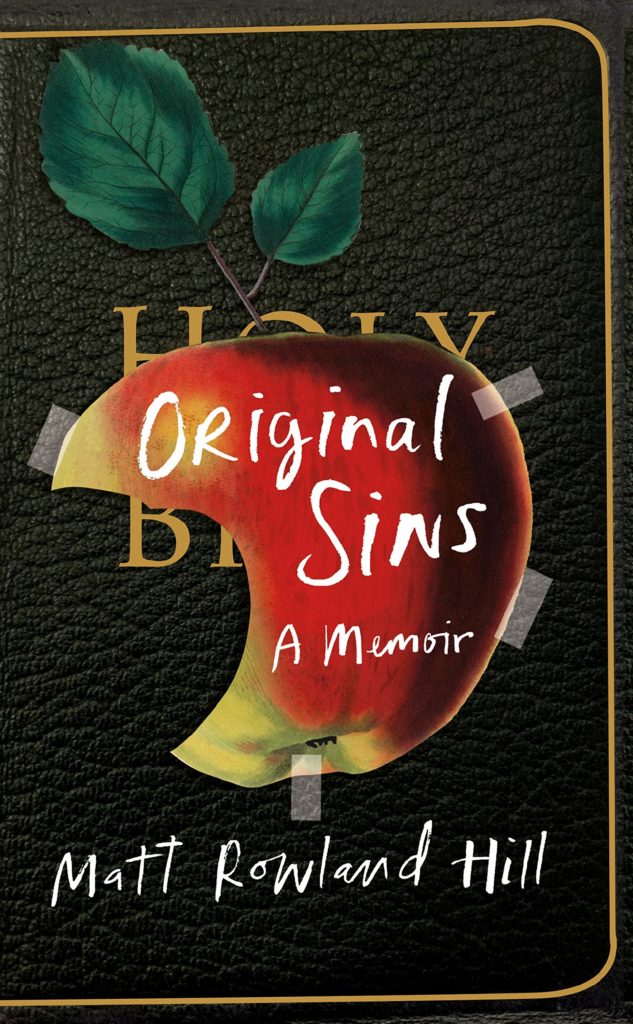

Published today by Chatto & Windus, Matt Rowland Hill’s ‘Original Sins’ explores faith, family, shame and addiction. Ali Millar reviews, finding an untriumphant memoir which is all the truer for it.

Often in memoir the narrator makes an early bid for the reader’s affections, with many authors struggling to portray themselves in an unfavourable light. Nowhere in Matt Rowland Hill’s Original Sins does this grating tendency emerge; from the outset Hill presents the glaring complexity of addiction combined with the effects of a religious childhood, painting a picture of a deeply human narrator — a strength that continues throughout the book.

The prologue opens in a bathroom — unsurprisingly there are a lot of bathrooms in the book — presented as a church-like space as the ritual of injecting the holy sacrament of heroin unfolds. This is an ecstatic moment before the kick comes: Hill’s at the funeral of a friend who’s overdosed. Immediately we’re presented with the detachment that emerges in the grips of addiction. From this opening, we’re taken back into Hill’s childhood, where religion shapes his world and young personality. Hill’s a pious child who often comes across as aloof; the question does religion make children good or insufferable emerges here, in much the same way it does in The Discomfort of Evening.

His entire reality is dominated by a Bible that’s taken literally, right down to the line ‘spare the rod and spoil the child’. When his father, a Methodist minister, half-heartedly beats him, Hill sees little distinction between God’s right hand, his father’s belt and the leather of the Bible. This unholy trinity dogs his childhood — in one scene he listens as his father preaches the story of Abraham and Isaac, viscerally imagining himself in Isaac’s position, before his father concludes the story with an ‘isn’t that amazing’. This lays bare the enduring trauma children in religious settings sustain, their parents unaware. Hill’s prowess as a storyteller is that he shapes scenes with a novelist’s eye for detail, painting both the absolute belief and sheer naivety of his parents when it comes to its effects.

Throughout his childhood and early teens, Hill places full faith in both God and his father, with each becoming the alpha and the omega, the first and last words on everything, and he remains devout until he begins to see inaccuracies in Biblical accounts. He tries to drown his emerging doubts with sex with his girlfriend Emma, promising himself that soon he will abstain, every time there’s never going to be a next time, until this deferral becomes faith itself. It doesn’t work, his whole world shatters when he wonders ‘could it really be true that everything I’d ever believed — and the whole moral worldview that went with it — was a lie? If I couldn’t trust a word my parents said, what could I be sure of?’ He hasn’t simply lost his faith in God but in the parents who fed this belief to him. When he tells his father he no longer believes in God he waits for his arms, but they don’t come; now he loses his father’s faith in him.

Hill’s at University when he first encounters heroin. Until then we’ve seen a childhood populated by difficult characters, his harassed mother in turn harasses her husband and her children; Hill wins a scholarship to a private school full of unfriendly over-privileged students, his girlfriend takes up with his friend, the first real intimacy comes the night he meets the man who becomes his dealer, the scene in which he administers heroin to Hill is one of the most tender in the book. At this point the leap from Christian to heroin user might seem a big one, but Hill explains ‘I’d long ago crossed virtually every boundary I’d been taught to fear. Since according to my parents everything that wasn’t strictly Christian was impermissible, I’d been living in a universe of taboo since I was fourteen.’ Heroin immediately offers a dual proposition; both the escape Hill needs and the transcendent experience his loss of faith has stripped from him.

As heroin becomes the best friend Hill ever had, his addiction quickly spirals. He’s a ferociously unflinching narrator, never shying away from presenting his experience of addiction. Essentially it becomes boring, his life is a series of repetitions as all he chases is his next fix. His attempts to get clean falter; the religious impulse hadn’t left. He needs ritual, belief that something else will save him from his pain, the feeling of being elect — it’s all there in addiction, and in this way Original Sins becomes an exceptionally sophisticated insight into where addiction comes from and its deeply intractable nature. In one haunting scene where Hill feeds other addicts, the distinction between religion and addiction collapses: he becomes his father dispensing the opium of the people. It raises questions of the comorbidity of addiction and religion — does religion cause addiction or is it its own addiction?

Throughout, the book is inflected with religious imagery and language highlighting the continued hangover of religious indoctrination. The only criticism would be that occasionally Hill’s narrative style veers a little close to his influences to remain distinctive, at times reminiscent of both Geoff Dyer and Rob Doyle, which isn’t a bad thing, but it quiets his voice. Some of the strongest prose comes when he employs scalpel-sharp minimalism to his sentences, making them really cut, evoking a Mary Gaitskill level of mastery.

This is a book that refuses to resolve, never settling on an easy answer to any of the questions it raises. When it grapples with faith it’s redolent of Stuart Kelly’s The Minister and the Murderer, but where Kelly intellectualises the nature of forgiveness, Hill shows what it might look like from his father’s sickbed. It’s a deeply serious book employing humour to soften some of its harder elements, there are no desperate bids for pity. There are also no neat or trite endings; this isn’t a triumphant memoir and is all the truer for it.

*

‘Original Sins’ is out now and available here (£15.79).

Ali Millar is the author of ‘The Last Days’ — a chronicle of her upbringing in, and escape from, the Jehovah’s Witnesses. Published later this month by Ebury, it is our Book of the Month for July.

Ali reads from ‘The Last Days’ as part of our lineup for this year’s Camp Good Life festival.