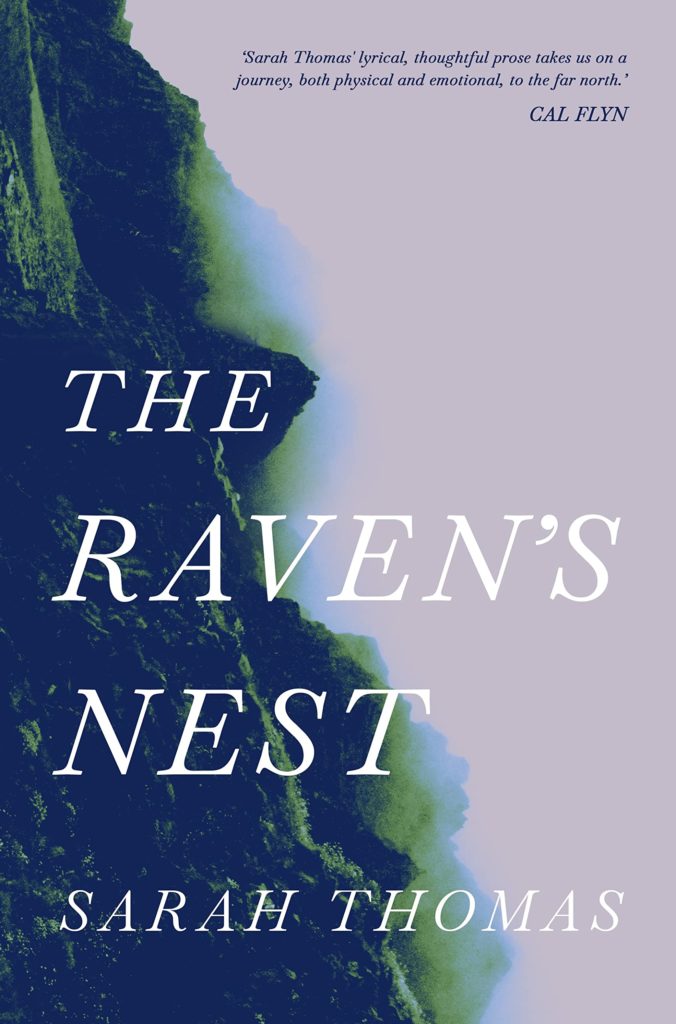

Centred around the act of homemaking in the Icelandic Westfjords, Sarah Thomas’ recent memoir ‘The Raven’s Nest’ shows our lives to be both huge and insignificant all at once, writes Amy Clarkson.

Through a repetition of tapping noises on the roof, a raven trains Thomas, the new human inhabitant of a hundred-year-old kit house, to continue the custom of leaving it offerings of bones and food scraps. This inherited ritual becomes part of Thomas’ endeavour of making home on the shores of Westfjords, Iceland — a landscape which reveals how the world itself is always in the making. Characterised by this close attentiveness to the more-than-human world, The Raven’s Nest shows our human habits of homemaking and belonging to be multi-agential, spanning across generations, and ceaselessly shifting in relation to biotic and abiotic influences.

Unfolding amongst multiple crises: the financial crash of 2008; a succession of volcanic eruptions and the intimately personal crisis of a marriage coming undone, The Raven’s Nest takes the form of thirty non-linear narrative essays, each intricately complicit to the meshwork of the whole. The dominating influence of light and dark shapes the temporalities of the book, moving as a force that not only obscures and illuminates Thomas’ experiencing of this sub-Arctic latitude, but as the architect of the societal interdependencies which shape Icelandic culture.

Thomas first arrives to Iceland to show a documentary in a film conference. Her life is startled into relation with this new place, and it unfolds like a love affair, in a series of encounters and synchronicities which are never as simple as settling. Flightpaths to Europe and Africa are made in relation with the volatile volcanic landscape to return again and again to this central holding place of Iceland. Her romantic involvement and then marriage to a local man, Bjarni, gives insight into the traditions of sheep-herding and fishing. On the cusp between insider and outsider, Thomas participates within the practices of this community, witnessing the specifics of a cultural lineage which prioritises human survival, and yet is bound within vulnerable, ever-changing ecosystems. The seasonal succession of wildflowers become annual markers of her evolving linguistic fluency in Icelandic, as the language grows directly from her lived experience of people and place.

Reading this as a narrative of the Anthropocene, the minutia and magnitude of the changing planet are embedded within Thomas’s close observations. Geological landscapes erupt through the narrative, with mountains and hot springs shaping the personal terrain. Working first in a campsite, Thomas’ positionality allows us to ponder what it means to be a tourist, to be visiting landscapes which are transforming, and undoubtedly susceptible to further exploitation, such as the new opportunities for cruise ships brought about by polar ice melt. The quartz beaches have been exploited for commercial means, and last season’s rubbish and dogshit are revealed by snowmelt. The repeated tic-tac patterning left by the walking poles give a visceral sense to the fragility of the thin layer of earth beneath, revealing an acknowledgement of the degradation of places that we visit.

Working later as a tour guide, Thomas holds the tourists in a narrative of her making, and we as readers are subject to the processes of careful concealment and curation of the landscape she cares about and sustains herself within. Questioning how to make livelihood in good relation, how to write about place in good relation, The Raven’s Nest creates intimacies with place, emotional landscapes and with the act of writing. Always relational, the memoir is a kind of call and response between personal and global. A glacier becomes extinct within the duration of this love affair, financial systems collapse, and we read this now within the context of a new cost-of-living crisis.

In the spirit of the Icelandic tradition of kvöldvaka, the readings which accompany the publication include an invitation to darn, knit or mend. At a reading given by Thomas in Glasgow, surrounded by an audience clutching yarns and needles, I came to appreciate the sparkling quality of orality layered within the text which makes the story land in the body, as well as the intellect. As I listened and darned, I realised that perhaps this is how a good story travels, through a casting that is both adaptive and regenerative, stitching places and lives into relation.

The Raven’s Nest affected me in a similar way to how a vast landscape can sometimes touch me. Showing how our lives are both huge and insignificant all at once. The narrative left me with a sense of permission to love, and to leave. Permission to return, in new relation. Permission to learn, and to be changed; to transform, and let go. Reminding me that through this epoch of climatic turbulence and planetary unravelling, our hearts will keep loving.

*

‘The Raven’s Nest’ is out now, published by Atlantic Books. Buy a copy here (£17.08).