Armed with her tent, her thumb, and a rendez-vous with a sailboat captain, Sarah Thomas heads to the Westfjords of Iceland; the landscape that birthed her book ‘The Raven’s Nest’.

If a place gives itself to me, long and deep enough to make work with it, it is only right to give something in return.

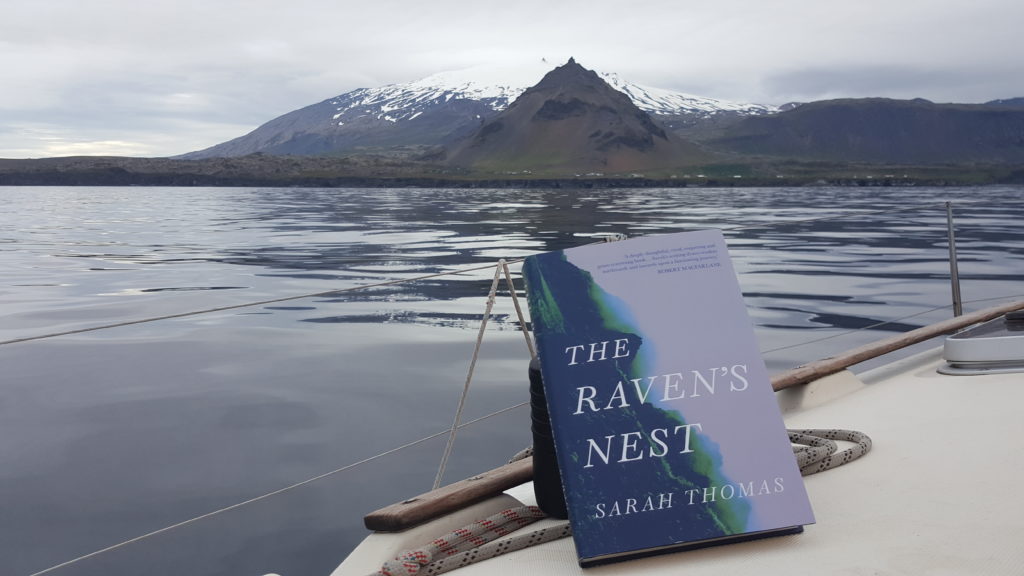

My ecological memoir The Raven’s Nest, recently published by Atlantic Books, is set in Iceland’s Westfjords, where I spent six years living, loving, learning and letting go following the financial crisis of 2008. I knew wanted to be there on publication day, a place where the book would not be so much a ‘new release’ as a basket of shared stories, ideas, and memories to gather around. I wanted to be reading it aloud to the people and places that are in it, in those places. Icelandic summer is the only time for open air roaming, a fullness of days. And so I went, with my tent, my thumb, a rendez-vous with a sailboat captain and a box of books sent ahead.

The journey to the first of five public readings I did in Iceland over two weeks this summer, was made by sea: the ‘whale road’.

*

“There’s some whales if you want to see them.”

An understated and well-timed wake-up call from the captain, as I give up trying to sleep over the engine noise, turned on to get us on our way, the sail ineffective on this calm day. I emerge from the darkness of my tiny cabin into the generous light of a July horizon steaming with spouts of spray; curved backs breaching and vanishing in a slick of black; birds circling overhead. Humpbacks probably. It is an auspicious start to a book tour.

We pass a lone fisherman, and wave. Curious fulmars occasionally pull up alongside us, and we cross paths with puffins and guillemots floating in the blue. Following this concentration of life, we see nothing for hours.

“The sea can be like a desert, for miles” the captain says. “And then… an oasis.”

Much as The Raven’s Nest is about chance and living well with uncertainty, it is a matter of chance that I find myself here, now, in this way. Iceland taught me a lot about that. I met the captain in the Faroe Islands in 2015 — me attempting to hitchhike to Iceland, he bailing from his voyage from Norway due to fierce weather and unable to offer a lift, both finding ourselves invited into the belly of the Faroese schooner Norðlýsið, to partake of its infamous hospitality. Thanks to that chance encounter, I have become honorary occasional ‘crew’ (aka the cook) on his own small boat in Iceland, that lift deferred and made many. When I make my almost annual migration, I usually make part of my journey with his boat and motley crew for a day or a few, wherever it is.

This trip began with my most direct route to the sea yet: within a ten-minute taxi ride from the airport, I was aboard. The captain’s destination this time is Breiðafjörður (‘wide fjord’), a bay of thousands of tiny islands between Snæfellness and the Westfjords where I once lived. Flatey, 2.5km long and 1.7km wide and the only island inhabited year-round, is where I will do my first reading. The harbour near the airport was on his route. I arrived at 2am to a pier devoid of people, the world asleep, the boats overlooked by a wooden hut from which the sound of amplified snoring was emanating, embodying the sentiment of the hour. The captain told me it is an ode to a troll woman featured in a historic series of children’s books by Herdis Egilsdóttir. Though her snoring was clearly noteworthy, she was mostly celebrated for coming to the rescue of fishermen in a storm.

Now we’re heading north across Faxaflói, the vast bay which is embraced by Reykjanes (‘smoky peninsula’) to the south and Snæfellsnes (‘peninsula of the snow mountain’) to the north, with Reykjavík (‘smoky bay’) tucked in its shelter. The place-naming settlers would find that the ‘smoke’ was in fact geothermal steam exhaled by an earth where magma is never far from the surface, which has recently erupted once again, not far from our point of departure.

Being early July – close to midsummer – it is never dark, and our movements are determined entirely by the weather. We cross the ‘desert’ making a course towards Snæfellsjökull, that iconic glacier-capped mountain, supposed portal on Jules Verne’s Journey to the Centre of the Earth. Today it is unusually crisp in its detail, clear of cloud. We anchor under the mountain floating in a silken sea, the light dissolving into sleep.

Hours later, the day before publication day, we are forced to duck into a harbour to wait out a 28-hour gale that was only forecast last night. Strong wind blows our boat away from the pier and mooring alone is a three person job. Finally, we hunker down, wires clanging on the mast, the fenders groaning against the hull. Journalists from the two national papers interview me over the phone – the howling wind louder than their questions. It takes me several hours and a change of mindset to find the sound relaxing. I brave the weather and go to the village pool where I meet the crew of a French sailboat heading for Greenland who are reconsidering their plans.

The storm past us, we set off again into dazzling sun and little wind, though remnants of the gale’s energy still pulses through the waves. Before we head for Flatey, we plan to explore an uninhabited island in the archipelago. En route the toilet breaks, so it’s overboard release for now; chats with curious fulmars who come to watch. In deeper water, we stop to fish. Cod after cod bites the line within seconds. I have only sea fished once before: this luck is not technique but a thrilling moment of abundance. None are especially small but we throw them back until I catch one big enough for dinner. With a few flicks of a knife the captain has produced two fillets and launches the remains overboard to an explosion of fulmars who have been patiently waiting. That evening we eat our cod anchored in the shelter of this horshoe-shaped island, a golden-glowed amphitheatre for the cry of kittiwake, guillemot; and come dusk, for a heated debate between two red-throated divers, which hangs in the cooling air.

Saturday’s task is to collect a new crew member from Stykkishólmur – a major harbour – and stock up on supplies; try and fail to fix the toilet; get a shower at the pool. I visit Roni Horn’s Library of Water – an art installation of columns of meltwater from 24 of Iceland’s glaciers, housed in the town’s former library up on the hill. You only find out once you are there that the ticket office is at the bottom of the hill. The woman there gives me a ‘ticket’ which is the door code; says she is coming to Flatey tomorrow and will come to my reading. The library overlooks the bay, and the islands are refracted in the transparent columns. All of the glaciers from which the ice was collected have since receded and one of them, Ok, has died. I am the only visitor. The heating is on high and I am still dressed for the sea: fleece-lined dungarees, a wool jumper and a waterproof jacket. I begin to sweat to the extent I want to rip off all my clothes. I head for the door and find it will not open. I am locked into a library of glacial melt. This feels like a metaphor beyond that which may have been intended by Horns. While a heat wave is crisping Europe and the UK it feels like a metaphor for 2022. With 1% phone battery left I manage to text the captain, who comes to release me.

When all is done it is evening and we have heard there is a gig on Flatey. From Stykkishólmur we make the short sail in cinematic light, the sun’s rays spotlighting some islands while others rest in deep blue shadow; the sea sparkling like hammered silver. At 9pm we anchor off Flatey, the sounds from the party mingling with the raucous cliff of seabirds.

A band, Ske, is playing at the old samkommahsið (‘coming together house’ – a village hall), now part of the island’s only hotel. We take the dinghy straight over – me clutching a change of clothes in a bag. I make a beeline for the toilets to peel out of my dungarees and wellies and into something more suitable, and sidle into the fray with a bottle of ice cold beer. Perhaps 60 people – young, old and everything in between – are packed into a room hot with dancing. After 5 days on sea this is a carnival of human life and colour. Ske’s Polka covers of pop songs are a hit, which have everyone bouncing and singing along tunefully. The crowd is mostly summerhouse owners and their guests. The houses have stayed in the same families for generations and their owners remain deeply connected to this place.

Ever more merry, we form a conga line which snakes out of the door and around the building. I spot my crew, still in their wellies and drinking beer outside, and break away from the line.

“You know that was the mayor of Reykjavik whose shoulders you were holding?” the new guy asks, clearly amused.

“I didn’t, no.”

Several here tonight are Reykjavík celebrities apparently, but I wouldn’t have guessed. That is how it is here.

In the morning we wake to find a huge National Geographic cruise ship has anchored the other side of the harbour. Tourists are ferried in rib boats to the shore. This is inconvenient for our back step toileting. We decide to bide our time a little and explore a nearby island with the dingy, before the captain leaves me on Flatey with my bag of everything, the tourists gone to their next stop.

At 2pm I find Gyða, the woman with whom I planned tonight’s 8pm reading. She tells me that the posters arrived but the books she ordered haven’t. In my experience, Icelanders deal with what is in front of them, so it was less strange for her than for me for this to have not been mentioned before now. So far she has only put one poster up – in the old cold store, the venue. She was waiting for me to actually arrive. Many things can happen, especially on an island, that change or delay plans – the changeable weather, ferry cancellations. This means advance planning is treated lightly. An intention is set and plans left flexible. Luckily this has given rise to a spontaneous mindset, which would serve us all well in these times of disruption.

Now I am definitely here. There are no books to sell, but a reading can happen. Now it is time to advertise, for an event in 6 hours’ time. Many from Saturday’s party have left back to Reykjavík so it’s only the summer dwellers left. In an hour I have put posters up at the hotel, knocked on every door, and Gyða has posted to the island Facebook group. Everyone will know and ten would be a crowd.

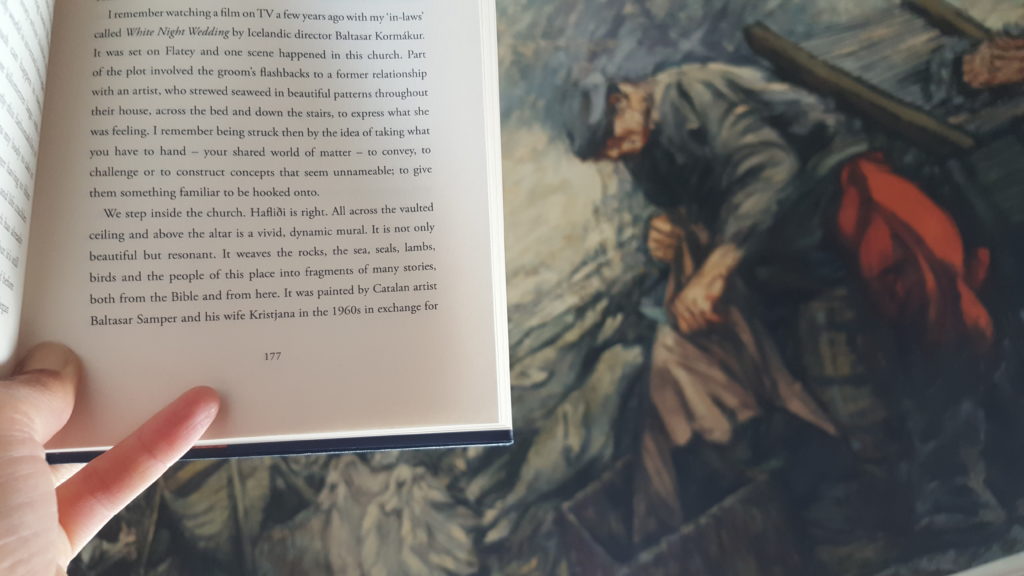

Finally, I can sit down for a coffee with Hrönn – one of the island’s two farmers, and my host. Hitchhiking as I am, I have planned my readings south to north. My first stop is Flatey because two of The Raven’s Nest’s central chapters are set here, in and around this house. They honour her now elderly parents Hafliði and Ólöf. This house is the first place I ever stayed on Flatey, back when they ran it as a guest house. In the intervening years I have often camped in their garden. Ólöf is now in an old people’s home in Stykkishólmur and Hafliði, once the man who always stood by the gangplank to greet ferry passengers and take news and goods, is now too old to do so.

Hrönn has taken on Hafliði’s role at the pier and has bought the house from her parents. She cannot be bothered with hosting tourists, but has invited me to stay inside because there are builders working in the garden. In the time period of the book, I didn’t know her at all. She is described only in a long shot as ‘a woman in bright orange rubber dungarees’ who I watched lift a seal from a fishing boat. Now I will get to spend time with her in close up. Hafliði comes in to join us. He is bright as a button but slow on his feet. I don’t know how we get to talking about it, but soon he is telling me about people with second sight, one of whom was islander Ingimundur Jónsson who died here in 1934. He knew of a boat of Flatey islanders drowning, long before the news reached the island.

The table is set for 8 and I ask Hrönn why. She tells me her father Hafliði lives with her, her niece is staying with her, I am here, and she is feeding the 3 builders 3 meals a day. They happen to be the husband and sons of Gyða, my event contact and a relative of Hrönn, so she most often joins them too. Dinner tonight is birched smoked lamb sausages and mash – lambs raised by her, meat smoked by her, potatoes grown by her. I am offered eider eggs, kittiwake eggs, rhubarb cake.

At 7.45pm I go down to the venue, the old cold store which now houses a volunteer-run café and shop selling coffee, hot dogs, handknitted mittens and jumpers, secondhand books about nature and the sea. The guests are gathering. Some I recognise from the party, some from my door-knocking, and Guðrún, the woman from the Library of Water has indeed come.

“You know I got locked in?” I tell her.

“Oh! That happened to a guy last week too! He climbed out of the window. It’s supposed to have been fixed but…clearly not.”

We gather round in mismatched armchairs and I tell them, to whoops of delight, that this is the first reading following publication day. Not in London, or Edinburgh, but Flatey. I tell them that though I got engaged here, and my marriage to my husband is long over, I remain married to this place. I read them the two chapters set here, about Hafliði and Ólöf. The quality of their listening is so tangible, I daren’t look up, or stop. At the end of those two chapters, we sit in silence for a while.

“It’s like music,” Guðrún says.

Another woman shares that the image of Hafliði at the pier brought a tear to her eye, as he is no longer there.

I ask if I’ve made any errors.

“There is one,” says Stína. “In 2011, Ólöf did not have hens. She had ducks.”

*

‘The Raven’s Nest’ is out now.

Through autumn and winter, as well as author Q&As, Sarah will be doing a series of extended readings inspired by the Icelandic tradition of ‘kvöldvaka’ (‘evening wake’), where as the nights drew in and the day’s work was done, the household would continue the work of knitting, darning and mending as one person read aloud to them from the light of a single oil lamp. Audiences are invited to bring their crafts and mending projects to do as she reads.

Outwith Books Glasgow 27th September

Tidespace Kirkcudbright Sunday 11th September

The Crannog Centre, Loch Tay Saturday 24th September

WayWord Festival, Aberdeen Sunday 25th September

Wigtown Book Festival Saturday 1st October

Lancaster Litfest Saturday 8th October

Stanfords Bristol Tuesday 11th October

Stanfords London Thursday 13th October

The Marlow Bookshop Monday 19th December

Keep an eye on her Twitter @journeysinbtwn for further details, or her events page.