Will Ashon’s latest book — a portrait of contemporary Britain told through the testimonies of its inhabitants — affirms how odd and eccentric random and anonymous strangers are, and how there’s no such thing as the Average Joe, writes Michael Smith.

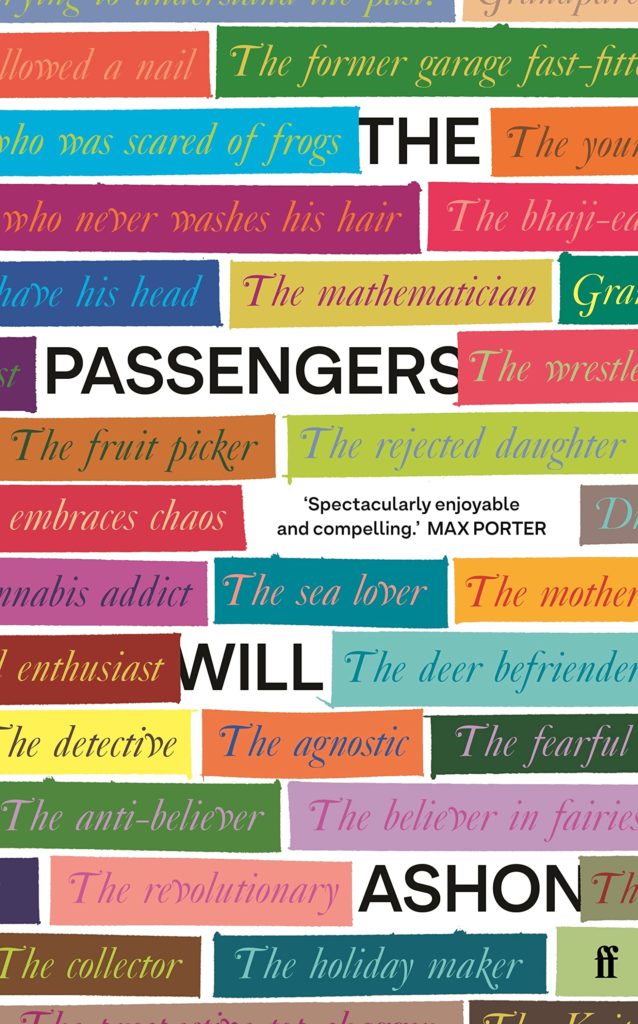

When the good folks at Caught by the River sent me the new book by novelist Will Ashon in the post, I automatically made certain assumptions as I unpacked and examined it. It’s a beautiful literary object: the tactile, textured paper the colour of bone, paragraphs floating upon it spaciously, in that impeccably tasteful and timeless Faber house typeface, that iconic ff logo with its all its classy, discreet historical weight. I once got a glimpse into the poetry editor’s office at Faber, all aesthete’s austerity, almost a monk’s cell, and on the bare white wall above the old wooden desk hung TS Eliot’s old editing scissors he used to manually cut’n’paste WH Auden and Sylvia Plath’s poems with — huge, heavy iron things, like something you’d use to shear a sheep. That ff logo comes with a whole load of weighty expectations. You don’t get much more trad or literary a literary publishing house. Everything about this book authoritatively affirmed the idea of “literature”.

What a pleasant surprise, then, to find a book at right angles to all that. The Passengers is not a work of fiction, but something far more original and interesting. I’m only half-sure it’s a work of literature. It’s free of all that baggage. It has the feel of a contemporary art piece that has assumed the literary form. An as-yet undefined, emerging 21st century form in 20th century clothing.

Will is more the curator than the author of this book. He employed various techniques to gather the material — letters sent to random addresses, conversations while hitch-hiking, asking random people online to tell him a secret or to choose an option from a list; strategies which seem designed to to short-circuit the authorial impulse to cast the world in his own image, and also to allow himself to break out of his own echo chamber, and arrive at something truly random, to get at a genuinely objective cross section, in order to take a valid psychic weather forecast of this polarised country at the current moment.

It kept reminding me of those Martin Parr videos, when BBC2 let him loose with a video camera and he roamed the country making five-minute shorts out of random encounters with the people he met, asking them about the meaning of life in the England they found themselves navigating at the turn of the millennium. There’s a similar subversion of the medium going on here, a trojan horse into something more abstract and original.

A bit like that series of video shorts, The Passengers affirms how odd and eccentric random and anonymous strangers are, how there’s no such thing as the Average Joe. The Clapham Omnibus is revealed to be a tapestry of weirdness and curiously home-made ideas and outlooks that are usually kept private. “The bald head is pretty similar to a skull. You might say it’s a memento mori,” says a bald man who confesses he dreams of himself still having hair. These strange homegrown theories are cause for hope if you find yourself increasingly despairing of the perception management utilised by X-factor, the Murdoch empire or the Brexit Referendum to evil ends. “In Britain that’s what we live in isn’t it? Like being bystanders in a slow motion car-crash. We’re standing there in a mix of horror and glee. It feels like we’re in this perfect stasis, where acting feels completely futile. And futility feels normal. It’s this continuous extinguishing of hope by bombarding people with information.” With this all-too-familiar sinking feeling in mind, this peek into random people’s thoughts about how the world works comes as a relief, shows England’s collective psychic life as something far more heterogenous and stubbornly home-made and resilient.

“We used to say that when we look at somebody, to imagine it’s a chest of drawers. What’s on the top – you know, the vases or whatever you have on the top – is what you see immediately. That’s how you present to the world and how people see you. Then there’s what’s in the top drawer, and then as you get to know someone a bit more, you might learn what’s in the second drawer. Then of course we used to all have a laugh about what’s under the rug and the floorboards at the bottom, that nobody knows about.” The selection of vignettes in The Passengers straddles the whole chest of drawers, from the humorous to the harrowing, the trivial to the transcendent. One man starts, “I have a pathological aversion to hairdressers,” and ends, “If a bird shat in my hair, I’d probably jut wash it. Actually I wouldn’t, you wouldn’t need to, I’d just rinse it out.” Then you come across a pretty disturbing story about how bad Covid can get, a kind of borderline psychosis — “I felt like I’d been invaded by evil spirits…I felt my body wasn’t my own. It’s like your personality is being squashed and this thing’s taking over.” And then you find a woman talking about her first-hand experience of God and a union with the divine: “The way I would summarise grace is that there is a sense of being cradled by something that’s so pure and so light and so knowledgeable and so dependable that the weight of the world falls away, and all that’s left is you and that. That’s how I woulds describe grace.”

“2020, what’ve we had? We’ve had coronavirus, bush fires, we’ve had aliens, we’ve had war, we’ve had locusts…it’s all just disaster. A single loop of endless apocalypse.” It seems to me this book has come at the right time, a cause for cautious optimism, an odd, illuminating work, as eccentric and as random as its cast of anonymous characters — stubborn, home-schooled, homegrown humanity, in all its awkward eccentricity, like a Facebook feed abducted and appropriated for literary, artistic means rather than for more corporate or otherwise nefarious interests. More of these please!

*

Published by Faber, ‘The Passengers’ is out now.