As Saraband publish a new anthology of regional nature writing from the North of England, editor Karen Lloyd considers what levelling up might mean for inhabitants — and appreciators — of the natural world.

Gazing across Morecambe Bay towards the rolling hills of Furness and the Lake District mountains, I’m thinking about how the town of Morecambe itself is divided, one end a series of pleasant semis and detached houses and the other, one of the most socially and economically deprived areas in the country. As I write, an announcement is imminent on whether funding will be awarded for the proposed Eden North development, which, if it happens, will be a cluster of mussel-shell inspired domes adjacent to Morecambe’s iconic art-deco Midland Hotel. Eden North aims to re-imagine the town as a seaside resort for the 21st Century, engaging local communities through learning, employment and local supply chains, all this embedded within the central theme of fostering stronger connection with the natural world.

As a kid I didn’t know much, if anything, about the natural world. Like so many others, our family was in thrall to post Second World War aspiration, and I don’t need to rehearse here the consequences of all that. My folks regarded Morecambe as a second-rate Blackpool, which if your unit of measurement is based on the availability of seaside tat, was no doubt the case. From our Furness side of the bay Morecambe was visible across the sands as an exotic ribbon of white buildings. But for me its real allure lay in the chance to see the Guinness Clock, a phantasmagoric fusion of circus tent, clock-tower and castle with doors and windows that sprang into life every half hour, like a cuckoo clock on acid. Crowds assembled in anticipation, mums in pinch-waisted summer dresses and cardigans and dads somehow avoiding spontaneous combustion despite their fags being in such perpetual proximity to those profusely Brylcreemed quiffs, us kids hoisted on shoulders or gripping the railings.

At the allotted time the clock’s doors and windows opened to reveal a series of vignettes; a kangaroo keeping house, a gardener (weirdly) clipping a sea-lion (or was it a walrus?), a pair of pandas climbing poles and the next minute appearing from trapdoors on the roof. Behind one or more of those doors was an ostrich, and behind another a stork, though I can’t now recall what if anything they did. Us kids waited in feverish anticipation for the culmination — the chase in which the feckless zookeeper attempts to retrieve a bottle of Guinness from a joggling, mechanical procession of animals, a toucan, a sea-lion, a bear, the kangaroo. Back then, this was about as close as it came for me to wildlife. Wildlife was big animals, over there, in some massive foreign country even more exotic than Morecambe, and always only seen on the TV. Take the Saturday teatime Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau, with Jacques, his son Philippe and the crew of Calypso, those nattily attired knitted-red-hatted divers; those jolly bon viveurs. Oh Calypso! How I longed to swim with those green-backed turtles, the giant ray; the ocean churning with hammerhead shark!

So Morecambe Bay is not that, but much later I did come to know more about the wildlife of the bay, and even though the sands out there are treacherous, shifting, the bay is home to a fabulous number of birds, both migratory and resident, precisely because those same sands are jam-packed with food for all those different versions of what a bill is. But we know that the ground under all our feet is shifting under the twin tribulations of climate chaos and biodiversity loss. And those tiny aquatic organisms whose lives are lived in thrall to the tide — the shrimp, the mussels — are now found to be riddled with micro-plastics. I’m interested therefore, in what levelling up might mean for these inhabitants of the natural world.

Eden North’s central aim of fostering connection with the world around us is completely laudable, vital even. But I’m interested to know how we begin to build connections amongst communities whose kids arrive unfed at the local schools, something I’ve witnessed first-hand, and where the teachers told me their first job is to feed and keep feeding. This, because of the destructive shenanigans of the current procession of Prime Ministers whose life-experiences and motivations disregard entirely (in fact absolutely cannot know) what it means to live like this. So yes, levelling up; bring it on, but let’s be utterly realistic about the what and the how.

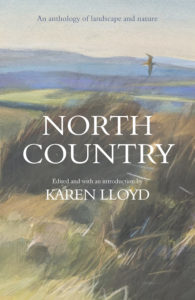

What’s all this got to do with a new anthology of regional literature, you ask? Well, I think there is a parallel, and it’s to do with how we writers choose to engage with the natural world. The ‘nature writing’ genre has, over recent decades, enacted its own form of shifting baseline syndrome. The term ‘nature writing’ itself is bandied about often through the expedient of marketing. It’s become something of a poisoned chalice; too wobbly and uncertain, often deploying nature as a backdrop against which human-centric recovery narratives play out. Given the state of the world, it’s also vital for writers to pay attention to the how and the why of nature, so when we began to plan the content for North Country, we needed not only to represent a broad geographic spread across the region and to include a fully diverse set of writers, but also to find writing that is a democratising force for landscape and nature — a kind of literary levelling up if you like — and that demonstrates epoch-appropriate ways of talking about the more-than-human world.

I think we’ve achieved this (though I would say that, wouldn’t I?) through the work of poets Zaffar Kunial, Lemn Sissay, Jane Burn and Helen Mort and through essays by Mark Cocker, Maxwell Ayamba and David Cooper. Sarah Hall is here too, which brings me full circle back to Morecambe and an extract from The Electric Michelangelo, Hall’s vibrant prose imagining the town pier engulfed in flames, and fire, of course, a natural phenomenon in its own right.

Another way of levelling up is to include the work of new and emerging writers, and here they come, these writers I’m sure we’ll be hearing more from. Take Jules Carter’s essay on Scafell Pike, about running and climbing, about the essay as form and about the mountains of litter left in the Lakes after the end of lockdown. Here too is Stephen Dunstan on the colliding worlds of football and birding and Jane Smith on toads and road crossings. Jane is the UK’s first town councillor elected on a platform of animal rights. She campaigns — successfully — on behalf of pollinators and animals, which in itself is another form of levelling up.

We may not be able to do much, if anything, to alleviate the complicated lives of some of our local communities, but we can pay attention well to the places we call home, and to some of the communities of the more-than-human world.

*

Edited by Karen Lloyd, ‘North Country: An Anthology of Landscape and Nature’ is just-published by Saraband. Buy a copy here (£14.24).

A book launch is being held at the Storey in Lancaster on Thursday 24th November, hosted by Lancaster University’s Future Places Centre. Book your place here. Further ‘North Country’ book events are to be announced throughout the region over the coming months.