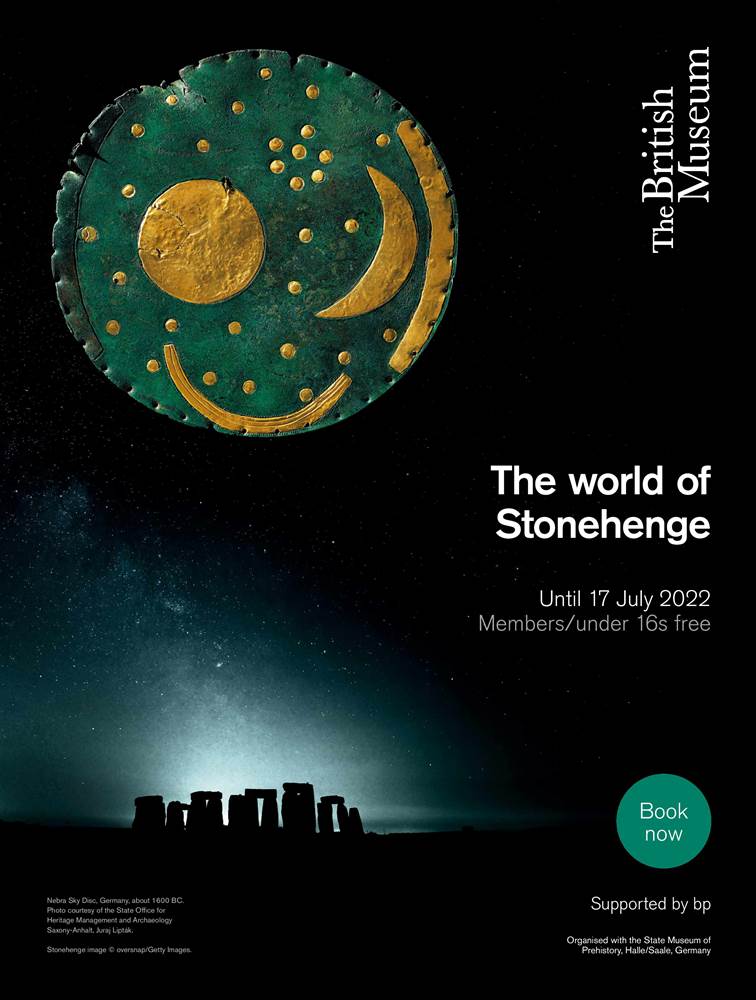

The British Museum’s ‘World of Stonehenge’ exhibition maps out a prehistoric world of ritual, movement, change and innovation, writes Anna Fleming.

5000 years ago, our ancestors dragged stones across land and sea to build a temple on Salisbury Plain marking a certain moment in the solar calendar. Stonehenge has entranced people ever since. Our lives have changed beyond recognition and yet still each year a crew gathers at the stones to mark the solstice. The temple is the omphalos but not the focus for the magnificent World of Stonehenge exhibition, which showcases a broader sweep of place and time illuminating the wider context in which these mysterious stones stand.

The finds date from 4000 to 1000 BC and were turned up from peat and soil across the British Isles, from Orkney to Wiltshire, as well as wider Europe: Ireland, France, Denmark, Sweden, Italy, Switzerland, Spain, Portugal and Romania. With a reminder at the entrance that Britain was part of mainland Europe until 6200BC (connected via low-lying Doggerland which flooded at the end of the last Ice Age), the exhibition maps out a different vision of Europe. A prehistoric world of ritual, movement, change and innovation.

In the opening cabinet, we meet an antler headdress from Bad Dürrenberg, Germany, made of roe deer, wild boar tusk, and teeth from aurochs and bison. The headdress grounds us in another ecological Europe: the auroch was a giant ox, ancestor of our domestic cattle, wiped out in 1627; wild European bison were hunted to extinction but saved by captive breeding. The headdress also transports us to another spiritual world. It was buried with a woman in a crouched position. Analysis of her skull reveals she had a rare condition which meant she would lose control of her body, slipping into trance-like states and hallucinating. She was a shaman who communicated with spirits on behalf of her people.

Another cabinet is filled with puzzling carved stone balls found across eastern Scotland. Over 400 of these strange stones have been found. Who carved them? Why? Were these finished artworks, sacred objects or merely a craftsman’s practice piece? There are no answers, only the objects. (I like to see them as the Earth in miniature, speculating to myself that perhaps long before Christopher Columbus, these early people had the measure of the world.)

A wall of gold: gold collars and gold necklaces and two absurd gold hats. The hats are gigantic, rising to 80 centimetres tall, coated with cosmological symbols including circles, solar-wheels and even a sun-like starburst. Are these calendars of the cosmos? You might expect such dazzling gold-ware in Aztec or Mayan cultures; but these were unearthed in France and Germany, providing a tantalising glimpse that the Europeans also had their share of gold-based sun-ceremonies.

Layers and fragments of sounds emanate from Seahenge, a replica ring of split-oak posts, circling around an upturned oak found on the coast of Norfolk. The soundscape brings wind, water, insects, air, looping curlew-like cries, fizzing and whispering into this room in central London. Artists Rose Ferraby and Rob St John composed half/life from recordings of flood gates, pools and sea foam in the saltmarshes. Circling this extraordinary monument, I am so curious, wanting to reach out and touch these other times, to unfold the practices of our ancestors. Why place the oak like this, at the edge of land and sea, with roots upturned, facing the heavens like branches? What kinds of movements did this inversion facilitate?

The exhibition opens as many questions as it answers, the curious objects gesturing to many astonishing ways that our European ancestors related to place, earth and the cosmos. Trying to take all of this in, the dark room spins and I see in circles and spirals, rhythms of sun and moon, cycles of time served up in great loops and circles; all of which seems so distinct from the razor-edged arrow of modernity.

But the linear channel of our present time is here too. Circling back through the treasures, I land on the wall of stone axes. The precious pieces of flint and volcanic tuff are blue, grey, green, charcoal black and burnished brown, chipped and polished to become sculptural art-work invested with great symbolic power. The stone axes are not simply art — they gesture to the development of a pivotal human technology which would have far-reaching effects.

The exhibition hinges on one of the most significant transitions in human history: the shift from hunter-gathering to farming. The Bad Dürrenberg shaman comes from the time before; most other pieces come from the time after. When farming was introduced from the continent, the practice transformed how we live, shaping our relationship with earth right up to this very heated moment. It is hard to imagine such a seismic shift, lost in the distant mists of prehistory. Yet one of the displays gives a window on the changing of those world orders. A cabinet of bones and clay shows the remains of a feast that happened near Stonehenge sometime between 3900–3800 BC. The bones belong to domestic cattle and roe deer: farmed beef and hunted venison. Peering through this glass, I witness a historic meeting of minds, the new farmers and the old hunter-gatherers, sitting together to share a meal, exchanging words and novel ideas for another way of life.

The World of Stonehenge is the first exhibition of this period of European history to appear in the British Museum. Perhaps this pre-Christian, pre-written era is too pagan, mysterious, New-Agey or unsettling for polite Brits. Yet in our unsteady present it is reassuring to visit this old material. As Europe and globalisation falters under the strains of war, energy crisis, pandemic, climate change and species loss, it feels as though we are on the cusp of change. Many are casting around for other ways of being. Shaped by the hands of our ancestors, these objects open a space to think differently. They confirm that we have not always been this way; that we have lived alternate conceptual and ecological realities. Across the exhibition, the human desire to make sense of it all is writ large; our curiosity and thirst for knowledge, connection and meaning stretches far back in time.

Beneath the wall of stone axes, one last haunting relic sits in a small glass case. Delicate and paper-like, it is intact save for a tiny tear on one of the edges. This is a leaf which fell from an elm some 6000 years ago. Gold and stone can survive unharmed in the soil over millennia, but something as fragile as a leaf? Surveying this small miracle, a wave washes over me. Elm was my first experience of species loss. Dutch elm disease decimated these trees at the time of my birth and my dad, who couldn’t bear us to grow up not knowing the elm, showed where they used to stand and produced hazy photographs to illustrate their winter silhouettes. He wanted us to know their place in the landscape, even now they were gone, wanting us to see how elm once peopled this land.

The 6000-year-old elm leaf in the glass case registers the cost of farming, alluding to the clearances, species loss and environmental degradation that followed the axe and plough. Like William Blake’s grain of sand, the leaf embodies all the more-than-human ghosts in our landscapes — the aurochs, insects, plants and animals that have disappeared as we advance and develop. The worm forgives the plough; but can the elm forgive the axe?

*

‘The World of Stonehenge’ runs at the British Museum until 17 July 2022. More information and tickets here.

Anna Fleming will read from and discuss her book ‘Time on Rock’ as part of our lineup for this year’s Camp Good Life.