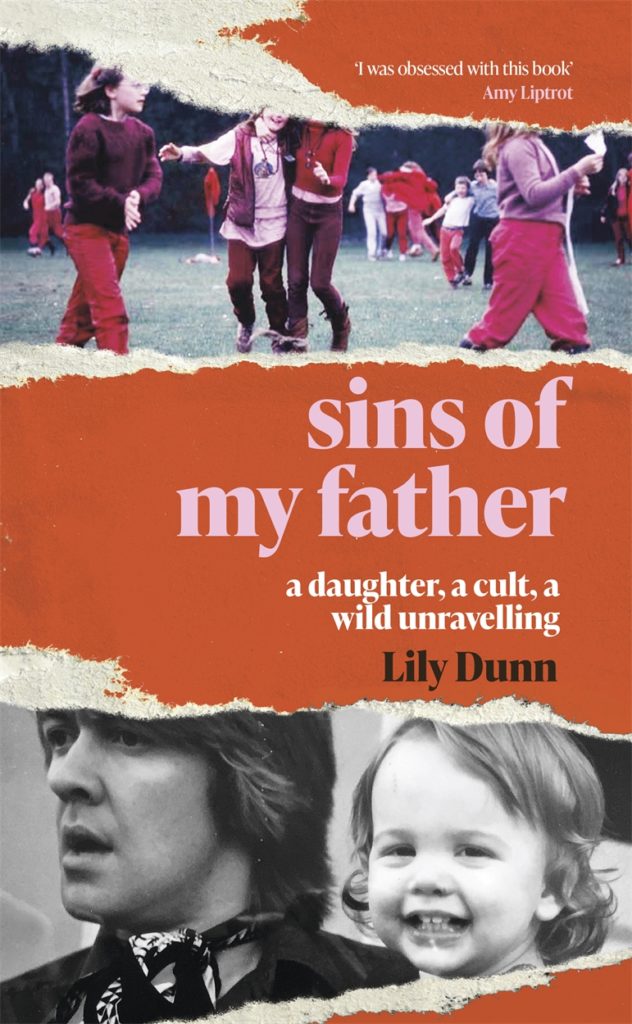

Lily Dunn’s ‘Sins of my Father: A daughter, a cult, a wild unravelling’, published yesterday by Weidenfeld & Nicolson, is a startlingly self-assured debut memoir, and a notable addition to the canon of work on cults and high-control groups, writes Ali Millar.

Sins of my Father: A daughter, a cult, a wild unravelling is a book about Lily Dunn’s father, a writer and publisher who remains nameless throughout, telling how he leaves the family home when Dunn’s six and her brother eight, lured by the glow of Bhagwan Rajneesh, quickly becoming embroiled in sannyasin life.

In many ways, Dunn’s Sins of my Father opens at the beginning of the end, with Dunn imagining the events exacerbating her father’s untimely demise; a technique employed with great poignancy at key moments in the book. From the outset the reader is fully aware the story leads to Dunn’s father’s early death, his body wrecked by many years of alcoholism and neglect. This stirs empathy for a man who otherwise would be nearly impossible to like or understand. Dunn’s compassionate telling of a harrowing story provokes far more than a knee-jerk reaction; we are invited into the world she shares with her father, and what unfolds is a story of a difficult man and the wreckage he leaves in his wake.

For the most part Dunn is a clear-eyed narrator unflinchingly exploring her Father’s attraction to the cult, going beyond any obvious appeal of the sannyasin movement, drawing a line between her father’s early years at boarding school and the sexual abuse he suffers as a child to explain why the cult appeals so deeply to him. Life as a sannyasin absolves him of responsibility — he can access sex with whoever he wants whenever he desires — and presents a cultural alternative to the humdrum safety of north London. But before being drawn to the cult, he’s already a ‘serial shagger’, having an affair with the midwife assisting at Dunn’s birth. He later boasts to his sister that throughout the course of his marriage he’s slept with more than 500 other people. The cult perhaps is simply the excuse he’s been looking for to indulge his every desire, and way out of a life he clearly feels beneath him. This allows for an examination of the darker elements of cults, asking what they fulfil in followers and how they tap into desires for elevation, escape and absolution. The cult plays an impactful but limited role in Dunn’s father’s life; when he leaves, his disdain for normalcy is no less apparent. He is still on a mission for a life less ordinary — a quest that leads to his downfall.

At first, Dunn is sheltered from the full effects of sannyasin life, but when the ashram comes to Suffolk, she is exposed to the whole force of it. She yearns to be part of them, but she is neither fully a child of the cult or a child of north London. It is this inside/outside perspective that’s the real strength of the book, allowing it to become a work of both biography and autobiography, telling the story of the charismatic father, but also of the effect his dereliction of duty has on those left behind. There is repeatedly the sense of Dunn as both participant and observer, first as a child and then as the adult narrator, fully inhabiting the perspectives of each of her parents.

Personal freedom always carries within it its own cost. Sins of my Father presents these, examining the long-reaching effects of a parent who’s absent even when present, and present when absent — he is never not overbearing, yet never gives himself fully to Dunn, her brother, or her mother, or to anyone else; he refuses to or is unable to commit. The most shocking parts of the book are the direct interactions Dunn has with her father. At the age of 13 she’s groomed at his house by a man who’s 38. A man her father initially encourages her to sleep with, only conceding when he discovers the man has gonorrhoea, saying ‘it’s probably best you don’t have sex with him’. Later, when she falls off her moped while out riding alone, her injuries are left untreated. All of this is presented to the reader in the calmest of tones; there is no narrative judgement. This is a story about facts: Dunn doesn’t invite pity.

Throughout, Dunn’s mother presents a comforting counterpoint to her father’s actions. She swiftly picks the family up after they’re left, prevents outright financial disaster, tends to the children, and constantly pieces Dunn back together again, both physically and emotionally. Here is an eminently smart woman, allowing just enough of their father into the children’s lives so they later can draw their own conclusions about him, understanding that to do otherwise would run the risk of turning him into a ‘messianic mystery’.

It is perhaps the level of care and attention to Dunn’s subject that leads to the only problem with the book. So many complex themes invite questions of inheritance and the fear thereof, personal freedom and choice, with Dunn deftly examining what these mean in relation to her own life but neglecting to consider the same for her father. Here her father runs the danger of becoming the cult figure with Dunn giving obeisance; a little more interrogation of her father’s capacity for choice would go a long way. However, it also seems as though Dunn is cognisant of this failing and uses it to dramatise the difficulty of removing herself from such a manipulative and deeply confusing relationship.

Sins of my Father is robustly researched. Dunn is a writer coming to terms not only with her father, but with memoir itself, pushing the bounds of its form to create a book that’s a notable addition not only to work on cults and high-control groups, but also to family biography. While most of the extant literature on cults is from an insider’s perspective, Sins of my Father is of immeasurable value in that it highlights how those left behind are affected, showing the far-reaching impact of cults on anyone drawn into their orbit.

At its most tender and difficult, Sins of my Father is really about the near intractable impossibility of moving beyond childhood trauma to transform a damaging legacy into something positive — and this is exactly what Dunn achieves with this remarkable book.

*

‘Sins of my Father’ is out now and available here (£15.79).

Ali Millar is the author of ‘The Last Days: A memoir of faith, desire and freedom’ (Ebury, July 2022) about life in, and beyond, the Jehovah’s Witnesses. Born in Edinburgh, she lives in London. She is working on her second book.