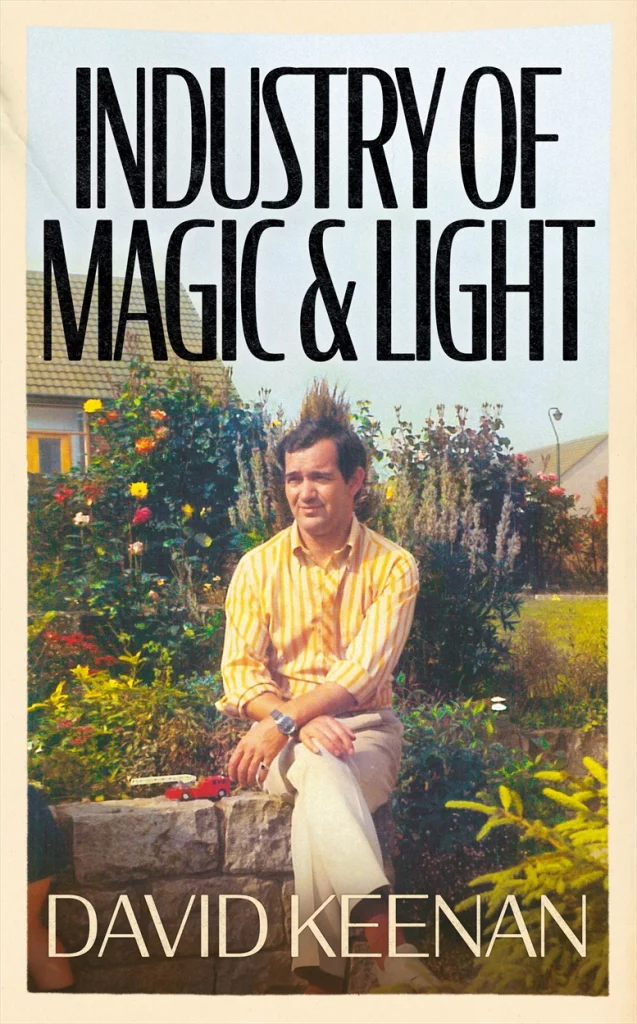

Published today by White Rabbit Books, David Keenan’s ‘Industry of Magic & Light’ — the prequel to his cult classic debut ‘This is Memorial Device’ — is simultaneously a forensics of the 1960s, a detective novel, an occult thriller, a vision quest, and the hallucinatory exposition of a moment where it felt like anything was possible. The power of art radiates throughout, writes Darran Anderson; to make life liveable, to make the dead-ends interesting, to make the ordinary epic.

In the summer of 1873, Paul Verlaine was walking home from the market in Camden. He was carrying a fish and a bottle of oil to feed himself and his partner, fellow poet and émigré, Arthur Rimbaud. Almost at the door, he looked up and noticed Rimbaud was gazing down from their window, laughing at him. Climbing the stairs to their flat, Verlaine was greeted with words to the effect of, “If you only knew how much of a jerk you look carrying that fish.” It was the final straw in what had been a tempestuous affair. Verlaine left on the next ship to Belgium. When they met again in Brussels, Verlaine was drunk and manic and brandishing a revolver. After threatening suicide, he shot Rimbaud in the wrist. Verlaine would leave for jail, while Rimbaud, barely out of his teens, would leave Europe and poetry entirely, though not before completing an epic he’d been working on that whole wretched year. As with all Rimbaud’s writing, A Season in Hell still astonishes. It is an openhearted yet mysterious exploration of the self and a searing bonfire of the vanities. It was an evolution of his earlier claim that would cast a spell over many people in many artforms and disciplines in the years that followed, ‘Je est un autre.’ I is an other.

We live in very different times of course to Victorian cursed poets, but certain qualities have only grown wider and deeper since then. One is a phenomenon the novelist Gabriel García Márquez called the ‘three lives’. There is the public self, exhibited to others, the private self, exhibited to ourselves, and the secret self, which we dare not display or examine, or may not even consciously be aware of. Each one unlocks potential wonders and horrors. The theatre of the public self can lead to inspiration and stature in art, fashion, politics yet equally it can lead to delusion and deception. The private self can be a refuge, hermitage or prison. The secret self is where the greatest perils and treasures lie. When the nexus between these lives begins to warp, when they drift apart or one comes to dominate at the expense of the others, dysfunction arises. For all the creativity that the performance of self-invention brings, it is mirrored in the fear of the doppelgänger, those strange doubles who wander the streets wearing our clothes, who inhabit other people’s perspectives of us, who hide in our attics and basements. Where the true self exists is questionable. Perhaps it lies in the things we never intend anyone to find, not the public memoir or the private diary but the discarded junk.

Somewhere in the North Lanarkshire village of Greengairs, there is an abandoned caravan that contains a universe, or at least its wreckage. The first half of Industry of Magic & Light rifles through the contents, an archive of a lost countercultural scene in 1960s and ‘70s Airdrie. A prequel to This is Memorial Device’s post-punk labyrinth, the book blurs the lines between fact and fiction, knowing that the border is always a peculiar, contested and unstable territory. Just as the Surrealists cultivated the transitional hypnagogic state between sleep and waking for inspiration, the earthy realism of Industry of Magic & Light lends weight to David Keenan’s wild inventiveness. Equally the imaginative passages add a curious ‘parallel world seeping into ours’ feel to the text. Keenan has managed to successfully summon an imaginary yet completely credible and immersive cultural scene from his head and into the streets of his youth, achieving for a second time what I’d long thought impossible.

“If you remember the Sixties, you weren’t there” goes the cliche. And sure enough, Keenan, born in 1971, remembers them vividly. Industry of Magic & Light are the recollections of one who was not there through the discarded relics of those who were, and it is nothing less than a triumph, building up a complex portrait of Central Belt psychedelia. As the author puts it, ‘Back then there was basically an annexe of Woodstock down behind the garages.’ The Flammarion engraving re-enacted twelve miles east of Glasgow. Weird scenes inside the Monklands.

It is told, at first, through bricolage; fragments of found texts, esoterica, objects, like an epistolary or decadent novel of old but one electrically and lysergically charged. It must be said that it’s not an accumulation in the pointillist sense, to reveal a broader singular vision; the purpose and power of Industry of Magic & Light is that it retains its enigmas regardless of its streetwise honesty, which is regularly hilarious and occasionally disturbing (the recurring radio snippet of a boxing match gone wrong for instance). As his earlier books show, Keenan writes beyond the contrivance of resolution. Life doesn’t work that way, nor should fiction always be compelled to. He does many mercurial things you would be taught not to do on most creative writing courses. He disrupts as well as balances. The results are thrilling, mostly due to the mesmerism of the voice and pacing, his eye for compelling details and dramas that steal upon the reader, and his egalitarian capacity for introducing us to real and imagined oddities.

Throughout Industry of Magic & Light, from Alice Coltrane to Rainer Maria Rilke, the power of art radiates; to make life liveable, to make the dead-ends interesting, to make the ordinary epic, or as epic as it actually is (we’re on a rock spinning through space after all). It is a testament not just to art but boredom, and the lengths to which it can drive its sufferers. “Freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose” Kris Kristofferson once sang, but it’s often forgotten that’s only the beginning. It gets bleak or it gets strange, by necessity, after that. There are ‘Happenings in the fields and quarries that surround Airdrie… broadcast through a handmade PA stolen from a bingo hall in Coatdyke’ and illuminated by hallucinatory effects produced by an overhead projector marked ‘Property of Airdrie Academy’. Though fiction, Keenan writes of a deeper truth here, for in the forgotten corners of countless towns, uncanonised by commerce or celebrity, people had read the likes of Yukio Mishima and listened to songs like Hendrix’s ‘1983… (A Merman I Should Turn to Be)’ and strange happenings had actually begun to occur.

Absurdity is never far away in Industry of Magic & Light. The human propensity for derangement and disaster, heartbreak and decay is constant. Yet life is stranger than it seems, and other possibilities inevitably exist, if not in this world than another. From Bazooka Joe wrappers to empty bird cages, Silver Surfer comics to a lost detective novel, the discoveries that make up the chapters are not meticulously studied and contextualised in the History of [insert place] in 100 Objects sense. Instead, they are either deadpan asides or cascades of freewheeling prose, or both at the same time such as the cave guru vignette. Even though it is set in the past, Industry of Magic & Light has nothing static about it, other than the caravan of its setting. It is a book in motion, with each find setting off a movie reel, until all these odd yet familiar films are playing simultaneously which, for all Keenan’s satyr experimentalism, is closer to life than the lie of the straight narrative. It is lifelike in the way you don’t get to choose what stays with you after reading. People come and go, entering and leaving, until life seems less like a series of happenings and more like a series of vanishings.

The second half of Industry of Magic & Light is drawn from a deck of tarot cards, harking back to Keenan’s splendid collaboration To Run Wild In It with the artist Sophy Hollington. Tarot has a number of fascinating qualities in its application here; how it relates to the voices and accounts; questions of irony, determinism and hidden intentions; how retrospective stories are told via a predictive medium; Tarot as a tool of lateral thinking; the possibility of uncovering or concealing what is already there; the role of the esoteric not in revealing a hidden world but the secret self. The pace quickens and, with it, paranoia, violence, collapses and erasures. A line from another song comes right back around to haunt the era, ‘Something is happening and you don’t know what it is…’

At the heart of tarot is interpretation. Perhaps a portrait can be constructed not just from things left behind but by examining the value someone places in them. In his exploration of the values of the discarded, whether objects, place or people, David Keenan reveals himself to be one of the most generous and ingenious writers of our times. This is a book that looks inwards as an intimately local collection of stories but also bursts outwards as an ever-expanding map, a sun collapsing under its own gravity. Industry of Magic and Light is the latest in Keenan’s line of substance-restoring and gravity-defying books. They are visionary not just in their weirdness and propulsion but because of their view of the ordinary, as something anything but, and their belief in possibility. ‘Can you imagine an equivalent moment of cultural trust and gravity today?’ he asks, and through the existence and sheer exuberance of this book, in the face of fashionable pessimism and cultural inertia, the answer might just be yes. Reading Industry of Magic & Light, you are reminded extraordinary ground-breaking works of art can come from the unlikeliest places, they nearly always do, because you are holding one of them in your hands.

*

‘Industry of Magic & Light’ is out now. Buy a copy here (£18.03).

Darran Anderson is the author of ‘Inventory’, which has been shortlisted for the PEN Ackerley Prize, and ‘Imaginary Cities’, chosen as a best book of 2015 by the Financial Times, The Guardian, the A.V. Club, and others. Visit his website here.