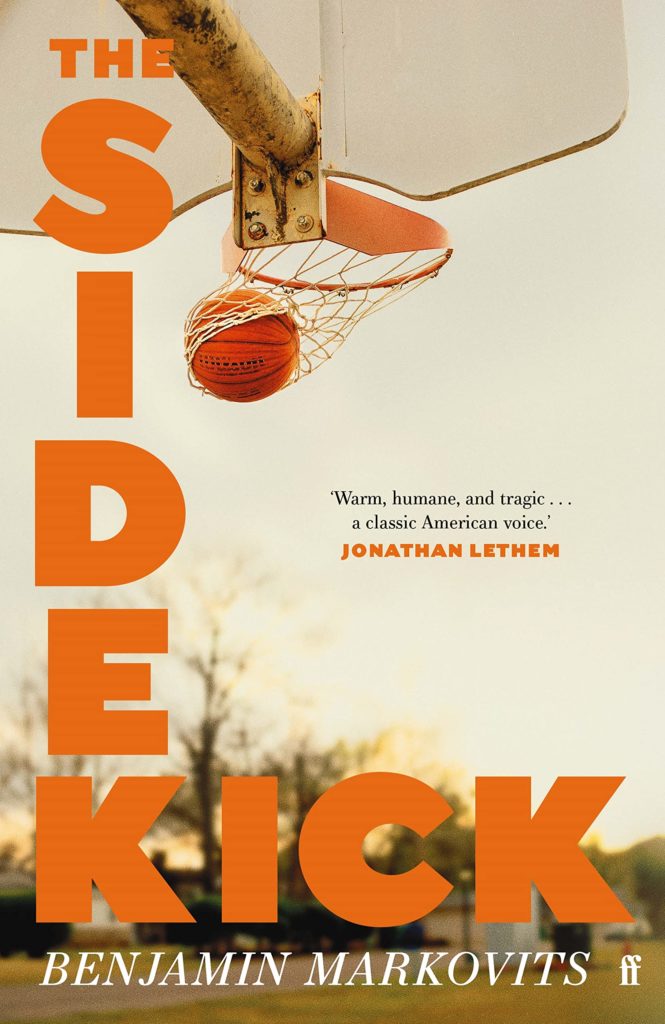

Newly published by Faber, Benjamin Markovits’ latest novel ‘The Sidekick’ is about basketball and race, friendship and envy, and the powerful divide that separates greatness from ordinary life. Will Burns reviews.

The Sidekick, Benjamin Markovits’ latest novel, starts with a description of a body, specifically a certain young boy’s body, as he sees it, and from then on, arguably, they become the book’s preeminent concern — the differences inherent in bodies, the potential, the disappointment, the miracle of them, the genetic lottery of them that allows, in fact at times facilitates, the inevitability of completely divergent life experiences. It’s a story about sport that strikes an opening note — courtesy of its narrator and perhaps its central character — about a ‘big, fat, slow kid’ and goes on to tell of that same kid’s life-long dialectical scrimmage with his childhood friend, one-time teammate, and eventual NBA superstar Marcus Hayes. Both are from Austin, Texas and they meet at the trails for their school basketball team. Our narrator is Brian Blum, an improbable high school basketball player, albeit one who merely ‘rides the pine’ (sits on the substitutes’ bench), and eventual sportswriter, whose own modestly successful career has to a certain extent been defined by his relationship with Hayes. When the pair leave high school for the same college, and Hayes begins his ascent to the NBA and stardom, Blum ‘writes him up’, as he has done since school. He has ‘access’, and despite, it turns out, having always been conscious of his own resentment towards his friend’s success and the inevitable attention that brings with it, he accepts, more or less, his own part.

The book’s tip-off is the death of Blum and Hayes’ high school coach, an incident that throws the pair together for the first time in years, in fact since Blum wrote a piece about potential corruption in the league that implicated Hayes’ then team and subsequently shut him out of the kind of access to Hayes he had once enjoyed. By then, the pair’s friendship has cooled anyway however, and through the course of the book, via flashback scenes and a timeline that jumps back and forth across phases of the boys’, and mens’, lives, we are given that friendship in all its adolescent awkwardness, its class and race dynamism, its quotidian maleness. We are told that for a time, his mother having left Austin with a new lover, Marcus Hayes moves into the Blums’ house in order to complete his education. It’s here that he starts to attract the attention of college basketball coaches and scouts, begins his transformation so to speak into a star, and here, then, where Brian’s own identity is forged in the shadow of those achievements. Brian’s father is forced to act as a kind of guardian, taking on the parental pride of Marcus’ success as well as the admin, the protectionism, even, you sense, some of the anxiety.

Around the time of their coach’s funeral, Hayes has been retired for three years, and announces a dramatic return to action, having signed for the Austin Supersonics (Markovits’ alternative universe is also full of real NBA players, coaches and franchises, but here the fiction is perhaps, and perhaps endearingly, an authorial indulgence — the once-Seattle based Supersonics franchise having relocated to the author’s home city, rather than Oklahoma as they in fact did in 2008). Hayes decides he wants Blum to write a book about his comeback. What we are presented with then, as a reader, is on one level, as Blum himself states, ‘this book’ itself, which in the writing, turns into Blum’s own (and Markovits’ own) exploration of the various pressures that might come to exert themselves on this kind of lives — American, urban, working and lower-middle class. Blum’s older sister, who may or may not have had a youthful dalliance with Hayes, has a kind of archetypal American middle class suite of headaches — a divorce, kids to feed, work to endure, nights to fill. Blum himself has the classic Fordian malaise — self-deprecatingly middle-aged at 35, obsessed with the failures of his body (and fixated as a sports nut would be on the bodies of others) and the limitations of his career. Both are looking after their ageing father, the American family unit, then, under its timeless literary pressures. For Hayes there are, and always have been, a different set of goals and snags – hangers-on, a divorce of his own, shadowy financial activities, a trail of relationships that seem to all have had some element of danger, jeopardy, secrecy. Of course all this has a racial element, the two boys’ experiences diverging along those lines throughout their lives, and not least expressed in Haye’s relationships, or potential relationships, with white girls. It’s delicately handled by Markovits, and though Blum is allowed a certain self-awareness, he’s certainly not blameless when it comes to his own reactions to events. He’s tone-deaf at times, self-centred, frustrated. In other words, he’s as mixed up as anyone, as uncertain of what’s happened, what is happening, what will happen as anyone.

The prose is clear and easygoing, at times feels almost spoken rather than written, the sentences falling on deft, authentic-feeling usages of ‘like’ and ellipsis. The strong tang of sports jargon, of technical vernacular and slang, of tactical insight all serves the text, provides a compelling kind of music, a rhythm. I could smell the gyms, could hear the squeak of basketball boots on a polished floor. Blum is a likeable, humorous presence and there is a genuine sense of jeopardy at his lifelong negotiation, now perhaps coming to a sort of final reckoning, between being a Hayes ‘sidekick’ and his desire to write the truth. The book’s evocations of the Blums’ family life and history complicate that desire, too, his father, for instance, is appalled that his son might, at this late point, commit to print a version of Hayes that he refuses to recognise, and Blum himself seems aware that his motives might not stand up to scrutiny either, but is determined to write what he believes is right, however damaging that might prove to be to his old friend. Ultimately, that is the book’s strongest suit, the strange unspoken-ness of male friendship, even love, how it can coalesce without words, or even without the expenditure of energy, and how it can dissipate just as fast, just as inexplicably. Hayes and Blum almost never tell each other how they feel, they flirt, in their way, and sulk, and talk in code, or in pointed, or cutting phrases that perhaps convey exact meaning. Markovits’ achievement is to write into that resonance all the detail and pitfalls, all the heartache and exultation, not just of sport itself, but of contemporary American life. Then again, maybe those two things have never been too far part anyway.

*

‘The Sidekick’ is out now and available here (£17.65).