In their respective new and imminent books, Eoghan Daltun and Guy Shrubsole make the case for the preservation of Britain and Ireland’s small remaining areas of temperate rainforest. Róisín Á Costello delves into the ghosts and lichen.

In 2017 I discovered a narrow strip of forest tucked under an escarpment near my parents’ home. The canopy was low, a woven thicket of hazel and ash and hawthorn. The light that filtered through the leaves was vermillion, bouncing off trunks and rocks bearded with lichen and ferns. Beside the ruins of a church hidden by the trees, small jewelled raspberries grew on bushes that clustered around a shallow limestone well, and fat, frosted sloe berries weighed down the branches of blackthorn trees. The air was soupy and my feet sank into hummus-rich soil. Guy Shrubsole, in The Lost Rainforests of Britain, describes visiting these types of forest as ‘like going into a cathedral’ as sunlight streams through ‘the stained-glass windows of translucent leaves.’ The scrap I found is one of the few remaining areas of temperate rainforest which cling on in isolated pockets of Britain and Ireland, and which form the subject matter of Shrubsole’s forthcoming book, as well as the recent memoir by Irish writer and farmer Eoghan Daltun.

Temperate rainforests exist in areas where it is wet and mild enough for plants to grow on other plants. ‘Wet enough’ means areas that experience more than 1,400mm rain annually — a classification that captures some 11 million acres of Britain and a considerable portion of Ireland’s western coasts. And yet, as both Shrubsole and Daltun write, temperate rainforests are rarer than their Amazonian counterparts — covering just 1% of the world’s surface. We are, the authors remind us, citizens of rainforest nations. But we also inheritors of a landscape emptied of these miraculous groves where ‘trees [are] so heavy with lichen they look like they are bearded in tinsel.’

Shrubsole’s interest in Britain’s rainforests was sparked by his move to Devon and his discovery, or perhaps rediscovery, of Dartmoor — and Wistman’s Wood in particular. Like so many of the landscapes Shrubsole visits the Wood survives unmapped, both observable and unremarked — forgotten in plain sight. Daltun’s journey is perhaps more personal still, sparked by his desire to return the woods around his farmhouse in County Cork to their natural state, and to farm them in a way that preserves, rather than erases, the land’s character.

Both Daltun and Shrubsole read the ghosts of the rainforests they want to revive in the species that remain strewn across the landscape, and recover the collective memories of a woodland past that still echo in place names and myth. In Cork, the land where Daltun lives, Bofickil, was named by an English map-maker who attempted to reduce the Irish Badh Fiadh-Choile (the recess of the wild wood) to neat, English letters. Nearby, the townland of Faunkill derives its name from Fan-Choill (the sloping wood). In the common place names of Ireland, most of which were fixed by the eighth century, Daltun finds vanished oak woods and ash forests echoing off modern tongues.

Similar patterns of memory lead Shrubsole on his journey as he traces the wildwoods of Britain through the stories of The Mabinogion and into the maps of history, re-populating bare hills with the trees that once covered them. The name of Dartmoor itself is derived of the Brythonic Celtic for oak, derw. Elsewhere place names like Birch Tor, Hawthorn Clitter, River Okement, Watern Oke reveal landscapes that have faded from memory but still live in ink.

Shrubsole’s descriptions of the rainforests he visits are as precise, and as elegant, as the frilled lichens he delights in. To read the descriptions of his trespass into the rainforest at Holne Chase is to step into a Jurassic world of enormous ferns, dripping canopies and mist drenched rockfaces. Yet for all that the book is poetic in places, it is also political. Both Shrubsole and Daltun write about spectral landscapes, but telling the stories of how these forests became ‘ghost woods’ requires both authors to confront the forces that caused their disappearance.

Both authors find their answers in a model of Empire that stripped resources from the territories it controlled to fuel its own expansion, cut down forests to civilise the land and those who used its wild recesses for shelter and (after the enclosures of the eighteenth century) enriched its upper classes by privatising the raw materials of timber and land. Echoes of the forces that drove this stripping of the landscape endure in some respects. Both writers find that the drive for financial return keeps land empty of the trees it could support, while in England many of the remaining rainforests are on private land — at once preserved by the fences that contain them, and vulnerable to the whims of those on whose land they are located.

The authors diverge in their outlook on how we treat, and should treat, the land today. Shrubsole’s book is a political call to rewild the landscape. And yet, rewilding itself poses a threat when pursued too vigorously. Shrubsole acknowledges that rewilding has the potential to become a new kind of colonialism — removing the way of life, and means of living, of rural communities. In Wales, where farming has sustained a vibrant Welsh-speaking population, there is resistance to movements which might threaten erasure ‘scavenging a future from the ruins of a culture.’

It is in understanding the complexities of these dynamics and the individual needs of farmers that Daltun’s book shines. His writing is quieter than Shrubsole’s but it is deeply personal. An Irish Atlantic Rainforest is full of conversations between farmers and neighbours as they lean over walls, fences, and kitchen tables. These conversations are not only about nature and how to save it but also about how to live; not in abstract terms but in hard, practical ones. Daltun recounts carrying a yew on his shoulders down a mountain, and negotiating with neighbours over deer exclusion fences that may infringe their views. He is familiar with the worry of money running thin in the seasonal business of farming — and how many other jobs must be worked outside a farm to keep it going. His caretaking of his own small chunk of rainforest is told in these terms. There is delight and wonder in his account but there is also the pragmatic acceptance that to make others feel the same way, they must have the safety of knowing that the survival of a forest does not come at their expense.

There is a haunting passage in Daltun’s book in which he reflects on the nineteenth century population collapse on the peninsula where he lives that likely allowed his rainforest to avoid destruction. Recounting the number of deaths — of famine or disease — during the 1840s and 1850s, and reflecting on the scattered ruins of a small village in his forest, Daltun concludes that, in some ways, the landscape he cares for is a post-apocalyptic one. A place full of ghosts that, for once, are not trees.

Both books in the end turn on questions of survival — of ecosystems, but also of ways of life. The answer to these questions is political, as Shrubsole argues, but it is also personal. The world we live in is made and remade over boundary walls and kitchen tables more often than in halls of power.

*

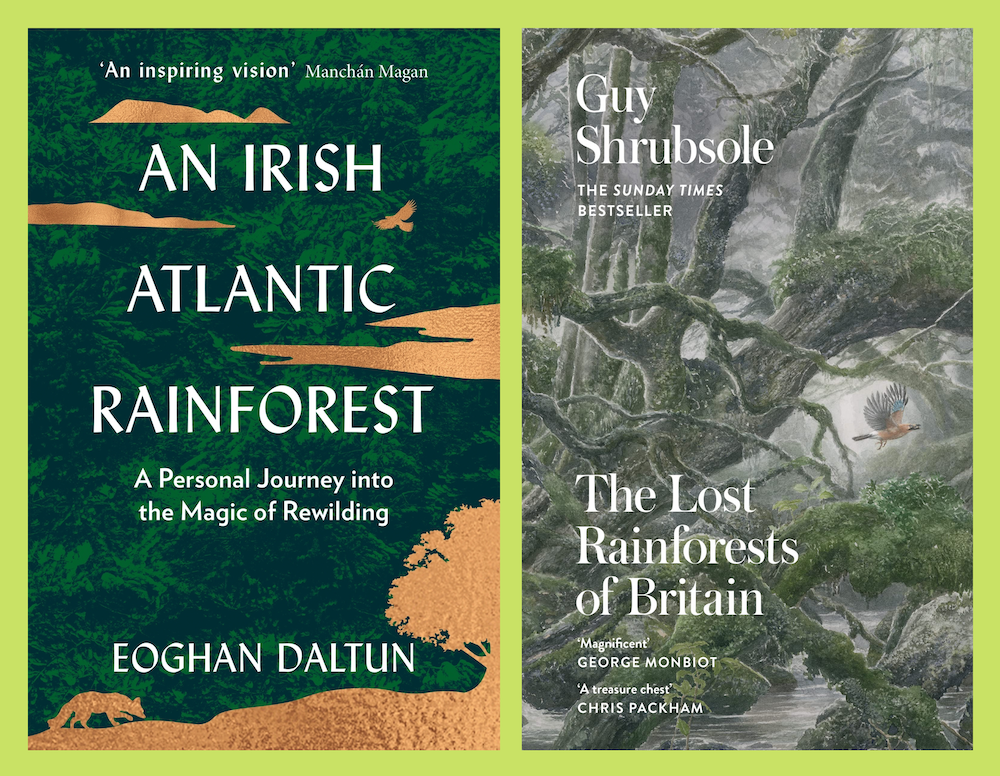

Eoghan Daltun’s, ‘An Irish Atlantic Rainforest’, published by Hachette Ireland, is out now and available here (£16.13).

Guy Shrubsole’s ‘The Lost Rainforests of Britain’ is published by William Collins in October. Pre-order a copy here (£19.00).

Róisín Á Costello is a bilingual writer and academic who lives and works between Dublin and County Clare, Ireland. Her writing has been published in Elsewhere and The Hopper, and in the Spring 2022 issue of Banshee. Róisín has previously been shortlisted for the Bodley Head/Financial Times essay competition and in 2021 was selected as the recipient of a Words Ireland mentorship by Dublin City Council.