Nick Hayes’ s ‘The Trespasser’s Companion’ — the follow-up to last year’s groundbreaking ‘Book of Trespass’ — is newly published by Bloomsbury. Mathew Clayton catches up with the Right to Roam campaigner and illustrator, and the two talk cotching, fence-hopping, and 1930s utopias.

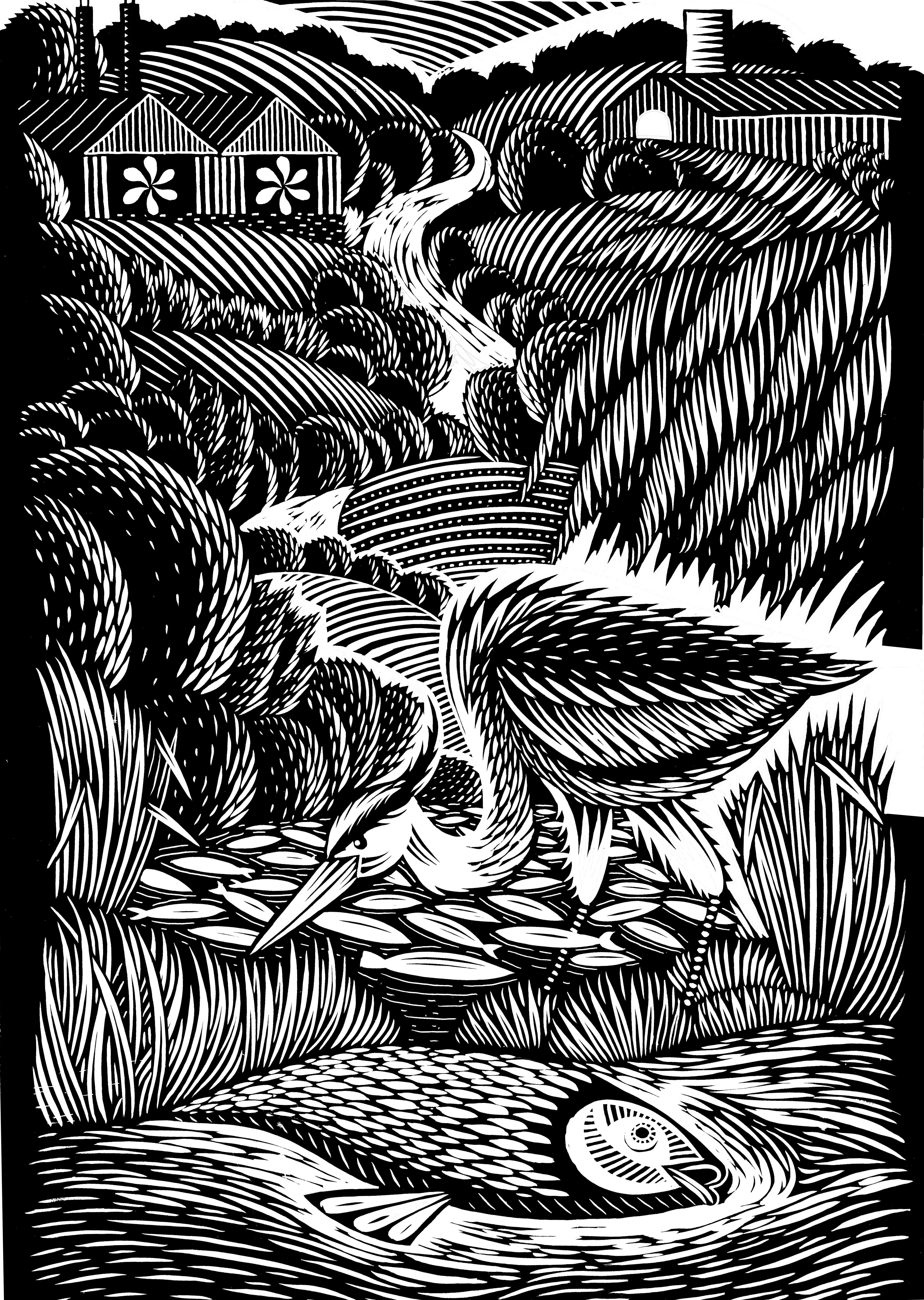

Illustration: Nick Hayes

What are you up to today Nick?

In about two hours I am going to walk up to my friend’s sheep fields and stay in a tent overnight and hopefully get a few lambs if we are lucky. There are about five more ewes waiting to drop.

Do you have to help them on the way or just be there in case anything goes wrong?

That’s all for my friend to do. I will be trying to get out of the way and make sure I am not ruining anything. It’s all about whether you see a nose or a hoof. If you see a nose you are probably alright but if you see a hoof that’s trouble. So we will be keeping our eyes peeled on various sheep’s vaginas tonight.

How did you get into art? Where you into it as a teenager?

I first got into art, less for the art, more that it gave you something to do when you are out and about. I am less of walker and more of a cotcher — I like to cotch, which is a Reading neologism for doing fuck all. I began sketching because I wanted a practice, just something to do. And you get better at it the more you do it. If you are not fussed about what other people think about your crap pictures eventually you make the pictures that are not crap. So that is where it started.

What materials were you using?

I was using a biro! My godmother had a load of defunct Leyland headed notepaper — so I would just take that and draw on the back.

Did you go to art college?

I did English at university and then I did art foundation. But I realised what you need is time. And doing an art degree is a very expense way of buying yourself time. Moral time as well — so it feels ok to be spending time doing this. So my real art degree was not at college. After my first graphic novel came out I gave myself three years to move from just doing communication in the charity sector to establishing myself in some way as an artist. I gave myself the length of time for a uni course. And after those three years I was still incredibly poor but I had sort of developed a style. I knew I was heading somewhere with it.

When did you think that your personal style was in reach?

Style is really interesting. It’s like a fingerprint, a lot of the time I didn’t think I had a style I was just being a magpie but, of course, you filter stuff that you like — Eric Ravilious, Stanley Donwood. Artists that are my heroes. You copy them but because you are not good enough to copy them precisely it inevitably comes out in your own way. And then after a while you step back and look at old drawing books and suddenly you see what your friends were going about. You have a style. I think the key to being a professional illustrator is to work out what that style is and try and make the most of it. But the problem then is you become a better illustrator but a worse artist because you just replicate the same old thing. That’s what gets you money as an illustrator but that’s what stagnates you as an artist.

It’s the Ramones problem!

Yes. A lot of bands go through that. With Radiohead after OK Computer they were supposed to write OK Computer 2 but Kid A shoved a finger up to everyone. Most of my heroes are musical.

Who are your illustrator heroes?

Eric Ravilious is a big one. Woodcuts and wood engraving in general, they evoke an old English 1930s utopia that never existed — the style is a sort of surrealist pastoralism. It is a pretty chocolate box except then there will be a weird shadow across it. They have a certain atmosphere, I’m thinking of people like Paul Nash, David Nash, Eric Bawden. And Eric Gill (although he was a dog-fucking incestophile).

Why do you think wood engraving is so good at evoking English countryside? Is it just because it is easy to do leaves? Why does it work as a style?

I don’t necessarily know if wood engraving is suited to the topography and landscape of England but I certainly has helped to build our pastoral image. In some ways it feels like a good way to capture England simply because our notion of England has previously been captured by it. It is the visual version of Edward Thomas or Thomas Hardy. A lot of the 1930s nature books were illustrated and books by people like Gilbert White. But maybe it was just the 1930s wave of nature writing happily coincided with this new wave of woodcut artists — the ones I am keen on.

I’m also inclined to say it is to do with smallness. There is something about English landscape that is quite contained and quite twee. It is about the bristling of the oak tree as it is about the wide vistas (like you would find in America). You can convey the line of a leaf with just two digs that meet in the middle like a V.

What technique do you use?

I have done lino and wood cuts. I haven’t done wood engraving but it is my ambition, when all this campaigning is done, to learn. The things I have been doing recently are fake lino cutting. I use a brush and ink and it is done in relief — so every mark that would be white is a mark that I have made on the page. And then I just use Photoshop to invert it. I started off doing lino cut illustrations but the cost of printing and the time it took was prohibitive. I don’t know how previous wood engravers managed to do their stuff. I doubt they were paid relatively more than I am. Illustration is just a trade. Here’s the job that needs to be done. You are not getting paid to do anything other than fill space and prettify things.

When did you start getting involved in trespassing?

With drawing really. They are parallel threads. I used to just nip over the fence to draw. If I saw a fallen oak tree but there was barbed wire in the way I would just nip over. I would be sat there drawing and the gamekeeper or the young lad on a motocross bike would be sent over to be aggressive. Their response to me seemed totally disproportionate to what I was doing. They couldn’t really see what I was doing. And that was so interesting. What lenses are they seeing me through? To everyone it looks like I am sat on my arse drawing but not to them. So eventually I looked into it.

What was the most surprising thing that you discovered?

Rivers are absurd. We are allowed access only to the rivers that have had a specific right of boating navigation that was applied to them in the Georgian era. It is only 3% of English rivers. You have no permission to swim in the other 97%. And the aggression on the river is so incongruous to the river itself. They are super chilled places. We are campaigning for a less misanthropic English countryside in a nutshell.

Where does that tradition of Get Off My Land come from? How far back can you trace it?

It’s William the Conqueror and his forests. These new spaces that he created that were outside of common law. They took up a fifth of England. There was private property before but it was the notion of exclusive ownership that was new. Total dominion over the other people that relied on that bit of land.

And rich people just got richer. You can lend money with land as your collateral. As long as you own land you can be a rich person. And then land became an investment rather than a resource. And it has just been getting tighter and tighter every century.

And is it easy to find who owns land?

No, it’s almost impossible. In Montana or France you can look up who owns land by going into your town hall or going online. Here you have to pay £3 per tiny plot. The plot can be an acre. Guy Shrubsole worked out you would have to spend £71 million pounds to find out who owns England. And even then you wouldn’t find everything out because 15% of England is unknown because 15% of land hasn’t changed hands since the 1900s — before the land registry started.

It’s mental, but we are all so used to it no-one ever questions it. The moment you do, that’s the moment it collapses. We are not letting the conversation end and the conversation will be the thing that kills total dominion of land.

Explain to me what total dominion means?

It means you have the right to destroy it. Exclude people from it, mine it, do what you like. The right to turn a thriving wildflower meadow into a dead monoculture of wheat. This is why our natural habitats have been so badly exploited.

When did you realise that these ideas where connecting with other people?

Me and Guy Shrubsole are known just because of our books but the movement has been going on for a long time. We met as part of a land justice network. But we are neither the leaders or the most worthwhile spokespersons. There are much wiser people involved.

When lockdown happened people remembered how special it was to send time in nature as it was the only hour they had out of their house. But they also got bored walking the same three rights of way. What about that patch of woodland just over there? The funny thing is that you start to appreciate farmers more if you trespass. I go out at seven in the morning and come home at seven at night. And the same farmers are in the same fields doing the same thing. You get a sense of the relentlessness of the trade. So we really think that community interaction with the countryside would allow us to appreciate how valuable the farming community is to us.

And have you had any support from farmers?

There lots of famers that would encourage people to be on their land. But it is crucial that you do a few things: keep your dogs on leads when required, not drop litter, leave gates as you find them. These are really important. If we could guarantee these things then there are early indicators are the farming community would be supportive.

How can one get involved?

Going to Right to Roam and signing up is the best way to know what’s going on. On 24th April there was a people of colour march up on Kinder to celebrate what they did 90 years ago but also to show how much more needs to be done. There is loads happening and people are encouraged to join in.

What other books wold you recommend?

Guy Shrubsole’s Who Owns England? is the companion piece to The Book of Trespass. A Right to Roam by Marion Shoard, Peter Linebaugh’s Stop, Thief, Guy Standing’s Plunder of the Commons. There is lots of radical literature that tells an alternative folk story of how the common people were robbed of the land.

*

‘The Trespasser’s Companion’ is out now and available here (£13.94).