In his latest book ‘Four Winters’, Jem Southam conjures magic from the light and the shadow, finds Alistair Fitchett.

‘In the middle of a December night a few years ago I was woken by the phone ringing downstairs. Nothing good ever comes of such a call and this time it was news that my younger brother had been admitted to hospital, and the doctor caring for him had rung to say he thought it unlikely he would live through the night. I drove to see him and sat with him through the early hours, in the eerie quiet of the emergency ward, until late in the morning when it appeared he would pull through.

When I got home that afternoon I decided to go for a walk by the river. As the dark of the dusk gradually gathered I sat on a log to sift through the thoughts and emotions of the day. Gradually I became absorbed in what was in front of me; the turbulence of the streams surface as the water raced around the bend, the waving of the reeds and the branches of the overhanging tree, and the pink of the clouds being pushed across the sky by a south-westerly breeze.

When mallard ducks pushed out from the bank to swim across the river in search of a safe haven for the night, I picked up the small digital camera I had just started to use and quickly took a picture.’

Jem Southam

There is something profoundly moving about experiencing art that is rooted in the landscapes one calls home. I felt it earlier this year when I read parts of Davina Quinlivan’s gorgeous Shalimar and I feel it again looking at the photographs collected in Jem Southam’s Four Winters. The photographs move me most, I think, because whilst I have sat on the same log, watched the waving of the same reeds, enjoyed the sight of the same mallard ducks and the same pink clouds, I have never made photographs that begin to approach the brilliance of Southam’s. Lord knows I have tried.

Some thirty years of teaching taught me that the easiest response to much art is “I could have done that”. This is especially true of photographs, and particularly so in an age when everyone thinks themselves a photographer just because they have a phone in their hand. The answer to such an assertion is, of course, “But you didn’t.” These are necessarily simplistic exchanges but they hint at the difficulty of being an artist, which is rooted in the not-so-simple act of the follow through. The challenge of actually Doing The Work. How many times have I thought of an idea and then watched it fizzle away like a damp squib on firework night? Far too many to count. Something always gets in the way. Often those somethings are pedestrian and/or irritating: Going out to work; cleaning the house; going to the store. Often too though those somethings are pleasurable: Going for a bike ride; swimming in the sea; walking on the cliffs; reading just one more book; listening to just one more new record; drinking a single malt as the sun goes down. Such things may be immensely life-affirming and enjoyable, yet they are not doing the drawing. They are not making the photograph and they are not rolling the ink and lifting the print. Life is a trade-off, and this is why I am not an Artist. Or a Cyclist. Or a Swimmer. Not really. Not even remotely. And this is why I could not make the photographs that Jem Southam has made. This is why Jem Southam is an Artist and I am not.

Something else I remember from early in my thirty years of teaching is spending hours watching the same Andy Goldsworthy documentary film over and over again with different classes. I was not, and am not still a huge Goldsworthy fan. His work does not seem to me to be as eloquent or elegant as Richard Long’s, for example, although I do understand why people are drawn to his sculptural interventions in the landscape. One thing I did like from that Goldsworthy film however was hearing him talk about spending time really getting to know a place. It sounds so easy yet is extraordinarily difficult to achieve with any depth of feeling.

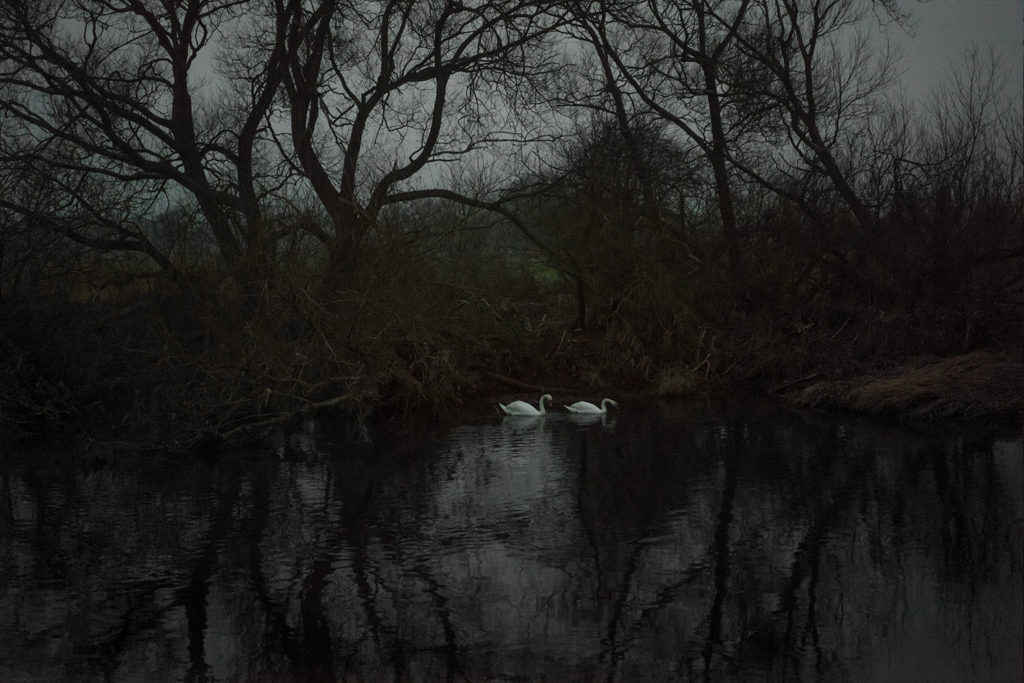

Jem Southam clearly knows this place on the river Exe. One of his previous books, The River: Winter explored a larger stretch of the Exe, going up as far as the bridge over troubled water at Bickleigh (yes, local legend still has it that Paul Simon was inspired to write the song after playing a show at the Fisherman’s Cot pub in 1965, even though Art Garfunkel punctured this myth back in 2003) whilst in his photographs of The Painter’s Pool he immersed himself in Stoke Woods, a hair’s breadth from the confluence of the Exe and the Culm. None of these photographs, however, fall into the well-worn trap wherein a single repeated source becomes a vehicle for exploring light, tone and ever-changing mood. They do this too, of course, yet for Southam the very essence of the place seems to be the subject as much as anything else conjured by the processes of photography itself. In these Four Winters photographs that place is very specific, with all of the pictures being made at dusk or dawn at just a few points along the river near the village of Brampford Speke. The first winter is photographed at a bend near Burrow Lane, whilst the subsequent three shift downstream to the fields below St Peter’s church before finally focusing on the flooded pond where Southam captures the river in spate reclaiming part of its passage from more than a century past. In the summer months Swallows will nest in the rich red banks and swoop across the river catching flies, but in Southam’s winters these banks are invisible below the waters and the swallows replaced by geese, ducks and swans. The brightness of summer too is replaced by the delicious cloak of winter, and many of the photographs are suffused with the softest light imaginable, like landscape viewed through what author Malcolm Saville would have described as being that gentle rain peculiar and particular to the West Country. They are painterly pictures, glowing with the illusory spectral resonance of Constable sketches. Much remains hidden. Human presence is suggested only by the lights of the cottage near Lake Bridge, glowing like a beacon of warmth in the winter’s morning or evening chill. Mostly though the human hand is shrouded, acknowledged only through contemplation and consideration: Southam’s presence behind the lens, making decisions about what we see and what we do not, feels essentially invisible, whilst the knowledge of the changes in the river’s course come only through immersion in aged maps and the gathering of ultimately useless trivia, like the shoes and plastic toys left discarded in the layers of mud and enmeshed twigs after the floods subside.

These photographs then, capturing as they do the passage of their titular four winters, are rich in meditative reflection and elegantly capture both the impermanence of life and the eternal cycle that nature perpetuates. The recurrence of swans in this place and in these photographs is emblematic of this cultural mythology of death and renewal, as though the migrating geese have brought ancient Scandinavian lore to this corner of a Devon waterway. As Southam himself notes in the short text that accompanies the photographs, according to such mythology, the swans carry ‘the souls of the dead across into the afterlife’ and are ‘depicted drawing the chariot carrying the sun across the sky, which after sunset descends into the underworld, reappearing in the morning to renew the daily cycle.’ In so doing, perhaps, they invest this place with a simultaneously earthly and otherworldly energy that Southam in turn transmutes into visual form. He crafts it from the light and the shadow and allows the actors on the stage to dance their beautiful ballet. Birds fly. The whispers of ghosts settle on bare branches and the touch of what God we harbour inside pours salve on our wounds. Magic in here.

*

‘Four Winters’ is out now, published by Stanley/Barker.

This piece was previously published by the International Times.