Every year, we give over all of December (and usually most of January) to a series called ‘Shadows and Reflections’, in which our contributors share highs, lows and oddments from the past 12 months. Today it’s the turn of Alistair Fitchett.

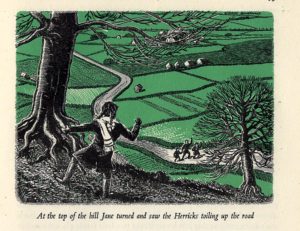

Illustration by Bernard Bowerman for ‘Jane’s Country Year’

The ongoing industry of cultural archaeology has this year thrown up many treats of literature, and the majority of what has thrilled me most is rooted in the period of the late 1940s and early 1950s. What strikes me about much of it, across several genres, is the way in which a remarkable maturity seems to settle in the pages. For writers like Margaret Kennedy, or Josephine Tey (both of whom I belatedly discovered this year), the contrast with their pre-WW2 work is startling and wholly welcome. In a contemporary era where reference to The Past seems increasingly weaponised in The Culture Wars, it can be paradoxically easy to underplay the immense shock imparted by WW2. Indeed, I read recently that in records of the UK Parliament debates, ‘blitz’ was referenced almost as many times in the period 2020-21 as in 1940-41, whilst the phrase “blitz spirit”, used just twice between 1945 and 2000 (in 1972 and 1999 respectively) has been summoned six times in the last 22 years. As Dan Hancox points out in his excellent article for the Guardian, it seems that ‘The further away we get from the Nazi blitzkrieg, the more we are asked to revive the “spirit” of the time.’

There is little of what we have been retrospectively encouraged to think of as “the spirit of the time” in any of the books I’ve read this year. Even in Margaret Kennedy’s wonderful Where Stands A Winged Sentry wartime memoir there is a marked lack of jingoistic patriotism. There is instead a poignant blend of obstinance and anxiety, as one might more realistically expect. In her magnificent novel The Feast (originally published in 1950 and set in 1947), Kennedy weaves some of the memoir themes into her fiction as she sets out a portrait of Britain teetering on the edge between those who might wish to cling to its (in)glorious Old Ways and those who look forward to a more equitable future. Kennedy is quite blatantly partisan about which of these she hopes will prevail and the ending of the book is quite remarkably brutal in many respects. It’s a stunning novel and is perhaps the single most enjoyed piece of fiction that I have read this year.

And then there is Malcolm Saville. Why did no-one ever tell me about Malcolm Saville? As a writer of children’s books, I accept that the context in which his name might have cropped up during my adult life would rarely, if ever, have arisen, yet I remain perplexed as to why it is only in 2022 that I have consciously stumbled on his work. Certainly it is possible that his books may have come into my orbit as a child and that I simply ignored them. I am rather resistant to such a notion, however, partly because it might illuminate how ignorant I was as a child, and partly too because I’m rather more certain it was to do with my growing up in Scotland. In the parlance of the geographical context of my childhood, then, Malcolm Saville is very certainly An English Thing. I strongly suspect that the librarians of my day would have turned their noses up and pointed mine towards Good Scottish Authors like Stevenson and Scott. Those elderly custodians of children’s texts of my youth would surely have glanced at Saville’s books, seen references to Sussex and Shropshire and then, tutting like Miss Jean Brodie, banished these wicked books with their English references to the murkiest corners of the building. This is wildly unkind of me, of course, but there we are.

It was actually via Margaret Kennedy that I stumbled on Malcolm Saville, and specifically her Where Stands A Winged Sentry memoir which was published by Handheld Press in 2021. An exploration of their other titles led me in turn to Inez Holden’s terrific collected Blitz Writing and then to Malcolm Saville’s Jane’s Country Year, delightfully illustrated by Bernard Bowerman. As an introduction to Saville’s work, I am now aware that this is a somewhat unorthodox entry point. Most would likely be more familiar with his extensive Lone Pine Club series, but I am rather pleased that I still have most of those to uncover in my future.

Jane’s Country Year then is structured, as the title suggests, in twelve chapters. Some Saville devotees have spread their (re)reading of the book across those twelve months and I admit that I am tempted to do the same in 2023. Although it was originally published in 1946, like many of the other immediate postwar pieces of fiction I’ve been reading this year, the war is barely acknowledged yet still casts a shadow over proceedings. So whilst in the book Jane in convalescing, it is difficult not to equate this with evacuation and thence to raise questions about the unapologetically positive light in which this enforced removal to the countryside is shown. We know that whilst for many children the experience of sudden urban to rural displacement was welcome, for many the experience was far from pleasant. Is Saville then guilty of retrospective propaganda? Perhaps. But it is difficult to maintain such thoughts when one is endlessly seduced by Saville’s obvious love of nature, landscape and rural folklore. So in March we learn that the budding leaves of the hawthorn were once called “bread and cheese”, though no-one seems quite sure why, or why bringing hawthorn and blackthorn into the house might be deemed unlucky. In June the scent of meadowsweet pervades the air and we see a kingfisher darting past with a silver fish in its beak, on its way to its nest of fishbones in the riverbank. In July Jane writes one of her letters to her parents and tells them of some plants she has found in the hedgerows: goosegrass and lady’s bedstraw. Perhaps understandably Jane fails to point out to her parents that goosegrass is also commonly known as sticky willy… In September Jane watches the fields being ploughed and Saville cannot resist suggesting that The Old Ways Were Best when he has the farmer remark that his tractor driving farmhand is ‘a good ploughman’ but ‘not as good as old George with his horses.’ Later in the month Jane experiences all the fun of the visiting Fair, whilst spiritual needs are met with the church’s harvest festival. Come November we are alerted to the presence in the hedgerows of the wild clematis known variously as ‘traveller’s joy’ and ‘old man’s beard’ whilst Jane spots some redwings feasting on scarlet haws. And so it goes.

Saville’s desire to share this infatuation is admirable and, for the most part, infectious. It doesn’t always succeed though, and the inclusion of the vicar’s son, Richard Herrick, as a means of imparting knowledge to Jane is, one might argue, rather clumsy and crude. He really is rather insufferable, as ‘clever’ boys of early adolescence are apt to be at any point in history, excitedly regurgitating facts and figures memorised from non-fiction tomes, Top Trumps playing cards, television documentaries or The Internet. It is tempting to see this as comedic to a degree, but a feminist reading of the text would no doubt pick up on this insistence on patriarchal power structures and point out that Jane is shown as being passively subservient. This may be so up to a point, yet Jane is also increasingly independent of action and thought as the year progresses, so it is tempting to read this as symbolic of ‘progress’ towards gender equality. As seen by a man, admittedly.

There is something in the book too about children’s displacement from parents, about the essential process of growing up and apart from those we share biological connections to. Jane’s parents and their urbane reactions to the countryside when they (rarely) visit their daughter may be stereotypical (mother is incapable of surrendering her dedication to City fashion and style; father is moderately more willing to enter into the spirit of the thing, which all does rather make one wonder whose side of the family this farming Aunt and Uncle come from) but then it does serve to remind us that Jane’s Country Year was written as a children’s book, and children do love a bit of stereotyping don’t they? (My tongue is firmly in my cheek as I write that).

If Margaret Kennedy is partisan in taking the side of modernity and hope for the future in The Feast then perhaps Jane’s Country Year is something of its counterbalance, with Malcolm Saville keen to make a fictionalised record of rural life and farming as it stared into the face of Progress, perhaps mourning that which he could see already changing irrevocably. Both as a book ‘about’ nature, farming and landscape, and ‘about’ childhood, Jane’s Country Year then is simultaneously explicitly and consciously of its time, yet also oddly, awkwardly timeless. I’m delighted to have read it this year and to have had the world of Malcolm Saville opened to me.