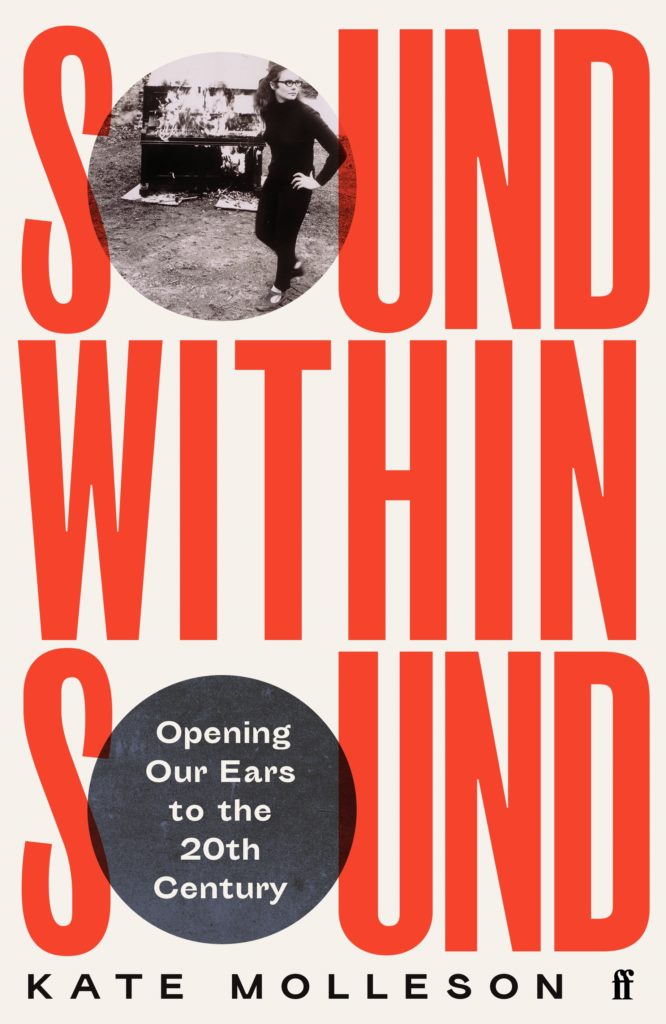

Newly published by Faber, Kate Molleson’s ‘Sound Within Sound: Opening Our Ears To The Twentieth Century’ reaches towards a more expansive definition of classical music, writes Andy Childs.

Kate Molleson is a distinguished teacher, journalist and broadcaster whose New Music Show on Radio 3 is a crucial component of that station’s gradual and, some may say, long overdue policy of embracing a more inclusive, global concept of what could be termed modern classical music. Think jazz, electronic music, improvisational music, folk, classical, experimental, noise, and combinations thereof. Molleson is a passionate advocate for this more expansive definition of classical music and, as this important and engrossing book establishes, she is particularly engaged in extolling the work and telling the stories of the many composers from around the world whose music has been side-lined, undervalued and ommitted from the mainstream histories. Of the ten composers whose work is discussed here, all were born in the first four decades of the twentieth century and seven are no longer with us. Because their work was adventurous, rule-breaking, often extreme and because they weren’t either white, male, privileged, European, American or born in the right place at the right time, they have never been fully accepted as part of the mainstream narrative of contemporary classical music. As such, this is not only an important book but an ear-opener, a revelation and a portal to another world. A world in which music has an anarchic, organic quality that defies categorization, where music has no boundaries and restrictions, stylistically and geographically, both in form and execution, where innovation and complexity and rigorous musical disciplines work together to stretch and embellish our understanding of what music can be.

Molleson has employed her expert knowledge and refined perspective in selecting which ten artists to include in what, in less discerning hands, could have been an unwieldy, daunting tome. She has chosen ‘ten beautifully messy, confounding, brave, outrageous, original and charismatic composers’. Each one of these elegantly written biographical essays describes a remarkable, singular, creative life, strewn with political, social and domestic obstacles. They describe a fierce commitment to their art, a refusal to compromise and a determination to write whatever music they pleased. They are wonderful characters, if apparently not all easy people to get along with.

The first chapter features ‘violinist, composer, instrument inventor and unbiddable polemicist’ Julián Carrillo (1875-1965), a Mexican, who in 1923 published a theory that he said ‘would uproot and seismically revolutionise the entire musical world’ and which aligned him with other avant-garde composers around the world who felt constrained by the rules of traditional composition. Modesty and fear of contradiction did not in any way inhibit his ambitions, even though his ideas often seemed fluid and vague. Such was his commitment to realise his musical ideas that he invented and built special instruments in order to express his music accurately — fifteen microtonal pianos, a ‘weird string bass contraption called the octavino’, microtonal oboes and harps. Molleson sums up her feelings for him deftly when she says ‘he was surely obnoxious, but I hold my hands up and admit I am charmed by the zany audacity of Carillo’s vision’. Likewise Brazilian Walter Smetak (1913-84), ‘gruff underground innovator and unlikely occult godfather of Tropicalia’, sound sculptor, author and playright, who invented and built 176 instruments of his own (including his collective flute — five metres long, made of bamboo and can be played by twenty-two people at the same time), recorded with Carmen Miranda and had his first album produced by Gilberto Gil and Caetano Veloso. Russian Galina Ustvolskaya (1919-2006) was another uncompromising individual — pupil of Shostakovich — who searched for ‘new ways of embodying terror in her music’ but whose later work nevertheless exhibited a spiritual quality. And she loathed any attempt to analyse her music. Like many of the composers in the book she was restless, contradictory, single-minded and formidable.

Despite her compositions being distinctly uncomfortable I think I might have actually enjoyed the company of Ruth Crawford Seeger (1901-53). Molleson does the next best thing when, in one of the book’s most engaging chapters, she interviews Ruth’s daughter, the folk music legend Peggy Seeger, at her home in Oxford. I too have spent time with Peggy Seeger and if her mother was anything like her she would have been politely intense, single-minded but warm, charming and funny. Quite difficult to reconcile this and her family’s profound association with folk music with Ruth’s challenging, dissonant, avant-garde music. Molleson describes her as ‘wholesome, meticulous…never swore, who crocheted on the porch and read Perry Mason detective novels’, but she was also ‘a sensationally skilled composer…a pioneer of hard-hitting modernism…she composed caustic little piano pieces, blindsidingly intense songs…hers was unapologetic music that blazed a trail for a new national paradigm — or might have done, had she kept going with it’. Trouble was, domesticity, family life and a subservient marriage to a man — her teacher and a composer not nearly as gifted as her — took over and her career and influence in the world of contemporary experimental music waned. She kept composing well after her star had faded but Molleson and Peggy Seeger quite properly lament the lot of creative, talented women in a rigidly uncompromising patriarchal society.

If Ruth Crawford Seeger is our connection to the world of folk music, then the other American profiled in the book, Muhal Richard Abrams (1930-2017) is a link to jazz. Raised in the South Side of Chicago, the young Abrams absorbed the music of Dinah Washington, Nat King Cole, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf and Sun Ra. He wrote ‘fearsomely exploratory orchestral works, chamber works, electronic and piano works…constantly reinventing his sound’. He was a maverick, unclassifiable but renowned in the jazz world; his story and influence is remarkably far-reaching and worthy of a separate book.

Other chapters here feature José Maceda (1917-2004), a Filipino composer, pianist and ethnomusicologist whose astoundingly ambitious works, performed on a massive scale, were coerced by Imelda Marcos who ‘had a taste for lavish cultural and infrastructure projects’; the splendidly-named Ethiopian pianist Emahoy Tsegué-Mariam Guèbru (b. 1923), influenced by jazz but had a unique compositional voice; Else Marie Pade (1924-2016) — a pioneer in Danish electronic music; Éliane Radigue (b. 1932), a French composer whose music ‘sits at the remote margins of form, sound and silence’, and worked with drones, tape loops and synthesizers and sought to ‘repurpose sound and the way we hear it’. And lastly we read about the startling Annea Lockwood (b. 1939), a new Zealander, re-settled in the UK, who incorporated the gentle sounds of nature in her work but also indulged in ‘instrumenticide’ — abusing and destroying instruments (mainly pianos I believe) to hear what that sounded like. She even played at the ‘hippie haven’ Middle Earth club in 1968 where she apparently smashed a variety of glass in a creative fashion. Molleson notes that ‘her glass concerts gathered a cult following. The likes of Pink Floyd’s Richard Wright, Soft Machine’s Kevin Ayers and composer Michael Nyman counted themselves as devotees’.

This is but the sketchiest outline of oustanding lives that Molleson brings to the fore so vividly. Not all of the music that she talks about is easily available to listen to but there is a fairly decent range of material on Spotify to accompany the reading and give you some idea of what these remarkable characters achieved. She portrays a world of exceptional compositional talent that, had it been given rightful prominence, would have enriched and expanded the domain of modern classical music beyond measure. And I would assume that it’s by no means just an historical problem although thankfully, these days, we have scholars and broadcasters like Molleson to continue the work of redressing the balance. Moved more to centre-stage instead of consigned to the margins, who knows what amazing music might develop? Radio Three should give her her own weekly show in which to feature the lives and work of these marginalised and fascinating composers. It might not always make for easy listening but, as she so clearly argues, their story and their work deserve to be heard and integrated into a long-overdue revisionist appraisal of the music of our time.

I can think of no better way to end than to quote from Molleson’s introduction, an introduction that will surely persuade you to read the book if I haven’t managed to: ‘These composers aren’t alternatives to any others, because the word ‘alternative’ suggests an incontrovertible core. They seek to replace nobody, but they deserve to be heard. And this is only the beginning. There are hundreds of others I could have written about. Seek them out, too, just as soon as you’ve finished reading.’

*

‘Sound Within Sound’ is out now and available here (£17.65).